The role of women in the French Revolution is not as well known as that of their peers. And yet, women represented a very important force in unleashing the Revolution and, later, in keeping it afloat. There were also many women who, at first, sympathized with the revolutionary cause, but who later denounced the blood that had been shed in their name.

In this article we are going to analyze what role women had in the French Revolution and we will briefly stop at the lives of some of these revolutionaries.

Women in the French Revolution

The feminine ideal of the French Revolution did not change much compared to that of previous centuries. Women continued to be excluded from all intellectual and political activity, and special emphasis was placed on the “republican” model of woman: a wife and mother dedicated to caring for her family; especially, of her male children, future and committed citizens.

However, during the revolutionary years, women constantly manifested themselves, whether through their pen or through blood and brute force Thus, the women of the town were the main champions of the protests demanding food, while the more educated women began to demand a series of political rights through pamphlets, books and speeches. Both of them had a very prominent role in the evolution of events, as we will see below.

Educated women are revolutionaries…

The role of women in the French Revolution can be traced back much earlier. During the first decades of the 18th century, the so-called salons began to proliferate in France, meetings of intellectuals that were usually held in the home of a distinguished lady. This lady encouraged meetings between philosophers, politicians and artists and, although it was quite common for the hostess not to participate in the gatherings (she simply listened discreetly, as if it were not with her), these meetings spurred her curiosity for knowledge. and knowledge. Many of them, like the famous Madame Pompadour, the official mistress of Louis XV, were true intellectuals and great patrons of the arts. These ladies were called salonnières

Thus, under the protection of the Enlightenment, women began to get involved in social issues. This is not to say, of course, that it was frowned upon for ladies to participate in debates, but times were certainly changing. Women were no longer content to stay at home in charge of household chores; They aspired to real equality with their peers, and that happened, of course, through intellectual and political activity. There were many women who worked hand in hand with their husbands, wrote their speeches and even retouched them, to infuse their texts with new, much more attractive ideas.

These first women carried out their work in the shadows, in hiding, we could say, as is the case of Madame Roland, who we will talk about in another section. But, even if it is from the shadows, the salonnières They had entered the wheel of social change. They were faithful readers of the Enlightenment, especially Rousseau and Voltaire, as well as classics such as Plutarch , and were completely imbued with their social and republican ideas. Therefore, when the winds of change begin to blow, many of these women enthusiastically throw themselves into building the Revolution.

…and those of the town, too

But if there was a group of women whose role had a direct and crucial influence on the events that triggered the Revolution, it was that of the women of the common people. His role in this event is such that They almost killed Queen Marie Antoinette several years before the guillotine did it as we will see in the next section.

In his essay Women of the Revolution, Jules Michelet says that “men have done the work of July 14; The men took the royal Bastille, the women conquered the royal power itself and deposited it in the hands of Paris, that is, of the Revolution.” Michelet is carried away by exaggeration, it is clear, but his words hide an indisputable reality: that it was women, and only women, those who dared to set off to the very palace of Versailles to demand that bread that never arrived. It was what was called “the October marches.”

“We don’t have bread.”

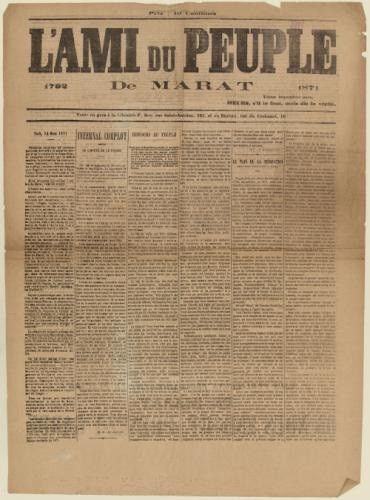

The autumn of 1789 was being especially harsh; cold and hunger loomed over France. On October 1, a banquet was held in Versailles in honor of the newly arrived guards, and rumors began to spread like wildfire. The news spread (on the other hand, never proven) that, during the banquet, the attendees had trampled on the newborn tricolor cockade , symbol of the Revolution, and had sworn allegiance to the white color of the Bourbons. This news, together with the very harsh conditions that the people of Paris were experiencing, who did not have a morsel of bread to put in their mouths, ignited the flame of protest. The incendiary denunciation of the banquet that the sinister Jean-Paul Marat launched from his newspaper L’ami du peuple (“The People’s Friend”) did not help cool things down.

