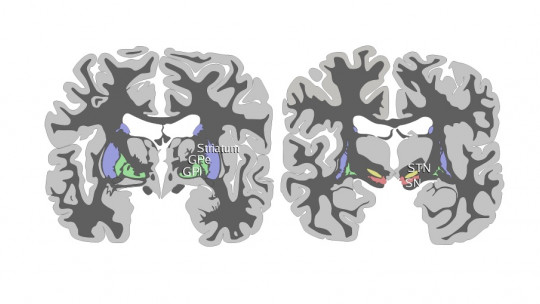

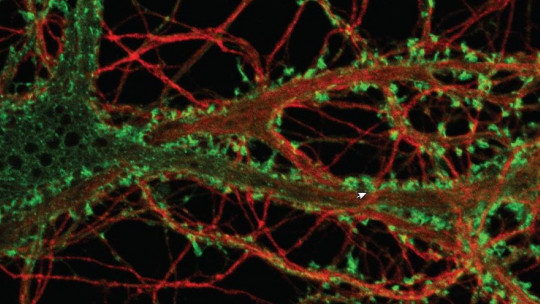

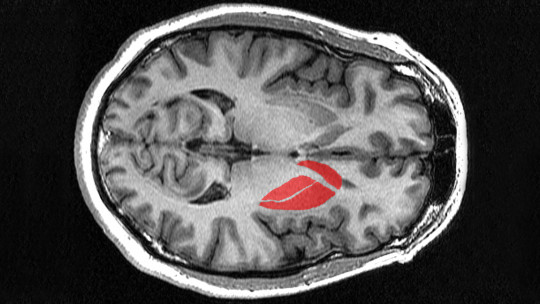

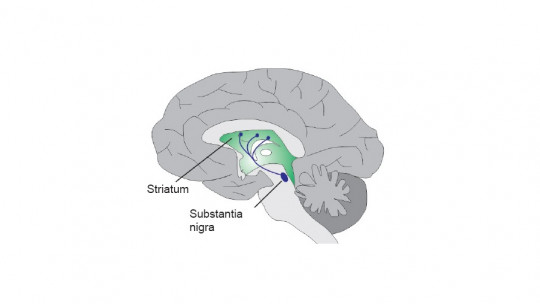

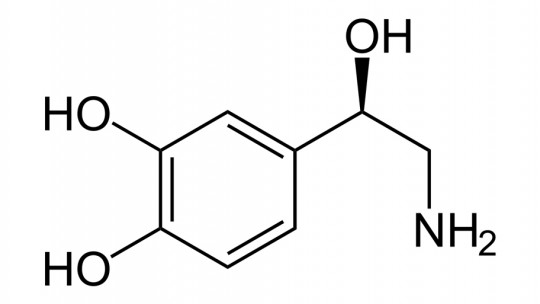

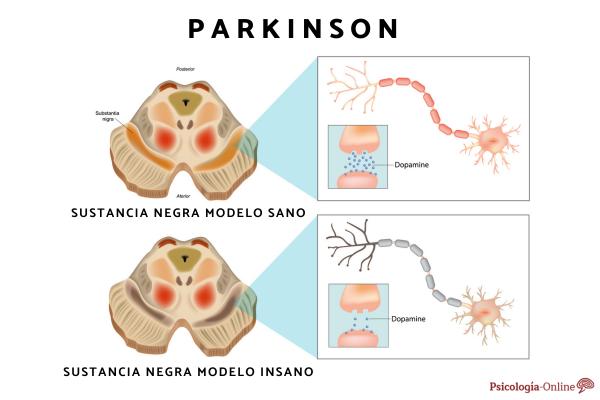

Parkinson’s disease (PD hereinafter) is an incurable neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system, only relieved by drugs or neurosurgery, not preventable, progressive, with a tendency to invalidation. It’s not deadly. It is produced by the degeneration of neurons that secrete a specific neurotransmitter, Dopamine, in the mesencephalic area known as the basal ganglia; Specifically, up to 70% of the dopaminergic neurons in the “substantia nigra” and striatum are lost. Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter necessary for the regulation of movements, walking and balance. In this PsychologyOnline article, we will talk about Neurosciences of Parkinson’s Disease

About Parkinson’s disease.

