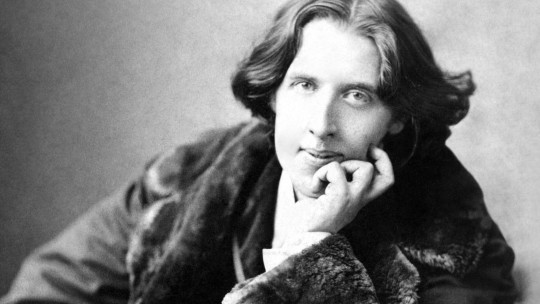

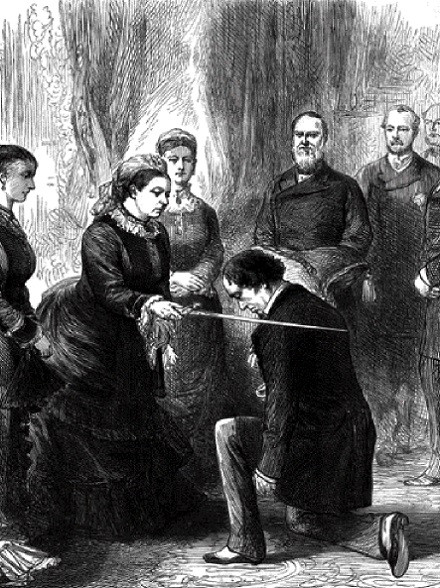

In 1837, Victoria I ascended the English throne. Her reign, in addition to being one of the longest in the country (only surpassed by that of Elizabeth II), gave its name to an entire period: the Victorian era.

What characterized this time? What did the famous Victorian morality consist of? Below, we offer you a summary of the characteristics of this period.

What is Victorian morality?

“Victorian morality” is known as the set of ideas and opinions regarding conduct and morality that prevailed in the United Kingdom during the 64 years of the reign of Queen Victoria I (1837-1901).

Some authors place the beginning a little earlier, with the reform act of 1832 (Reform Act 1832), which introduced very important changes in the English electoral system.

The queen has often been held responsible for the emergence of this new morality. And although, as we will see, its origins can be traced back several centuries, it is true that Victoria, and especially her husband Prince Albert, did much to exploit the image of the perfect family that was to be the pillar of English society

In general, Victorian morality was characterized by being very strict and having very rigid guidelines that dictated the behavior of citizens. For example, sexuality was an eminently taboo subject (despite the fact that London became one of the cities with the most brothels in Europe) and gender roles were rigorously constituted.

Although Victorian morality is limited to the reign of Victoria I, we find some antecedents in previous centuries, such as the rise of Puritanism in England and its particular “fight” with the more “flexible” ideological and behavioral currents. We see it below.

Background and context of Victorian morality

At the beginning of the 19th century, the United Kingdom is a nation in full expansion At the end of the 18th century, the so-called Industrial Revolution had begun, which had placed the country at the European economic forefront. The constant supply of raw materials from the increasingly numerous British colonies supported unprecedented industrial development, and the rapid development of railway infrastructure greatly facilitated their transfer and distribution.

The economic apogee inevitably led to a strong entrenchment of the values of individualism and work. Anyone who worked hard could become rich. There was no longer time for leisure and debauchery; Duty and sobriety emerged as the pillars of the new morality that would last for a century. Of course, and as we will see in more detail in another section, the weight of work and economic responsibility fell solely on the man the only one in charge of carrying such an “extraordinary” mission on his shoulders.

The foundations of this rigorous morality had been built two centuries earlier, when the English Puritan movement, led by Oliver Cromwell, confronted the monarchy. The Puritans intended to “purge” the Church of England of all Catholic residue, which they considered it had not yet completely gotten rid of. Rigid Puritan morals slowly seeped into English society and, although during the 18th century customs relaxed (probably influenced by the hedonism of the French court), in the 19th century these values re-emerged strongly.

“The Angel of the Home”

In this new Victorian society, The man stands as the pillar on which the family is supported At least, in economic terms. The man is the one who takes the reins of the business, the one who gets involved in politics, the one who speaks, the one who acts, the one who decides. All of this is a consequence of this new social notion, which separates the male and female spheres in a very pronounced and strict way.