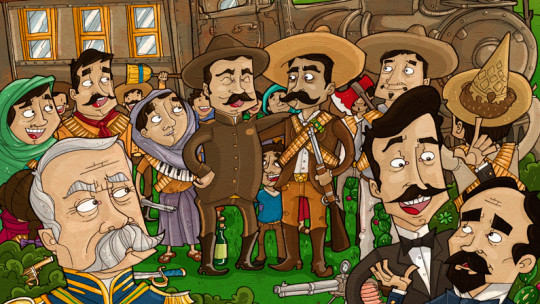

On October 5, in the afternoon, Some women from the central market gathered around a young woman who had taken a drum from a guardhouse and was playing generala It was the warning. In a few hours, a crowd of women from the surrounding markets had gathered; According to some authors, around 10,000 women could have gathered.

This torrent of hungry and excited saleswomen wanted bread, but, above all, they wanted “the baker,” as they called the king, to move to Paris, near their town. With these ideas, the women traveled the 25 km that separate the capital from Versailles in just six hours, under torrential rain and accompanied by the soldiers of La Fayette who, enthusiastically, had joined them on their trip. The women carried homemade weapons (knives, forks, mortars), but also real weapons that they had seized in their assault on the Paris City Hall.

After a long wait, as the king was hunting, a small group of women met him in his private chambers, and obtained from the monarch the promise of provisions and the signing of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. But, although the king believed he had satisfied the crowd, when night fell a large part of the women and soldiers were still there.

Around 6 in the morning, some of them managed to access the interior of the palace through a place that was not guarded ; Her goal was to go find the queen and kill her. Marie Antoinette was miraculously saved because, upon hearing the noises of the scuffle, she was able to run out of her room and reach the king’s bedroom in time.

That noon, the royal family left for Paris, just as the people had demanded. They would never set foot in Versailles again.

The women’s clubs

After the triumph of the Revolution in 1789, the will of women’s ability to actively participate in political and social changes was evident in the founding of countless women’s clubs Thus, in parallel to the famous men’s revolutionary clubs (such as the Club des Jacobins or the Club des Cordeliers), are inaugurated on Club des Replublicaines Révolutionnaires (the Club of the Revolutionary Republicans), the Club des Amazones Nationales (the National Amazon Club), or the famous Club des Amies de la Loifounded by the quarrelsome Théroigne de Méricourt, who is said to have actively participated in the October marches and who, later, confronted Robespierre himself.

These women’s clubs were associations of women from the popular classes, who met to read the daily newspapers, exchange opinions and debate. The male revolutionaries did not view the existence of these groups very favorably; In fact, on October 30, 1793, the Convention declared the closure of women’s clubs, arguing that their violence compromised the security of the Republic.

Were women’s clubs violent? Certainly many did, but they were no less so than those that were monopolized by men. Behind the decision to close them there was a much more ideological than practical reason: The Revolution granted freedoms, but not to women

The tricoteuses: the most violent face of the Women’s Revolution

Of all these revolutionaries, the most violent were undoubtedly the so-called tricoteuses, so nicknamed because they had the habit of knitting while attending the sessions of the Assembly. During the sessions, they constantly interrupted the deputies with their shouts, either asking for more severity or demanding the immediate death of a suspect. These women were also called Furies, since his position in the Revolution was the most radical; It is said that they even soaked their handkerchief in the blood of the beheaded.

