Can we freely decide on our own actions? This question has been latent since humanity could be considered as such. Philosophers like Plato already explored these concepts centuries ago with the means at their disposal.

It seems like a simple question to answer, but it should not be so simple when it is an unknown that is latent in the entire legal structure that shapes modern societies. In order to decide whether someone is responsible for an action or not, the first thing that must be elucidated is whether he had the capacity to understand what he was doing and, then, whether he had the possibility of making a different decision. The principle of innocence derives from that precept. What seems to be clear is that it is not so easy to know the answer. Perhaps neuroscience can help us clarify this question a little.

Libet and his research on decisions

A few years ago, a researcher named Libet tested people’s ability to identify in real time the decision that has been made. His conclusions were clear; until almost a second before the subject became aware of his own decision, The researchers already knew what it was going to be based on the activity of its neurons.

However, Libet also discovered that, before executing the decision, there was a small period of time in which that action could be “vetoed”, that is, not be executed. Libet’s experiments have been expanded and refined by some of his disciples over the years, his findings having been repeatedly confirmed.

These discoveries shook the foundation of what until then was considered free will. If my brain is capable of making decisions before I myself am aware of them, how can I be responsible for anything I do?

The problem of free will

Let’s look a little closer at the neuroscience underlying this problem. Our brain is a machine evolutionarily selected to process information, make decisions based on it and act, as quickly as possible, efficiently and with the least possible consumption of resources. For this reason, the brain tends to automate the different responses it finds as much as it can.

From this point of view there would not seem to be free will and we would be more like an automaton; a very complex one, yes, but an automaton after all.

But, on the other hand, the brain is also an organ with the capacity to analyze and understand its own internal processes, which, in turn, would allow it to develop new mental processes that act on itself and modify the responses that it already had automated.

This approach would thus transfer the possibility of the existence of free will to the greater or lesser capacity we have to acquire knowledge of ourselves, and new habits capable of modifying our own responses. This approach, therefore, would open the door to the possible existence of free will.

The importance of self-knowledge

Here, the reflection that we would have to do then is: if we want to be more free and make better decisions, we should be able to start with “make the decision” to try to get to know each other better and, in this way, have the opportunity to develop new mental processes that act on our own mind and allow us to better manage our own responses. In a word, self-knowledge.

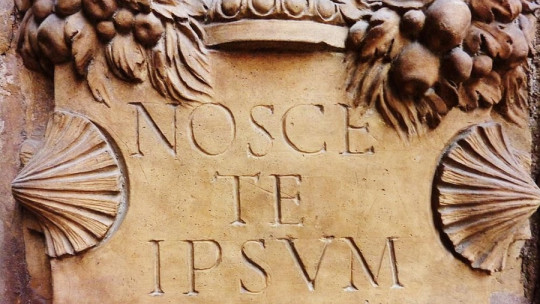

This is quite similar to the famous saying that crowned the entrance to the Temple of Delphi in Greece, “Nosce te ipsum”, or “know thyself” and you will know the world. True freedom is only achieved when we manage to free ourselves from ourselves.

But, giving a further twist to the subject… What depends on whether we decide to start the process of self-discovery? Does it depend on something external, like the opportunity for someone to make us think about it? And if that doesn’t happen… does our free will then depend on luck?

I think this is a good point to leave open for discussion and exploration in future articles.