Androcentrism is the tendency to position the male experience in the center of explanations about the world and about individuals in a generalized way. It is a practice that often goes unnoticed and through which the perspective of men is assumed as the universal perspective, and even the only valid or possible one.

This has been a very present trend in the development of Western societies, and it has also been questioned significantly by different people, so it is worth reviewing what androcentrism is and where it has been most present.

The philosophy of who we put at the center

Something that contemporary philosophies and sciences have taught us is that there are many ways of looking at and explaining the world. When we perceive and interpret what surrounds us, and even ourselves, We do it based on a certain framework of knowledge

We have built this framework of knowledge throughout our history and largely through the stories we have heard about ourselves and others. That is to say, the knowledge we have acquired has to do with the different perspectives that have been placed, or not, at the center of the same knowledge.

Thus, for example, when we talk about anthropocentrism, we are referring to the philosophical tendency and conception that places the human being at the center of knowledge about the world, an issue that formally began with the modern era, and that replaced theocentrism (the explanations that put God at the center). Or, if we talk about “Eurocentrism” we are referring to the tendency to look at and construct the world as if we were all Europeans (the experience is generalized).

These “centrisms” (the tendency to place a single experience at the center and use it to explain and understand all other experiences), include both everyday and specialized knowledge. While they are at the base of our knowledge and practices in both fields, they easily go unnoticed.

What is androcentrism?

Returning to the previous section, we can see that “androcentrism” is a concept that refers to the tendency to explain the phenomena of the world based on the generalized experience of a single subject: man. This phenomenon consists of incorporate into scientific, historical, academic and everyday stories, the male experience at the center (that’s why it is “andro”, which means masculine gender; and “centrism”: in the center).

Consequently, all other ways of knowing and living the world are incorporated in these stories only peripherally, or are not even incorporated. This applies to many fields. We can analyze, for example, androcentrism in science, androcentrism in history, in medicine, in education, in sports, and many others.

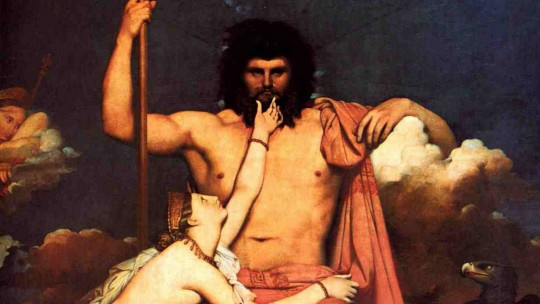

This is a phenomenon that has emerged largely as a result of the fact that in our societies, Men are the ones who have occupied the majority of public spaces and it is fundamentally in the public sphere where those practices and discourses have been developed that later allow us to know the world in one way or another.

These practices are, for example, science, history, sports, religion, etc. In other words, the world has been constructed and perceived fundamentally by men, so it is their experiences that have become historically extensive: much of how we see the world and how we relate to it is made from their perspective. , interests, knowledge, and general readings of everything that makes him up (that is, from his worldview).

Where can we see it?

The above is finally related and is visible in the most everyday, in the rules that tell us how to relate, how to behave, how to feel and even in the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves.

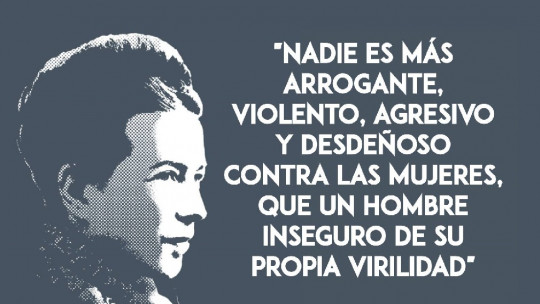

The latter means that, far from being a phenomenon that is located and caused specifically by the male gender, it is a process that we have all incorporated as a part of the same history and the same society And its main consequence has been that the experience of women and those who do not identify with the hegemonic model of “male” remains hidden and invisible, and therefore difficult to incorporate on equal terms.

For the same reason, there have been several people (mainly women) who have asked themselves, for example, Where have the women who did science been? Why do they practically only teach us the biographies of men? And the women who made history? Where are the stories of women who have lived through wars or revolutions? In fact, who has finally gone down in history? Under what models or imaginaries?

The latter has allowed it to recover more and more, and in different areas, the heterogeneity of the experiences we share in the world and with this, different ways of relating, perceiving and interpreting both what surrounds us and ourselves are also generated.