The role of these tricoteuses was decisive during the so-called pradial insurrections (May 20, 1795). That day, a group of these women and a few sans-culottes stormed the Convention and demanded a tougher line against the suspects. When the deputy Féraud refused to listen to them, they did not hesitate to murder him and parade his head nailed to a pike throughout Paris.

Next to the tricoteuses There were the sans-culottes, men of the common people who formed the most radical wing of the popular revolution. They were called that because instead of wearing the typical culotte (that kind of tight pants that the nobles wore up to the knee, right where the stocking began to be seen) this social group wore long pants down to their feet.

Some of the women of the French Revolution

Here is a short list of 5 women who had a profound impact on the French Revolution.

1. Madame Roland

Born Marie-Jeanne Philipon into a more or less wealthy family, Madame Roland was a highly cultured woman who stood out for her wit and sensitivity. She and her husband, Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière, formed a highly esteemed intellectual couple in revolutionary society Although Madame Roland always tried to stay in the background, everyone knew that her husband’s speeches had previously passed through her hand. Her salon at the Hotel Britannique in Paris was very famous, and famous political figures, such as Robespierre himself, paraded through it.

At first she was enthusiastic about the outbreak of the Revolution, since she was a republican and a faithful follower of Rousseau. However, later, and deeply disappointed with the course of events, she and her husband denounced the numerous crimes that were being committed in the name of freedom. Madame Roland fell from grace and was guillotined in November 1793. Her husband, who had fled Paris, committed suicide upon hearing the news.

2. Olympe de Gouges

This is how Marie Gouze is known, an intrepid writer who has gone down in history for her Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens. Daughter of a bourgeois family, Olympe frequented the best salons of enlightened Paris; After becoming a widow, she began her literary career. The marked anti-slavery nature of her work did not allow it to premiere at the Comédie Française until the Revolution.

After the revolutionary outbreak, Olympe began a political activity that culminated with the writing of the aforementioned Declaration (1791), which intended to be a response to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizenwho had deliberately forgotten about women. The Olympe Declaration began with the famous phrase: “Man, are you capable of being just? A woman asks you this question…”

Aligned with the Girondins, the moderate branch of the Revolution, Olympe confronted Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety, which earned her a death sentence. The great feminist and abolitionist writer was guillotined on November 3, 1793.

3. Anne-Josèphe Theróigne de Mericourt

Coming from a humble Belgian family, in 1789 the young Anne-Josèphe found herself in Paris, in the middle of the revolutionary tide. It is not certain that she participated in the October marches, but we do know that was the founder of Club des Amies de la Loi one of the women’s associations so in vogue at the time, of which she was always a fervent defender as a vehicle of expression for women.

In May 1793, the tricoteuses stripped her naked to humiliate her and whipped her, in revenge for Théroigne’s adherence to the Girondist side. It is not known if it was because of this brutal attack or if the severe syphilis that she suffered from also played a role, but the fact is that Anne-Josèphe ended up losing her mind. She was admitted to several sanatoriums, a fact that, paradoxically, seems to have saved her from the guillotine.

4. Charlotte Corday

“The murderous angel,” the French poet Lamartine called her. And it is that Marie-Anne-Charlotte Corday has gone down in history as the murderer of Jean-Paul Marat the director of the most radical newspaper of the Revolution, The town’s friend.

Charlotte was a provincial girl, belonging to a family of the lower Norman nobility. A fervent republican and faithful follower of the Girondists, she was convinced that Marat was to blame for all the blood that was being spilled in France. Reason was not lacking, since, From his diary, the journalist demanded more and more heads

Determined to put an end to the problem, the young woman travels to Paris and delivers a fatal stab wound to Marat’s chest, in his own home, in the bathtub. The consequences of the murder were not what Charlotte expected; She was taken to the guillotine and, meanwhile, she was radicalized in Terror in France.

Nobles, bourgeois, saleswomen, intellectuals, weavers… The French Revolution is the great revolution of women. Because without them, the events probably would not have been what we now know. While it is true that their decisions and actions were not always the most moral and correct, the enormous role that women played in the French Revolution is indisputable.