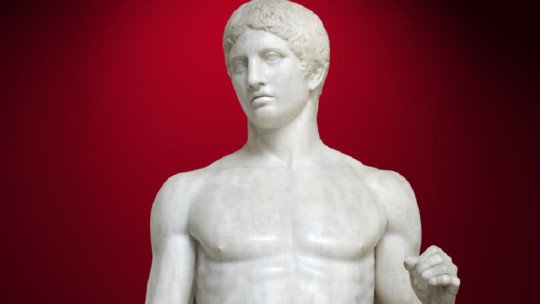

In 1908, an expedition led by archaeologists Josef Szombathy, Hugo Obermaier and Josef Bayer was excavating at Willendorf in lower Austria, very close to the Danube. One of the workers, J. Veran, made a singular find: a very small statuette, about 11 cm long and 5 cm wide, which represented a woman with prominent feminine attributes. She was baptized as Venus of Willendorfand its execution was dated to around 30,000 BC

What was the meaning of this statuette? What use had it had during the Paleolithic? Was it true, as early scientists assumed, that she represented the ideal of feminine beauty of the time? Or perhaps it was a representation of the Mother Goddess?

In this article we will try to unravel the mysteries of the Venus of Willendorf which, as you will see, are not few.

Characteristics of the Venus of Willendorf

Although the discovery was truly sensational, Willendorf was not the first Paleolithic Venus found in Europe In 1893, the team of archaeologist Édouard Piette found in Brassempouy, France, an interesting woman’s head carved in mammoth ivory and of tiny dimensions (3.65 x 2.2 cm).

Despite its smallness, the figurine presented exquisite delicacy: the features were clearly carved (except the mouth, which was non-existent) and it showed an elaborate hairstyle, the solution of which using grids made many specialists think that it was a hood.

The one in Willendorf, despite also being called Venus, has very different characteristics. For a start, He has no face: he only has a kind of hat (or what could also be a hairstyle, based on coiled braids) that covers almost the entire head. Furthermore, while Brassempouy’s Venus lacks a body, Willendorf’s shows voluminous forms, with bulging female attributes (vulva, breasts, hips).

The first scientists who studied these Venuses (and the many others that appeared throughout European geography, and that corresponded more or less to the same period) thought that the statuettes They could be capturing what in the Upper Paleolithic was the ideal of feminine beauty That is why they called all the figurines “Venus”, alluding to the goddess of beauty. However, throughout the 20th century this theory has been dismantled in favor of others that specialists have considered more plausible. Let’s see what it is.

The Great Primordial Goddess

The anatomy shown by these Venuses (mostly with very bulging genitals and breasts) has suggested the possibility that they were amulets that ensured fertility and abundance In fact, the small size of the statuettes shows their “movable” nature; They were undoubtedly made to be easily moved from one place to another.

Let us remember that the European populations of the Upper Paleolithic (that is, a period that spans from 40,000 to 10,000 BC) were nomadic. The fact that most Venuses (and Willendorf’s is no exception) lack feet reinforces this theory, since they have no support to stand on. Were they then worn around the neck?

On the other hand, the enormous presence of female figurines (more than a hundred have been found) could demonstrate the privileged situation that women would have in these groups of hunter-gatherers Following this theory, it would be quite likely that the woman was invested with an almost sacred character, as she was the repository of the miracle of life.

This would link, of course, with the theory of the Great Goddess, which maintains that, long before the arrival of the Indo-European peoples and their religion, there existed in Europe a current of worship of a Mother Goddess, at the same time giver and denier of life, responsible for birth and death. Then, the famous Venuses would be nothing more than representations of this Great Primal Goddess.

Amulets against death

However, new theories have recently emerged that are equally interesting and worth considering. This is the case of the study Upper Paleolithic Figurines Showing Women with Obesity may Represent Survival Symbols of Climatic Changefrom the University of Colorado, where the authors propose that, in reality, The overweight of the Venuses would, in reality, be a protection against famine and death

The theory makes sense if we take into consideration the period in which the figurines were carved, which coincides with the last Great Ice Age. The researchers realized that the body volume of prehistoric Venuses grew the closer they were to the glaciers or the closer in time they were to the great ice ages. All of this led them to think that, faced with the fear of dying of hunger, Paleolithic human beings began to value well-nourished bodies as a guarantee of group survival.

And it is not true that all the Venuses found present a large anatomical volume. According to Henri Delporte, The typology of Venus would change depending on the region in which they were found , which seems to fit more or less with the University of Colorado theory. Thus, for example, while the Venus of Willendorf has bulging breasts and hips, we have other examples such as the Venus of Mal’ta, in Russia, which do not present features of anatomical exaggeration.

A common culture?

Despite the differences described above, it is true that all European Venuses of the period show similar characteristics: they are representations of stereotypical women and are very small in size (none exceeds 25 cm). Thus, it can be stated that There was a fluid exchange between the human groups established in Europe during the Paleolithic

In fact, a recent study by an interdisciplinary team, made up of experts from the University of Vienna and the Natural History Museum of the same city, has shown that the material from which the Venus of Willendorf is made is not found anywhere close to where it was found.

The statuette was carved from oolite rock, a very porous material that makes modeling easier, and then polychromed with red ocher. However, the closest region where sites of this type are found is in northern Italy and, to a lesser extent, in Ukraine, which shows that the men and women of the Paleolithic were constantly moving.

If the Venus culture occurred throughout Europe, from the French Pyrenees to Siberia, the following information is very curious: There is no record of any Venus in the Iberian Peninsula which only increases the questions about the history and meaning of these prehistoric representations.