PD is the second neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s disease. Some 110,000 people are affected in Spain. It affects men and women equally, and especially older people (1.7% of those over 60 years of age), although 20% of patients are under 50 years of age. Its causes are multiple and not yet fully known: genetic, metabolic, apoptosis, cellular oxidation, environmental toxins, old brain microtrauma, etc.

It is not a recent disease: it was already masterfully described in 1817 by Sir James Parkinson, who named it “Agitating Paralysis” thus highlighting its two components: akinesia (paralysis) and the earthquake (agitation). In fact, the four clinical criteria for its diagnosis are:

- Tremors of 4-8 Hz, predominantly resting.

- Bradykinesia, that is, generalized slowness of movement

- Stiffness, that is, muscle hypertonia

- Balance disorders (falls, freezing of movements)

Although motor symptoms are the most noticeable and main in PD, more and more attention is being paid to the existence of a parallel series of cognitive disorders and even dementia.

Mild and medium cognitive impairment.

A series of deficits of different basic mental functions (memory, attention, perception, mental agility, strategy planning, etc.), of different presentation due to intensity and globality in each patient, but almost always present. Such deficient cognitive symptoms can be detected, in a very mild way, from the beginning of the diagnosis of the condition in patients not yet medically treated.

Although without showing a completely direct relationship, cognitive problems usually go in parallel with the progression and severity of the disease. When they appear very early, it is a poor prognostic index for the course of the disease, or that it is not really a genuine PD but a related disease (diffuse Lewy body disease, cortico-basal atrophy, etc.). We now detail such typical cognitive deficits of PD, as they appear in the summary in TABLE 1.

BRADYPSYCHIA

Patients with PD almost all show moderate to severe slowing of the speed of thinking and information processing, with increased neurological reaction time (evoked potentials of P300 waves). For this reason, they take time to understand a question and generate an answer to a question, although the basic logic applied is not very altered.

MEMORY

Subjective complaints of “bad memory” are frequently reported by PD patients, but the full amnestic syndrome typical of Alzheimer’s does not appear. Long term memory It is more damaged than short-term memory, the opposite, for example, of Alzheimer’s Disease. The recognition of what has been learned (evocation with guides or aids) far exceeds what is remembered freely and spontaneously, which also occurs in Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) but not in Alzheimer’s (a disease that no longer benefits from “clues” to guided remembering). episodic memory (location of events in a spatio-temporal context) is somewhat impaired, also less than in Alzheimer’s. Semantic memory (general data recall), and the implicit (procedural, priming) are noticeably more preserved than in Alzheimer’s. See TABLE 2. In general, PD shows slowness in remembering and difficulties in accessing stored data, which “are there”, but the patient does not know how to get to them.

DIS-EXECUTIVE SYNDROME

The cognitive deficits of Problem resolution: planning and defining objectives, sequencing steps to achieve them, putting the plan into action, self-monitoring of the process (self-evaluation), making decisions to modify the plans… The PE also shows poor mental flexibility and great cognitive rigidity, it is difficult for him to change strategies quickly, he tends to persevere ideas (obsessive type pattern), it is not easy for him to handle two problems at the same time, little creativity… These symptoms are related to dysfunctions of the frontal lobes, and occur with less intensity and later than in Huntington’s disease or PSP.

ATTENTION

Shows the EP deficit in maintaining active attention and concentration for a long time. He gets tired quickly, and the emotional lack of motivation that the patient frequently shows contributes. This also contributes to memory problems, because what was not paid attention to is not well remembered (due to poor encoding processes), and to a decrease in learning capacity.

