Edward C. Tolman was the initiator of propositional behaviorism and a key figure for the introduction of cognitive variables in behavioral models.

Although The study of cognitive maps is Tolman’s best-known contribution this author’s theory is much broader and represented a true turning point in scientific psychology.

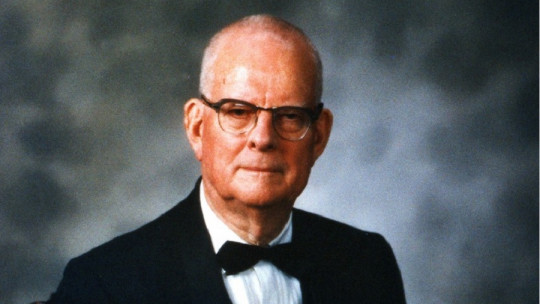

Edward Tolman Biography

Edward Chace Tolman was born in Newton, Massachusetts in 1886. Although his father wanted him to continue the family business, Tolman decided to study electrochemistry; However, after reading William James he discovered his vocation for philosophy and psychology, a discipline to which he would end up dedicating himself.

He graduated in Psychology and Philosophy from Harvard Shortly after, he moved to Germany to continue training on his way to a doctorate. There he studied with Kurt Koffka; Through him she became familiar with Gestalt psychology, which analyzed perception by focusing on the overall experience rather than on separate elements.

Back at Harvard, Tolman investigated the learning of nonsense syllables under Hugo Münsterberg, a pioneer of applied and organizational psychology. He earned his PhD with a thesis on retroactive inhibition a phenomenon that consists of the interference of new material in the retrieval of previously learned memories.

After being expelled from Northwestern University, where he worked as a professor for three years, for publicly opposing American intervention in World War I, Tolman began teaching at the University of Berkeley in California. There he spent the rest of his career, from 1918 until his death in 1959.

Theoretical contributions to Psychology

Tolman was one of the first authors to study the cognitive processes from the framework of behaviorism ; Although it was based on behaviorist methodology, he wanted to demonstrate that animals could learn information about the world and use it flexibly, and not only automatic responses to certain environmental stimuli.

Tolman conceptualized cognitions and other mental contents (expectations, objectives…) as intervening variables that mediate between the stimulus and the response. The organism is not understood as passive, in the manner of classical behaviorism, but rather it actively manages information.

This author was especially interested in the intentional aspect of behavior, that is, in goal-oriented behavior; thus Their proposals are categorized as “propositional behaviorism.”

The EE and ER learning models

In the mid-20th century there was a deep debate within the behaviorist orientation around the nature of conditioning and the role of reinforcement. Thus, the Stimulus-Response (SR) model, personified by authors such as Thorndike, Guthrie or Hull, and the Stimulus-Response (EE) paradigm, of which Tolman was the most important representative, were opposed.

According to the EE model, learning occurs through the association between a conditioned stimulus and another unconditioned stimulus, which evokes the same conditioned response in the presence of reinforcement; On the other hand, from the ER perspective it was defended that learning consists of the association between a conditioned stimulus and a conditioned response

Thus, Tolman and related authors considered that learning depends on the subject detecting the relationship between two stimuli, which will allow him to obtain a reward or avoid a punishment, compared to the representatives of the ER model, who defined learning as the acquisition of a conditioned response to the appearance of a previously unconditioned stimulus.

From the ER paradigm, a mechanistic and passive vision of the behavior of living beings was proposed, while the EE model affirmed that the role of the learner is active since it implies a component of voluntary cognitive processing, with a specific goal

Experiments on latent learning

Hugh Blodgett had studied latent learning (which does not manifest itself as an immediately observable response) through experiments with rats and mazes. Tolman developed his famous proposal on cognitive maps and much of the rest of his work based on this concept and the work of Blodgett.

In Tolman’s initial experiment three groups of rats were trained to navigate a maze In the control group, the animals got food (reinforcement) when they reached the end; On the other hand, the rats in the first experimental group only got the reward from the seventh day of training, and those from the second experimental group only got the reward from the third day.

Tolman found that the error rate of the rats in the control group decreased from the first day, while those in the experimental groups did so sharply after the introduction of food. These results suggested that the rats learned the route in all cases, but only reached the end of the maze if they expected to receive reinforcement.

Thus, this author theorized that the execution of a behavior depends on the expectation of obtaining reinforcement but nevertheless the learning of said behavior can occur without the need for a reinforcement process to occur.

The study of cognitive maps

Tolman proposed the concept of cognitive maps to explain the results of his and Blodgett’s experiments. According to this hypothesis, The rats constructed mental representations of the maze during training sessions without needing reinforcement, and therefore knew how to reach the goal when it made sense.

The same would happen with people during everyday life : when we repeat a route frequently we learn the location of a large number of buildings and places; However, we will only address them if it is necessary to achieve a specific goal.

To demonstrate the existence of cognitive maps Tolman did another experiment similar to the previous one, but in which after the rats learned the route of the maze it was filled with water. Despite this, the animals managed to reach the place where they knew they would find food.

In this way he confirmed that the rats they did not learn to execute a chain of muscular movements as the theorists of the ER paradigm defended, but rather that cognitive variables, or at least non-observable ones, were necessary to explain the learning they had acquired, and the response used to achieve the objective could vary.