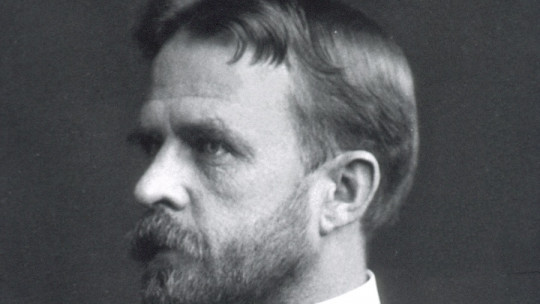

Thomas Hunt Morgan was a great man of science, whose research has been considered the fundamental pillar for the understanding of genetics as we understand it today, along with Gregor Mendel.

This American was an evolutionary biologist, embryologist, geneticist and author of several works who had the honor of receiving a Nobel Prize for his active scientific career. Let’s look deeper into his story through this brief biography of Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan Biography

Below we will look in depth at the life of Thomas Hunt Morgan, his relationship with various North American institutions and his position regarding the main evolutionary ideas of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Early years and training

Thomas Hunt Morgan was born on September 25, 1866 in Lexington, Kentucky. At the age of sixteen he attended the State College of Kentucky, now the University of that state. In that center he focused above all on science, especially natural history. During his summer vacation time, he dedicated himself to working for the United States Geological Survey.

He graduated in 1886 with the degree of Bachelor of Science. The following summer He attended the Marine Biology School in Annisquam, Massachusetts, where he became interested in zoology at John Hopkins University

After two years of working and publishing several publications, Morgan was chosen to receive a master’s degree in science from the State College of Kentucky in 1888. This same institution offered Morgan a job as a professor, although he ultimately chose to continue at John Hopkins.

It was at this time that finished his thesis on the embryology of sea spiders (Pycnogonida), to determine its phylogenetic relationship with other arthropods Based on their embryonic development, he established that they were more related to terrestrial spiders than to crustaceans. His publication was rewarded with the award of his doctorate in 1890. With the money he won as a prize for publishing the thesis, Morgan took the opportunity to travel through the Caribbean and Europe to continue his research in zoology.

Professional career and research

In 1890 Thomas H. Morgan He was hired as a professor in charge of morphology courses at Bryn Mawr School an institution twinned with John Hopkins University.

His work life at the institution was very intense. He gave talks five days a week, twice a day, mainly focused on biology in general terms. However, despite being a good teacher, he wanted to focus on research.

Stay in Europe

In 1894 he traveled to Naples to carry out research in the laboratories of the city’s Stazione Zoologica. There he completed a study on the embryology of ctenophores, an almost microscopic life form.

Being in Naples He had contact with German researchers, who taught him the ideas of the Entwicklungsmechanik school or mechanics of development. This school was reactionary to the ideas of naturphilosophie, which until then had been the reference in the science of morphology during the 19th century.

At that time there was a great debate about how embryos were formed. One of the most popular explanations was the mosaic theory which maintained that hereditary material was divided among embryonic cells, which were predestined to become specific parts of the organism once it was mature.

Others, such as Morgan at that time, thought that development was due to epigenetic factors, where interactions between the protoplasm and the nucleus of embryonic cells affected the way they developed.

When Morgan returned to Bryn Mawr in 1895 he was hired as a full-time teacher. There he addressed aspects such as larval development and regeneration in his research. It was also then that he wrote his first book The Development of the Frog’s Egg (1897).

Beginning of the 20th century, Morgan began researching sex determination a time in which Nettie Stevens, another great researcher, had discovered the impact of the Y chromosome in determining male sex in humans.

Columbia University

In 1904, Morgan was invited by E.B. Wilson to join Columbia University , where he could carry out his research work full time. A year earlier she had written Evolution and Adaptation, where he explained that, like other biologists of the time, he had found evidence of the biological evolution of species, but was not in favor of the Darwinian mechanism of natural selection. However, years later, after the rediscovery of the findings made by Gregor Mendel, Morgan would change his position.

Although he was initially skeptical about Mendelian laws, given that they were being given enough importance as a theory to explain Charles Darwin’s postulates, Morgan understood that they had a lot of sense and evidence behind them.

Studies with fruit flies

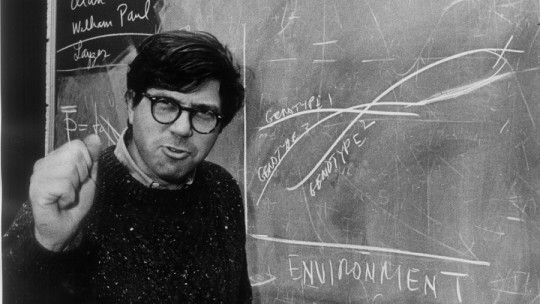

In 1908 Morgan began working with the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) He mutated, through the use of chemicals, physics and radiation, specimens of this very common fly.

He began crossing the specimens to find mutations that were heritable, but at first he did not achieve significant results. Additionally, he had some trouble detecting which mutations were actually hereditary. Subsequently, When he detected the mutations, he saw that they followed the laws proposed by Mendel

Morgan found a male fly with white eyes that stood out among its red-eyed counterparts. When white-eyed flies mixed with red ones, their offspring had red eyes. However, when the second generation, that is, the daughter flies, was crossed, white-eyed flies emerged between them.

Based on his research with flies, he published an article in 1911 in which he explained that some traits were inherited in a sex-linked manner, and that it was likely that the specific trait was stored in one of the sex chromosomes.

Based on these investigations, Morgan published in 1915, together with other prestigious scientists of the time, the book The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity , which is considered the fundamental book to understand genetics. After studies with the insect, Morgan returned to the field of embryology, in addition to addressing the heritability of genes in other species.

In 1915 he was critical of a new movement that had emerged from science, eugenics, especially when it defended racist ideas.

Last years

Several years later, in 1928, Thomas Hunt Morgan moved to California to take charge of the biology section of the California Institute of Technology (CALTECH). Over there He researched embryology, biophysics, biochemistry, genetics, evolution and physiology He would work at CALTECH until 1942, when he would retire and become professor emeritus. However, even in retirement, he would dedicate himself to continuing research in sexual differentiation, regeneration and embryology.

Finally, Thomas Hunt Morgan would die on December 4, 1945 at the age of 79 after suffering a heart attack.

evolutionary stance

Morgan was interested in evolution throughout his life Already as a young man he wrote his famous thesis on the phylogeny of sea spiders, in addition to writing up to four books in which he explained his position regarding Darwinian and Lamarckist evolutionary ideas.

in his book Evolution and Adaptation (1903) is critical of Charles Darwin’s postulates. According to Morgan, selection could never produce an entirely new species solely by acting on merely perceptible differences between individuals He also rejected the idea of acquired characters postulated by Neolamarckism.

It must be said that Morgan was not a scientist who went against the grain. In fact, the years between 1875 and 1925 are known as ‘the eclipse of Darwinism’, since the scientific advances of the time, together with changes in positions within the natural sciences, caused some of Darwin’s original ideas to fall apart. .

However, after his studies with Drosophila melanogaster, Morgan changed his position. Mutations are important for evolution , since it is those characteristics that are inherited that significantly affect the anatomical and behavioral changes of the species. These characters are inherited often following the laws proposed by Mendel.

Honors

Among the distinctions that Thomas Hunt Morgan obtained, we find the following:

Additionally, several institutions have been founded in his name, such as the Thomas Hunt Morgan School of Biological Sciences at the University of Kentucky. Also, the American Genetics Society annually awards the Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal to members of the institution who have contributed to the field.