Can advertising be art? To answer this question, we should first ask ourselves what exactly we call art. Because only by delimiting this concept can we study whether, in fact, advertising can also be.

This is, as we see, a much more complex issue than it may seem at first glance. If, when we think about advertising, the first thing that comes to mind is the typical television advertisement, our answer is probably a resounding no. However, the paths of art and advertising constantly merge; and not only now, but in all times of history. Next, we question the relationship between art and advertising.

Can advertising be art? A complex question

OK. We have said in the introduction that, to unravel the answer to such a thorny question, we must first define what art is. However, it is a concept that always escapes a precise definition. Is it something we excite others about? Is it (only) beauty? Is it about the way in which human beings transmit beauty? Can art be related to darker and, shall we say, not so beautiful aspects of human reality?

Although it is difficult for us to admit it, the answer will depend on the time in which we find ourselves and, of course, the culture in which we are immersed. Our concept of art as beauty is the child of the academies of the 18th and 19th centuries, which considered art as a transmission of a series of artistic precepts that, in addition, were surprisingly fixed and corseted. In this sense, the (magnificent, on the other hand) works of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), the famous neoclassical painter, are probably some of the little that can be considered “art”.

What, then, about the other art, that which escapes the definition of the academies? What happens to medieval art, far from academicism of course, and what happens to the art of primitive peoples? Again, if we do not know (or cannot) define the definition of what art is, it will be frankly difficult for us to decide whether, in fact, advertising can be art as well.

Art has a lot to tell us

Let us return again to the academic art of the 18th and 19th centuries. It is evident that, like any image, these works had a message to transmit to the viewer, but this was always subordinated to the form. In the famous painting The Abduction of the Sabine Women, by the aforementioned David, the legend that the artist captures on the canvas (known by everyone, in fact) is not as important as the composition itself and the splendid anatomical study of the naked bodies. The form is above its message.

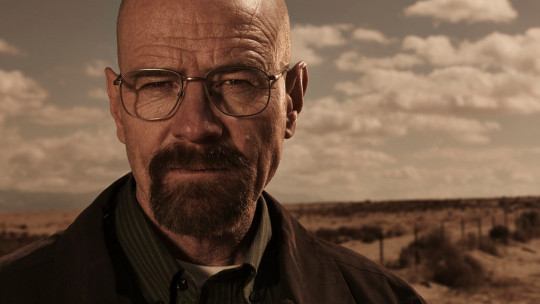

But, without moving from that same century, we find representations of Napoleon that, beyond offering impeccable academic beauty, are a pure image of power. The emperor transmutes himself into a kind of Olympian god to convey to the people that his will is only second to that of God. This same idea of power is what we find in the Augustus of Prima Porta, a splendid Roman work that shows us the emperor Octavian dressed in his attributes of power, to make clear, in this way, his unquestionable and divine right.

What do we mean by that? That, throughout history, Art has not only served to transmit beauty, but it has always been a precious ally of the powerful, through which the power in power has spread a legitimizing image of its position. Simply put: art is also persuasive.

When art and advertising shook hands

And what is more persuasive than advertising? The various effigies of Napoleon, the Augustus of Prima Porta, as well as the Portrait of Charles V on horseback by Titian (among many, many more examples) have an obvious propaganda load, although this goes much more unnoticed than the typical propaganda art of the 20th century. Art has always been used to manipulate, whether we like it or not.

So, we have that art can be persuasive, so, obviously, it can be used for propaganda and advertising purposes. You only have to look at the history of advertising to realize this. In the golden age of advertising posters, that is, the late 19th and early 20th centuries, designers were the most famous artists of the time. The Catalan Ramon Casas, the French Toulouse-Lautrec and the Czech Alphonse Mucha are three of the best-known names in this field, who elevated the advertising poster to the category of authentic art.

In fact, it is known that passers-by tore the posters from the street to collect them in their homes, as if they were paintings or prints. Of course, no one collects an advertising poster if it does not awaken a certain aesthetic desire in them, that is, if they do not feel pleased with what they see. Thus, we can say that it was in the final years of the 19th century when advertising and art finally joined hands and created a unique language that has been called posterism. And who could say that the wonderful posters of Lautrec, Casas, Mucha and so many others are not art…?

Between advertising and propaganda

In the same way as with the definition of art and advertising, we find that the line that separates advertising and propaganda is equally complex. Both aim to persuade and convince, this is indisputable. However, while advertising focuses more on the sale of a product, propaganda is much more related to the sale of ideas, especially political ones.

During the Great War (1914-1918) propaganda posters proliferated, encouraging enlistment and feeding the idea that the “others” were the true monsters who had to be annihilated. In this sense, art was put at the service of a macabre idea that encouraged hatred, war and manipulation. But then again, can we call that art?

From an aesthetic point of view, yes. Many of these posters were designed by true artists, and in many we find a drawing of extraordinary quality that links directly to the avant-garde currents of the time. Therefore, in this sense, yes, the propaganda poster is art, because art does not have to be beautiful. Otherwise, we could not call Goya’s lurid (but magnificent) black paintings art either.

This idea links with another, that of art as a vehicle of denunciation. Direct heirs of the black paintings of Goya (a true visionary who was a hundred years ahead of his time) we find the German expressionists, who achieved, with an aesthetically repulsive painting (that is, that appealed to the darkest part of the human being and did not followed, of course, no academic standard) to shake up interwar society and put before its nose the drift into which the world was precipitating. Art can also denounce, of course.

Conclusions

Can advertising be art? Our conclusion is yes. Not only because behind marketing campaigns are often authentic artists with great inspiring ideas (many of them taken from great artistic works), but also because art has always been, since time immemorial, a vehicle to persuade.

It would be a mistake to understand art (alone) as a mere expression of beauty. Because, from this perspective, we would have to discard painters like Goya, Schiele, Kirchner, or even Hieronymus Bosch and Brueghel. Art not only transmits beauty, but also proposes ugliness, darkness, disgust and rejection. Art has the ability to move, but also to shake consciences and, of course, it also has the gift of convincing. The leaders of the past, such as Augustus, Charles V or Napoleon, knew this perfectly, and today’s publicists also know it. Art appeals to emotions, and emotions, as we already know, are a direct route to action.