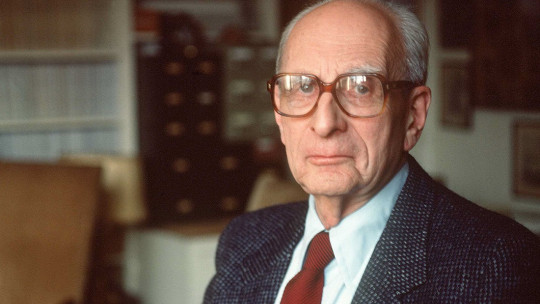

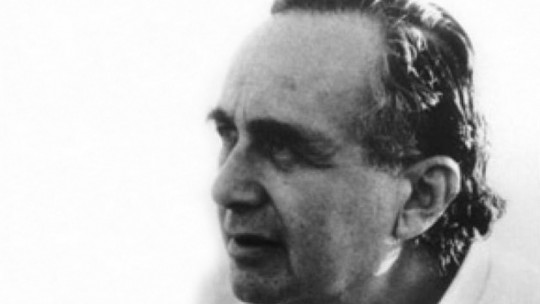

Claude Lévi-Strauss was a French anthropologist and one of the most prominent social scientists of the 20th century.

He is best known for being the founder of structural anthropology and for his theory of structuralism. Furthermore, he was a key figure in the development of modern social and cultural anthropology, and had great influence outside his discipline.

In this article we present the figure of Claude Lévi-Strauss, his life and career, as well as his main theoretical and philosophical contributions.

Claude Lévi-Strauss: life and career

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908 – 2009) was born into a French Jewish family in Brussels and later raised in Paris. He studied philosophy at the historic Sorbonne university Several years after his graduation, the French Ministry of Culture invited him to teach as a visiting professor of sociology at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, a position he held as a teacher, after moving to this country, until 1939.

In 1939, Lévi-Strauss resigned to conduct anthropological fieldwork in indigenous communities in the regions of Mato Grosso and the Brazilian Amazon, beginning the beginning of his research on indigenous groups in the Americas. The experience would have a profound effect on his future, paving the way for a groundbreaking career as a researcher and intellectual. He achieved literary fame for his 1955 book “Tristes Trópicos,” in which he recounted part of his time in Brazil.

Lévi-Strauss’s academic career began to take off when World War II hit and he was lucky enough to escape France for the United States, thanks to a teaching position at the New Research School in 1941. While in New York He joined a community of French intellectuals who successfully found refuge in the United States, amid the fall of their home country and the rising wave of anti-Semitism in Europe.

Lévi-Strauss remained in the United States until 1948, joining a community of Jewish scholars and artists who escaped persecution that included the linguist Roman Jakobson and the surrealist painter André Breton. Additionally, he helped found the Escuela Libre de Altos Estudios (French School of Free Studies) with other refugees, and later worked as a cultural attaché for the French embassy in Washington DC.

Lévi-Strauss returned to France in 1948, where he received his doctorate from the Sorbonne. He quickly established himself within the ranks of French intellectuals and was director of studies at the School of Free Studies at the University of Paris from 1950 to 1974. He became chair of Social Anthropology at the famous Collège de France in 1959 and held the position until 1982.

structuralism

Claude Lévi-Strauss formulated his famous concept of structural anthropology during his stay in the United States In fact, this theory is unusual in anthropology in that it is inextricably linked to a scholar’s writing and thinking. Structuralism offered a new and distinctive way of approaching the study of culture, and built on the academic and methodological approaches of cultural anthropology and structural linguistics.

Lévi-Strauss argued that the human brain is wired to organize the world in terms of key organizing structures, allowing people to order and interpret experience. Because these structures are universal, all cultural systems are inherently logical. Different systems of understanding are simply used to explain the world around them, resulting in the surprising diversity of myths, beliefs and practices. According to Lévi-Strauss, the task of the anthropologist is to explore and explain the logic within a particular cultural system.

Structuralism used the analysis of cultural practices and beliefs, as well as the fundamental structures of language and linguistic classification, to identify the universal building blocks of human thought and culture. This philosophical current offered a fundamentally unifying and egalitarian interpretation of people from around the world and from all cultural backgrounds. Lévi-Strauss maintained that all people use the same basic categories and organizational systems to make sense of human experience.

Lévi-Strauss’s concept of structural anthropology aimed to unify, at the level of thought and interpretation, the experiences of cultural groups living in highly variable contexts and systems, from the indigenous community he studied in Brazil to the French intellectuals of the Second World War. The egalitarian principles of structuralism were an important intervention because they recognized all people as fundamentally equal, regardless of culture, ethnicity, or other socially constructed categories.