Man’s terrain is business and politics. Men’s clubs proliferate, where men meet to smoke, play pool and discuss current affairs. Instead, The Victorian woman is relegated exclusively to the home environment

In effect, the only roles contemplated for women are the roles of wife and mother. She is what the poet Coventry Patmore called “the angel of the home”, the true definition of the Victorian woman. Within the very conservative society of the time, there is a belief that this is enough for a woman to feel full and satisfied. Or, at least, that’s what men think. Most women go with the flow, often afraid to stand out or protest, which would mean their social death. However, hTowards the end of the century, feminism and the demand for women’s rights gained strong momentum , especially the right to vote. What happened so that, in a society with such strict roles, women became aware of their situation and their rights?

Some authors maintain that women’s dedication to various charitable and social welfare tasks (the only ones that were considered suitable for them) led to a gradual awareness of their power and capacity. It must also be taken into account that, in the working classes, women worked the same as men. The factories were full of wives and mothers (and even girls, since child labor was rife) who worked from dawn to dusk to supplement the salaries of their colleagues. This, by necessity, had to influence the new feminine mentality.

To get a slight idea of what was considered “the ideal woman” in Victorian times, just read the statements made by the Reverend J. Goodby, from a parish in Leicestershire, regarding the death of his wife in 1840. From Mrs. Goodby He is said to have carried out his “duties” with mercy and patience “Duties,” of course, are restricted to caring for family and home.

A new fashion for a new morality

As we can see, the qualities that a Victorian “good woman” was supposed to have are highlighted in Mrs. Goodby. The morality of the time, strongly puritan, gave great value to qualities such as modesty, prudence and work, in both men and women.

This new frugal and modest morality is perfectly illustrated in the fashion that began to prevail after Victoria’s accession to the throne. The “standard” male suit was limited to pants, vest and frock coat, preferably in dark colors , in absolute contrast to the dandyism of the previous reign. No more strident colors, no more impossible combinations. A respectable man dresses modestly and modestly.

And if this was the case with men, what can we say about women’s fashion. Some fashion historians have called it “mousy fashion”, with some humor of course, but the truth is that they are right. Women moved from the extravagant and often outrageous fashion of the turn of the century to an extremely modest style of dress Even her bonnets lengthen her brims to hide part of her face, as if the Victorian woman felt ashamed of being seen outside her family sphere. Her colors, like her male namesakes, fade and darken.

A hypocritical society

As you might imagine, Victorian society displayed a delicate hypocrisy. Because while Christian virtues were praised, child exploitation was rampant in the United Kingdom. Working-class families often lived in a state of alarming poverty. The disease took its toll on a poorly nourished population, which lived overcrowded in the new neighborhoods born with industrialization. In London, the waters of the Thames were unhealthy: they stank and oozed toxic miasmas that facilitated the spread of evils such as cholera, which decimated the population. Infant mortality was very high, and few children exceeded the age of 5 years This chilling reality was portrayed by many authors, especially by Charles Dickens, the great chronicler of English Victorian society.

Likewise, while sex was censored in public, in private it was the driving force of an inhibited and obsessed society. Prostitution was censored, but tolerated; London was one of the cities with the most brothels in Europe. In society, husbands faithfully played their role as loving husbands and fathers; However, they maintained numerous lovers. Women could do it too, but, of course, they had to be much more discreet.

Victorian morality and sex

Talking about sex was unthinkable. Nothing was said to the young people about it. Evidently, the sexual act was absolutely restricted to marriage (or, at least, in theory). Consequently, Victorian society was eminently inhibited ; So much so that authors such as Rosa Aksenchuk, from the University of Buenos Aires, maintain that Freud’s psychoanalysis and advances in psychiatry were extraordinarily facilitated by society’s inhibition.

And of course, women were expected to be heavenly creatures who didn’t need sex. The roles of wife and mother already had to be sufficiently “satisfying” for them. Furthermore, let us remember that, In a world in which the majority of marriages were still of convenience, there was little room for sex for pleasure

As a result, and spurred by the difficulty they found in finding lovers, female sexual dissatisfaction grew. Her time baptized it with a curious name: “hysteria.” Doctors worked hard to alleviate the symptoms of this “disease” through “pubic massages,” which were nothing more than masturbation. Thus, through vaginal and clitoral stimulation, the dissatisfied wives found pleasure and an escape valve from their constraint.

As a curiosity, we can point out that this was the origin of female dildos. At first they were designed as “medical solutions” for hysteria, and were viewed as something strictly medicinal. Eventually, women got used to using them, and then society woke up: they were using it for their own pleasure! Puritan Victorian society had created the female dildo. Seeing is believing.