PERCEPTIVE DISORDERS

Visuo-spatial perception is the one that is most altered centrally, apart from peripheral oculomotor problems. Patients with PD they do not perceive distances well, the relative position between various objects, vision in three dimensions, the clarity of the images, it even seems that there is greater perseveration of visual perceptions than should be (the visual sensory memory is not “erased” quickly, and some sensations may interfere previous visuals with new ones). Furthermore, the PD patient shows, like PSP, difficulties attending to “multisensory” channels at the same time (e.g., seeing and hearing simultaneously), these channels powerfully interfering, canceling each other out or creating confusion.

Dementia.

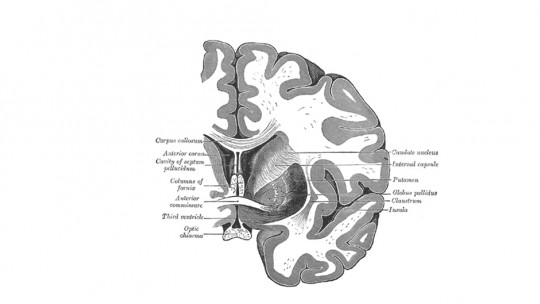

Didactically, two types of dementia can be differentiated: the cortical (Alzheimer type) and the subcortical or frontosubcortical (Huntington type), whose characteristics I summarize in TABLE 3. However, clinical practice shows numerous patients with mixed symptoms and transitional symptoms. Summarizing, we would say that Alzheimer’s Disease is the classic representative of cortical dementia, Diffuse Lewy Body Disease would show a mixed dementia of both cortico and subcortical, PSP would be included in the predominantly frontosubcortical and secondarily cortical dementias, and the Disease Parkinson’s would be more representative of subcortical dementias. It is generally accepted that Cortical dementias are more deteriorating than subcortical dementias We move on to detail the case of dementia in PD.

FRONTOSUBCORTICAL DEMENTIA

With the evolution of the disease over many years, almost one in three PD patients will show dysexecutive, bradyphrenic, and attention-memory problems so intense that they interfere with their personal and social life in a clinically significant way, leading to the diagnosis of “subcortical dementia” with a certain conceptual consistency. The problem is that the operational criteria for such a diagnosis are not clearly described in any international manual such as DSM-IV of the APA or ICD-10 of the WHO, nor is there a standard neuropsychological battery with precise cut-off points. This type of dementia occurs with a lower incidence in genuine (idiopathic) Parkinsonism than in Parkinsonisms such as multiple system atrophies (Shy-Drager type syndromes) or PSP.

CORTICAL DEMENTIA

Classic cortical symptoms such as profound amnesia, apraxia, aphasia, agnosia and complete disorientation are rare in PD, which is why this diagnosis of “Alzheimer’s dementia” does not occur in more than 10% of PD patients. although partial or incomplete cortical symptoms do appear. Just note that, given the advanced age of PD, this disease can occur simultaneously with Alzheimer’s in the same patient, and both diagnoses must then be received.

Other neuropsychological signs.

In PD, a series of symptoms are repeatedly described. emotional or character symptoms that can be related to the neurodegenerative disease itself (alteration of the balance between neurotransmitters: dopamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine, serotonin, GABA; hypofunction of diencephalic and cortical structures) and not only as an experiential psychological reaction to suffering from a chronic disease, or as side effects of psychoactive medication.

Typical are the references to depression (neurogenic-endogenous), apathy and abulia, flattening of the personality, emotional hyporeflexia, hyposexuality, obsession-compulsion, sleep disorders. Psychotic (hallucinations, delusions) and confusional symptoms do not belong to the natural history of PD, but are actually unwanted side effects (iatrogenesis) induced by dopaminergic medication taken at high doses or for many years.

Neuropsychological cognitive evaluation.

