Throughout the 19th century, surgeries were a life or death gamble. Antisepsis was something unknown and even looked down upon, since many doctors considered that washing their hands or cleaning surgical instruments was unnecessary, even offensive to be asked to do such a thing.

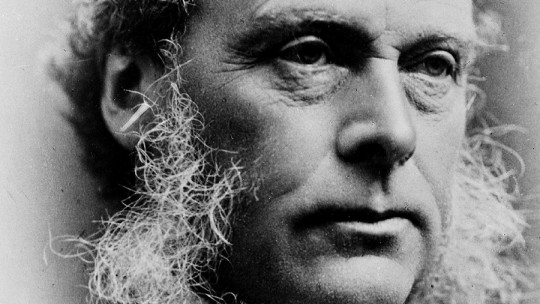

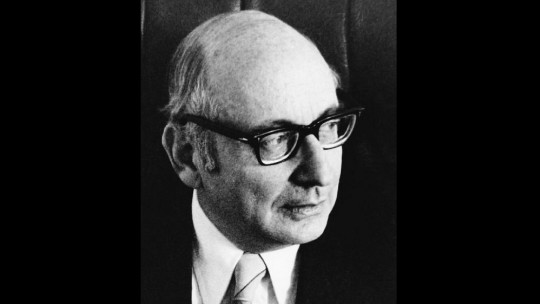

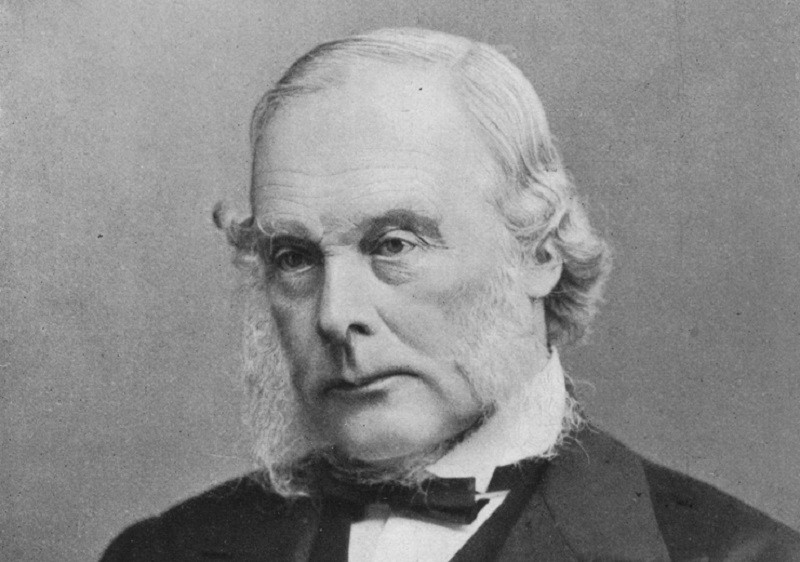

Fortunately, this has changed, although it would not have been possible without the influence of great figures such as Joseph Lister. This English doctor realized the great need to sterilize both the operating room and the instruments to be used in order to avoid the enormous number of deaths associated with nineteenth-century operations.

In this Joseph Lister biography We are going to discover the life of this British surgeon, his main discoveries and the significance of his work.

Brief biography of Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, First Baron Lister, was a British surgeon well known for his discoveries in antiseptic techniques and his awareness of the importance of maintaining proper hygiene and sterilization in operating rooms. This English doctor He realized that surgical wounds ended up rotting if they were not properly sanitized before and after the intervention guaranteeing the death of the patient due to sepsis.

Being aware of this, he introduced several antiseptic techniques in the operating rooms, in addition to imposing the now-normalized habit of hand washing, the original idea of the Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweiss. Although Lister abused a little carbolic acid, better known today as phenol, a quite toxic substance, it must be said that it was a good sterilant in its time and worked to prevent the death of thousands of people, causing a true revolution in the field of surgery.

Early years

Joseph Lister was born on April 5, 1827 into a prosperous Quaker family in Upton, Essex, England His parents were Joseph Jackson Lister and Isabella Harris. His father was a wine merchant who had extensive knowledge of physics and mathematics and, in addition, had a hobby of doing microscopy and optics work, being one of the first builders of achromatic lenses.

