Before Psychology appeared as a science, it was the task of philosophers to investigate the way in which human beings perceive reality. Starting with the Renaissance, two great philosophical currents fought against each other to answer that question; On the one hand there were the rationalists, who believed in the existence of certain universal truths with which we are already born and that allow us to interpret our surroundings, and on the other there were the empiricists, who They denied the existence of innate knowledge and they believed that we only learn through experience.

David Hume was not only one of the great representatives of the empiricist movement, but he was also one of the most radical in that sense. His powerful ideas still have relevance today and, in fact, other philosophers of the 20th century were inspired by them. Let’s see What exactly was David Hume’s empiricist theory?

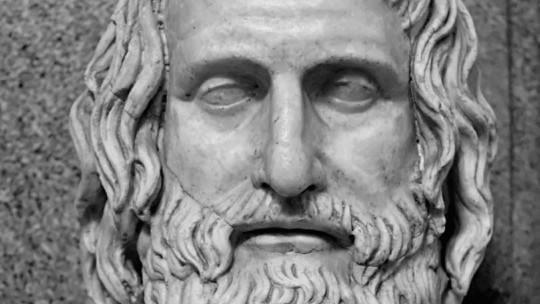

Who was David Hume?

This English philosopher was born in 1711 in Edinburgh, Scotland. At only twelve years old he entered the University of Edinburgh to study, and years later, after suffering a nervous breakdown, he moved to France, where he began to develop his philosophical concerns through the writing of Treatise on Human Nature, completed in 1739. This work contains the germ of his empiricist theory.

Much later, around 1763, Hume he became friends with Jean-Jacques Rousseau and he began to become more known as a thinker and philosopher. He died in Edinburgh in the year 1776.

Hume’s empiricist theory

The main ideas of David Hume’s philosophy They are summarized in the following basic principles.

1. There is no such thing as innate knowledge

Human beings come to life without prior knowledge or thought patterns that define how we should conceive reality. Everything we will come to know will be thanks to exposure to experiences

In this way, David Hume denied the rationalist dogma that there are truths that exist by themselves and to which we could have access in any possible context, only through reason.

2. There are two types of mental content

Hume distinguishes between impressions, which are those thoughts that are based on things that we have experienced through the senses, and ideas, which are copies of the previous ones and their nature is more ambiguous and abstract as they do not have limits or details. of something that corresponds to a sensation caused by eyes, ears, etc.

The bad thing about ideas is that, despite corresponding exactly to the truth, they tell us very little or nothing about what reality is like, and in practice what matters is knowing the environment in which we live: nature.

3. There are two types of statements

When explaining reality, Hume distinguishes between demonstrative and probable statements. Demonstratives, as their name indicates, are those whose validity can be demonstrated by evaluating their logical structure. For example, saying that the sum of two units equals the number two is a demonstrative statement. This implies that its truth or falsity is self-evident without the need to investigate other things that are not contained in the statement or that are not part of the semantic framework in which that statement is framed.

The probable ones, on the other hand, refer to what happens in a certain time and space, and consequently it cannot be known with complete certainty if they are true at the moment in which they are stated. For example: “tomorrow it will rain.”

4. We need probable statements

Although we cannot completely trust its validity, we need to support ourselves with probable statements to live, that is, trust more in some beliefs and less in others. If not, we would be doubting everything and doing nothing.

So, what are our habits and way of living following solid beliefs based on? For Hume, the principles by which we are guided are valuable because they are likely to reflect something true, not because they correspond exactly to reality.

5. The limitations of inductive thinking

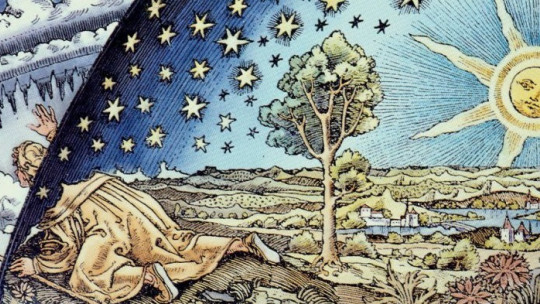

For Hume, our lives are characterized by being based on the belief that we know certain invariable characteristics about nature and everything that doesn’t surround it. These beliefs are born from exposure to several similar experiences.

For example, we have learned that when you turn on the tap two things can happen: either liquid falls or it does not fall. However, it cannot happen that liquid comes out but, instead of falling, the jet is projected upwards, towards the sky. The latter seems obvious, but, taking into account the previous premises… what justifies that it will always continue to happen in the same way? For Hume, there is nothing that justifies it. From the occurrence of many similar experiences in the past, It does not follow logically that this will always happen

So, although there are many things about how the world works that seem self-evident, for Hume these “truths” are not really so, and we only act as if they are out of convenience or, more specifically, because they are part of our routine. First we expose ourselves to a repetition of experiences and then we assume a truth that is not really there.