Without wishing to be exhaustive, we will mention as useful in PD: As extensive multidimensional batteries, the Peña-Casanova Barcelona (PIEN-B) and abbreviated version (TB-A), the Wechsler WAIS-R scales, the Neuropsychological Examination of Luria, and the Cambridge Cognitive Examination (CAMCOG, which is part of the broader CAMDEX). Quick tests for assessing cortical deficit or dementia can be the Mini Mental (MMSE by Flostein and Spanish version MEC by Lobo) and the Shulman Clock Test (CDT). Also scales such as the Blessed Dementia Rating (DRS), Hughes Clinical Dementia Assessment (CDR), Reisberg Global Impairment Scale (GDS, FAS), and Informant Test (TIN, Spanish version of the Jorm-Korten IQCODE ).

Specific tests are:

- The Frontal Functions Assessment Battery (FAB, studied in Spain by us) for the detection of frontal dysexecutive syndrome;

- The Wisconsin Cards (WCST) for abstract reasoning and cognitive flexibility; the color-word Stroop for response interference;

- He TAVEC as evidence of verbal memories; the Rivermead (RBMT) as a procedural-behavioral memory test; the Memory Failures Questionnaire (MFE) for subjective complaints;

- He Bender-King-Benton (TGVM-TFC-TRVB) in visuo-spatial, execution and visual memory skills; the Tracing Test (TMT AyB, Halstead-Reitan) as a visual-motor and conceptual test;

- Raven’s Matrices as a test of the current level of abstract reasoning and the Word Stress Test (TAP) as an estimate of initial pre-morbid intelligence;

- The Tower of Hanoi and Kohs Cubes in planning and problem solving. The evaluation is usually complemented with the Cummnings Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) and the Yesevage Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).

Supplementary tables

TABLE 1

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS IN PARKINSON’S DISEASE

1- Partial Cognitive Deficits

- Bradypsychia (slowness of thought)

- Memory disorders

- Dys-Executive Syndrome

- Perception alteration (visuo-spatial)

- Low attention

- Little cognitive flexibility

- Mental fatigue

2- Dementia

- Frontosubcortical

- Cortical

- Mixed

3- Other disorders

- Flattening of personality

- Apathy and apathy

- Anergy and areflexia

- Neurogenic depression

- Obsession-compulsion

TABLE 2

MEMORY ASSESSMENT

1- Subjective patient complaints

2- Sensory memories (immediate)

3- Short-term memory

- attentional component

- visuospatial component

- articulatory component

4- Long-term memory

- Declarative or explicit

- Semantics

- Episodic

- Procedural or implicit

- Priming

- Other behavioral

TABLE 3

TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF DEMENTIA

Dementia: Cortical – Subcortical

Disease Alzheimer-Parkinson

Deterioration More homogeneous – Not Provided

Night gets worse But

Memory Forgetfulness, Amnesia – Difficult access

Orientation Disorientation -Oriented

Knowledge Agnosia – Bradypsychia

Execution Apraxia – Dysexecution

Language Aphasia – Normal

Speaks Normal initial – Dysarthria

Calculation Errors – Slowed down

Cognitions Deteriorated – Poor use

Psychotic symptoms Due to illness – Due to medication

Keen Normal-Anxious – Depressive

Personality Normal-Inappropriate – Apathetic

Position Normal – Incline

March Normal – Altered

Movements Normal – Slow

CoordinationInitial normal – Early affected

cortex Affected – Variable affectation

basal ganglia Little affected – Affected

Neurotransmitter Acetylcholine – Dopamine, others

Deadly medium term But

quick test MMSE – FAB

TABLE 4

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION

1- General level of awareness

2- Temporal, spatial, and personal orientation

3- Attention and Concentration

4- Immediate, short-term, and long-term memory

5- Expressive and receptive language

6- Reasoning and Judgment

7- Gnosias (recognitions)

8- Praxias (skills)

9- Frontal executive capabilities

10- Learning

11- Sensory-perception

12- Pseudo-psychiatric symptoms

13- Behavioral observations (impulsivity, perseveration…

This article is merely informative, at PsychologyFor we do not have the power to make a diagnosis or recommend a treatment. We invite you to go to a psychologist to treat your particular case.

If you want to read more articles similar to Neurosciences of Parkinson’s Disease we recommend that you enter our Neurosciences category.