Lister studied at University College London, one of the few institutions that admitted Quakers at the time. He initially studied botany and graduated in 1847. After He enrolled in the study of Medicine, obtaining his degree with honors and, at the age of 26, was admitted to the Royal College of Surgeons of England In 1854 he trained as a surgeon officer in Edinburgh, along with Jarnes Syme, whose daughter he married. In the Scottish capital he dedicated himself to various anatomical, physiological and pathological works.

Beginnings in surgery

In 1860 he went to Glasgow where he replaced Syme and carried out his most extensive work. When he took charge of the surgical clinic in that city, Joseph Lister had to face what was one of the main problems of surgery at the time: Between 30 and 50% of the patients admitted ended up dying from hospital gangrene, erysipelas, pemia or purulent edema

Entering an operating room in the 19th century was a gamble of life or death. Although with the invention of anesthesia, operating rooms had become quieter places, without the agonizing screams of patients, postoperative illnesses ended up claiming almost half of those operated on.

The usual procedure to avoid infections was to ventilate the hospital rooms to expel the miasmas , the bad air that at that time it was believed that wounds exhaled and that they spread diseases to other patients. This was the only hygienic habit practiced by the surgeons of the time because, as surprising as it may seem to us today, they adored the putrid stench of the hospitals of the time.

The doctors arrived at the operating room in their street clothes and, without even washing their hands, put on their gowns covered in traces of dried blood and pus, seen as medals proof of the multiple operations they had performed.

The success of the operations was rather limited, a fact known to all surgeons as it was their daily bread. It was for this reason that even The surgeons themselves were reluctant to operate until it was absolutely essential and, in fact, the problem of infections was so serious that there was even talk of abolishing surgery in hospitals. It was preferable for the patient to die at his own expense rather than cause an agonizing and undignified death caused by the symptoms of septicemia.

But to Joseph Lister He was not convinced by the miasma theory, as he observed that by cleaning wounds he sometimes managed to contain infections The problem should not be in the air, but rather in the wound itself. Like other surgeons in the past, Lister wanted to rebel against the laudable pus doctrine, which held that pus was a positive sign of wound healing far from being indicative of infection and health risk. Lister confronted this doctrine, but he did so differently. He thought that infection of wounds and the formation of pus were comparable to putrefaction.

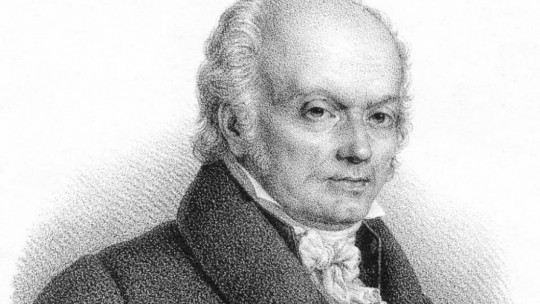

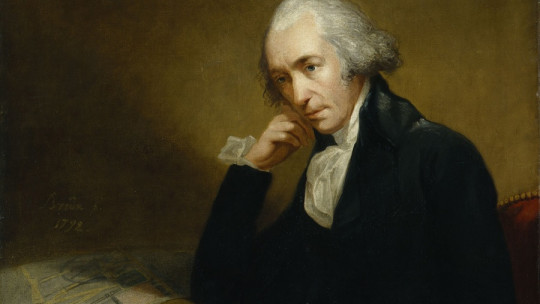

Lister knew about the ideas and works of Louis Pasteur. On the one hand, he knew that the French bacteriologist had demonstrated that putrefaction was due to the arrival of living germs to the putrescible matter, and on the other, that this same matter could be preserved unchanged if it was kept out of contact with the air or if the It itself arrived filtered. Lister related these notions to his experience in the field of surgery, especially with cases of fractures.

Discovery of the power of antisepsis

Joseph Lister had observed that simple fractures, those in which there was no injury, healed without too many problems , while open or complex ones normally ended with suppuration and infection. He thought that atmospheric air was responsible, because it introduced germs into the injured person’s body. His conclusion: it had to be filtered somehow.

