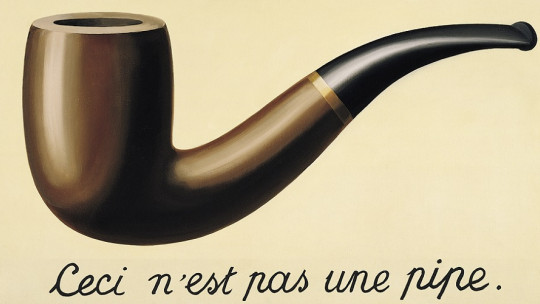

To start talking about the differences between crafts and art, we must ask ourselves, first, what era we are talking about. Because, although it may seem surprising, what we consider art today was not always considered art, and what we currently consider as such was not always treated as craftsmanship.

So, How to distinguish between crafts and art? What parameters can we apply when distinguishing between both concepts? And, most importantly, is it possible to distinguish them?

Differences between crafts and art: the fine line between two concepts

The Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy defines art as a manifestation of human activity through which what is real or imagined is interpreted If we take the definition of craftsmanship given by the same dictionary, we find that, according to the RAE, it is the art or work produced by artisans. From these definitions, we extract two ideas.

The first is that, in both words, we find the same root, art, which in turn comes from the Latin ars, a term with a plurality of meaning, since it can refer to art according to the concept that we have, but also to a talent or a ability; These last two ideas are also found in artisanal work.

In second place, The definition given by the RAE of craftsmanship includes the word art, as it refers to it as the art of artisans Both concepts, therefore, are irremediably linked. So what are the differences?

Artists were also craftsmen

The concept that we have of art and of artists as genius creators of subjectivity is, in reality, very modern In fact, although the idea arose in the Renaissance, in many places it did not fully take hold until well into the 18th century, thanks to the academies.

In the Middle Ages, what we call artists were mere craftsmen. There was no difference between a shoe maker, a basket maker and a painter. They were all included in the large group of manual jobs, that is, those that were done with the hands and (in principle) not with the intellect.

This type of occupation, vile jobs, were typical of the lower classes of the strict social hierarchy. It was unthinkable that the privileged, that is, the nobility and the clergy, would dedicate themselves to this type of work and, in fact, there were many members of the down-to-earth aristocracy who preferred to live financially tight rather than go to work in some vile job.

Perhaps the only exception was the copyists and illuminators of manuscripts, usually monks and nuns who belonged, de facto, to the privileged status. Their obviously manual activity (they used pigments and brushes typical of painters to execute their work) was duly camouflaged as intellectuality so that it could be appropriately associated with their status. Thus, the miniaturists did not paint, they illuminated scholarly texts, written by wise figures of the past. Here we had the necessary intellectual justification so that it was not a vile job.

This is also why, In the first centuries of the Middle Ages, practically all the artists who signed their work were dedicated to illuminating manuscripts , a theoretically intellectual, non-manual trade. But what about the fresco painters, the sculptors, the goldsmiths? We do not have the signature of any of them, just as we do not have it of the shoemakers, the basket makers and the rope makers. In fact, very often, to cite the author of a medieval work, terms such as a work by the master of Cabestany are used, referring to the fact that, although we do not know his exact name, the similarity of techniques and aesthetics point to which was made by the same workshop.

A workshop work

We are going to take advantage of the fact that the concept of a workshop has appeared to point out an idea that we consider to be of utmost importance in this debate. And it is the idea of the artist as an individual entity. Again, this is a modern concept, the son of the academicism of the 18th century and, especially, the 19th.

Before the emergence of the concept of the artist as an intellectual creator (and even for many centuries after) works were born from workshops, not from individual brushes or chisels. All artists with a certain prestige had a group of assistants and apprentices who gave them support in the creation of the commissions Let us remember that, as artisans that they still were, their work method was very similar to that of an artisan workshop: a master who directed and taught all the apprentices under his charge.

This is how great geniuses like Leonardo or Michelangelo created, of course. We cannot imagine da Vinci alone in front of the canvas, working alone and feverishly until the work magically came to life before his eyes. No, that is the artist of the 19th century, the romantic artist, not the workshop artist of the Renaissance, son of medieval artist-craftsmen. In fact, this confusion resulting from concepts taken out of context has led to more than one misunderstanding.

For example, on the cartouche of the Mona Lisa preserved by the Louvre you can read that it is a work by Leonardo. However, his twin in the Prado Museum is classified as a workshop work. From Leonardo’s workshop, of course, but wasn’t the Louvre Mona Lisa also from his workshop?

We insist: Before the appearance of the tormented romantic artist, creator of the great artistic subjectivity, artists worked in workshops Of Rubens’ canvases, probably a few brush strokes are by Rubens, the sketch at most. The rest is the fruit of the hands of the dozens of assistants who worked for him.

So artist or craftsman?

We have commented that the concept of the artist as an intellectual creator begins in the Renaissance; specifically, with the publication of the treatise De pictura by León Battista Alberti (1404-1472), where the intellectualization of art is claimed. From then on, and unlike medieval times, the artist will be considered an intellectual worker, and not a mere craftsman

But we have already seen that, in practice, this is not exactly the case. Rubens and company had workshops, and they worked in them with apprentices, in the purest style of artisan guilds. On the other hand, it must be remembered that the concept of the artist as an intellectual did not spread with the same speed in all parts of Europe. In the 17th century, when the idea was more or less accepted in Italy, Velázquez was still struggling in Spain to have his work recognized as something more than mere craftsmanship.

It was necessary to clarify all the preceding points before attacking the question that is the basis of our article: what are the differences between crafts and art? Speaking from our current world, we could say that art is linked to intellectuality and social prestige Works of art are paid dearly in the market, and the names of the artists practically shake hands with the gods. On the other hand, artisanal objects, although they can arouse great admiration, do not possess the social glory that artistic works do.

We will give a clear example that will perfectly illustrate what we are saying. If a deliciously made shoe comes into our hands, but it comes from an artisan workshop whose name we don’t even know (and which, furthermore, has produced several shoes in one day) we would possibly talk about it in terms of craftsmanship. On the contrary, if what we receive is a shoe from one of the most famous brands in the world, it is most likely that we would not use the word craftsmanship to refer to it, but rather we would talk about a work of art.

Even though the footwear company in question also produces in series (and, what is certain, in much larger quantities than the workshop), the prestigious name will give us enough reasons not to call it craftsmanship.

Because, Is there any difference between an artisan who produces shoes in his modest workshop and a painter who executes his works in a studio? No, it’s only the prestige that counts. A shoe craftsman may put his whole soul into his creations, while the considered artist may simply be carrying out a commercial commission.

The prestige of the artist began to develop in the Renaissance, when art began to separate from craftsmanship. However, to a medieval man, the question at the head of our article would have been ridiculous.