The myth theory

Lévi-Strauss developed a deep interest in the beliefs and oral traditions of Native Americans during his time in the United States. Anthropologist Franz Boas and his students pioneered ethnographic studies of North American indigenous groups, compiling vast collections of myths. Lévi-Strauss, in turn, sought to synthesize them in a study that covers the myths from the Arctic to the tip of South America

These investigations culminated in his work “Mythologies,” a four-volume study in which Lévi-Strauss argued that myths could be studied to reveal the universal oppositions (such as death versus life or nature versus culture) that organized the human interpretations and beliefs about the world.

Lévi-Strauss presented structuralism as an innovative approach to the study of myths. One of his key concepts in this regard was “bricolage,” a concept he borrowed from French to refer to a creation that is based on a diverse variety of parts. The “bricoleur”, or the individual involved in this creative act, makes use of what is available. For structuralism, both concepts are used to show the parallelism between Western scientific thought and indigenous approaches; They are both fundamentally strategic and logical, and simply make use of different parts.

The theory of kinship

Claude Lévi-Strauss’s earlier work focused on kinship and social organization, as described in his 1949 book, “The Elementary Structures of Kinship.” In this sense, Lévi-Strauss tried to understand how the categories of social organization, such as kinship and class, were formed. He understood these concepts as social and cultural phenomena, not as natural (or preconceived) categories; However, the question he asked himself was: what caused them?

Lévi-Strauss’s writings focused on the role of exchange and reciprocity in human relationships He also became interested in the power of the incest taboo to push people to marry outside their family, and the subsequent alliances that emerge from these situations.

Rather than approaching the incest taboo as a product with a certain biological basis or assuming that lineages must be traced through family descent, Lévi-Strauss focused on the power of marriage to create powerful and lasting alliances between families.

Criticisms of Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism

Like any other social theory, Structuralism was not without criticism Later researchers broke with the rigidity of Lévi-Strauss’s universal structures to adopt a more interpretive (or hermeneutic) approach to cultural analysis.

Likewise, the focus on underlying structures potentially obscured the nuances and complexity of lived experience and everyday life. Marxist thinkers also criticized the lack of attention to material conditions, such as economic resources, property, and class.

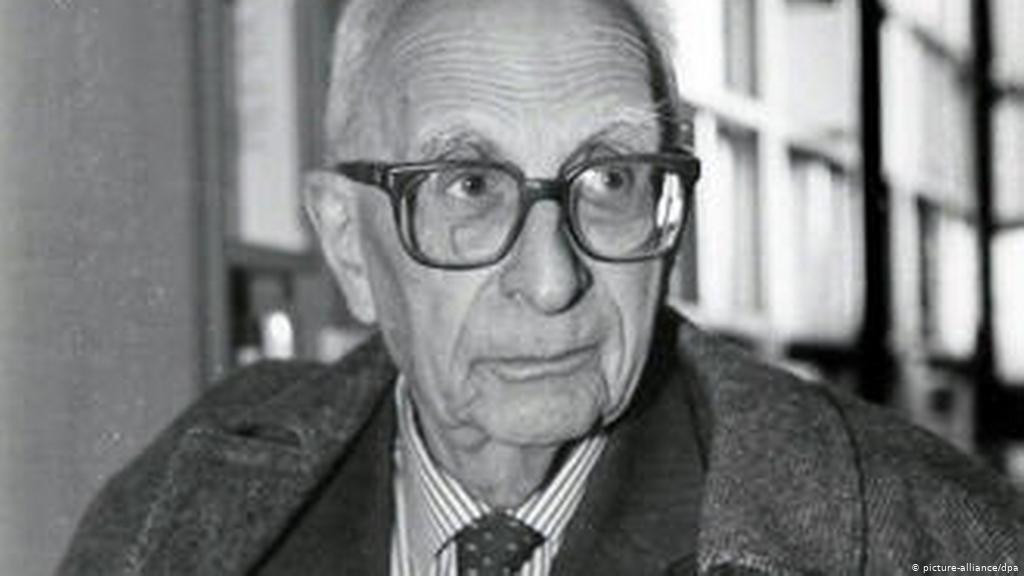

Another criticism of Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism came from Clifford Geertz, one of the greatest exponents of symbolic anthropology. Geertz criticized that his doctrine did not take into account historical factors and that it underestimated the emotional dimension of the human being and questioned the very possibility of subjecting polymorphic patterns of behavior and human beliefs to a closed systematic analysis in accordance with rules.

In short, Geertz’s proposal consisted of deepening local knowledge, which according to him helps us relate to others. According to him, the important thing was not to study whether or not culture has a grammatical meaning or a structure where man can act, but rather to know its semiotic meaning.

For Geertz, the human being is an animal inserted in webs of meaning and that is why the question of knowing whether culture is structured behavior or a structure of the mind, or even the two things mixed together, does not make sense.