Lister tried several alternatives: zinc chloride, sulfites… until he came across carbolic acid, currently better known as phenol, a substance that was easily obtained from coal tar and which, since 1859, had been used to prevent rot. Joseph Lister knew that carbolic acid had been used in the United Kingdom to prevent sewer stench and that In the fields where the waters with this substance flowed, the entozoans that parasitized the cattle disappeared

In 1867 he published a work entitled “On a new method of treating compound fracture, abscess, etc. with observations on the conditions of suppuration” (“New treatment of open fractures and abscesses; observations on the causes of suppuration”) that barely had any resonance among the scientific community. He later presented the results of a new study on the subject to the British Medical Association. He would end up publishing this material in book form in 1867 with the title “On the Antiseptic Principle in the Practice of the Surgery.”

Between the first publication and the second he improved his technique. He first applied compresses of carbohydrate water and then sprayed this substance both on the objects and in the air of the room where he was going to perform his interventions, completing the sterilization with the use of carbolic ointments on the wound. Every measure seemed insufficient to ensure that no germ infected the patient’s surgical wound

Successes in his career in Medicine

Little by little he accumulated a series of successful cases, the result of continued experience. In 1867 he decided to operate on a patient with a fractured tibia using his novel antiseptic method. Normally, most cases ended in tragedy. However, Lister managed to cure the patient with his method without any problem, being the beginning of what some call “listerism”, a current that began to quickly gain followers

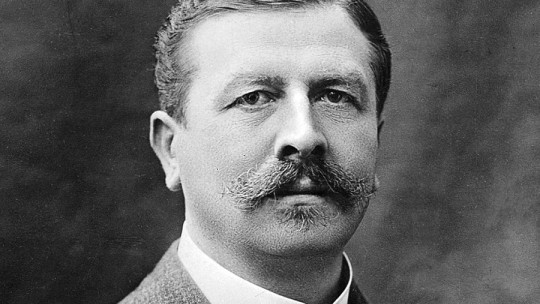

Relevant figures for surgery and medicine of the time were deeply interested in the antisepsis proposed by Joseph Lister: in Italy Antonio Bottini; in Germany Richard von Volkmann and Karl Thiersch; in France, Lucas Championnière; and in Spain Salvador Cardenal, Antonio Morales Pérez, Miguel Fargas, Nicolás Ferrer and Juan Aguilar y Lara.

However, there were also great figures of his time who did not take him seriously or were convinced by his ideas. Among them was R. Lawson Tait, of Birmingham, who even said that antisepsis was a useless complication for surgeries, although the evidence would eventually change his mind.

Knowing the value of statistics to give strength to his arguments, Lister accumulated data and figures By 1870 he presented his results regarding amputations. Before the use of their antiseptic techniques, mortality was close to 50% of the patients who underwent surgery, while after their use this decreased to 15%. Death

Joseph Lister died on February 10, 1912 at the age of 84, having received all kinds of honors, tributes and recognition for his work. Although at first he aroused all kinds of criticism and skepticism, His antisepsis would end up being one of the three great discoveries that would cause the revolution in surgery, along with anesthesia and hemostasis His funeral was held at Westminster Abbey, where his effigy was engraved alongside those of John Hunter and Francis Willis.

Honors and recognitions

Although from our modern vision hygiene and sterilization are essential aspects prior to surgery, this was not the case in the 19th century. Therefore, Joseph Lister had the idea that to guarantee the success of the operations and a safe postoperative period, good cleaning of hands and surgical instruments was necessary, in addition to making sure that the room was as clean as possible, it was an idea visionary.

Despite the initial skepticism of his proposals, it was a matter of little time before the results supported his method saving thousands of lives and making Lister worthy of several honors, which we mention below:

- 1883: created Baronet of Park Crescent, Marylebone (Middlesex)

- 1897: created Baron of Lyme Regis

- 1902: receives the Order of Merit.

- 1895-1900: President of the Royal Society

- 1910: the National Autonomous University of Mexico grants him the Honoris Causa

- The genus Listeria is named in his honor.

- The product “Listerine” is named in his honor.

His last name has been registered naming a genus of microorganisms from the Corynebacteriaceae family , order Eubacteriales: Listeria. The microorganisms belonging to this genus are gram-positive coccoid and bacillary, which are usually found in animals and cause sepsis. It can also infect humans causing an upper respiratory disease with lymphadenitis and conjunctivitis, and also sepsis that can cause encephalitis.

As a final curiosity, the product Listerine, a well-known oral antiseptic, is named in his honor. Joseph Lister was not its inventor nor did he benefit from it, but it is worth mentioning that it could not have been invented if the importance of sterilizing human wounds and tissues to prevent infection had not been discovered.