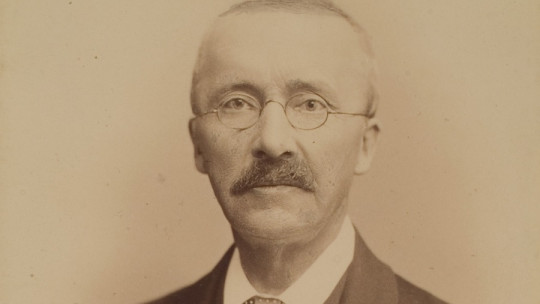

In 1873, Heinrich Schliemann, a Prussian archaeologist, was excavating in the area of Hisarlik, present-day Turkey. The idea that drove him was in his head since he was a child: to find the mythical Ilium, the Troy sung by Homer in his Iliadthe epic poem that had accompanied him since his earliest childhood.

On one of the days of work, Schliemann’s team discovered a treasure of incalculable value: a compendium of bracelets, rings, bracelets, diadems and other objects that the archaeologist immediately baptized as the “treasure of Priam”, the legendary king of Troy. But did the remains found by Schliemann really belong to Troy?

In this biography of Heinrich Schliemann we invite you to an exciting journey through the life of this adventurer and archaeologist who spoke no less than 15 languages and whose life was marked by the obsession he felt with ancient Greece.

Brief biography of Heinrich Schliemann

Heinrich Schliemann was born on January 6, 1822 in Neubukow, present-day Germany He was one of the nine children of the Protestant pastor Ernst Schliemann and his wife Teresa Louise Sophie. His father was an alcoholic and constantly abused his wife, so little Heinrich lived a stormy childhood. When he was only nine years old, his mother died from complications during her ninth childbirth, and Ernst definitively ignored his children. The children then go into the care of uncles.

However, in the midst of this gray childhood, a light was lit that would accompany him throughout his life: his passion for ancient Greece. This passion was awakened when he was 7 years old; according to what he says in his Autobiographypublished in 1869, on Christmas 1829 his father gave him the Universal History for children, a work that at that time was considered suitable for the historical instruction of children. Schliemann was especially impressed by the engraving depicting Aeneas, the hero of Troy, escaping the burning of the city with his elderly father Anchises on his back.

Later, when he was already working in a store to earn his bread, He listened in amazement as a drunk customer recited Homer in Greek Schliemann himself confesses that he did not understand a word, but that that night he remembered the Homeric stories that his father told him, and that then he wished with all his might to be able to learn, one day, the language. of Homer.

His time of youth

The continuous hours of work in the store did not leave the young Schliemann time to dedicate himself to what he liked most: studying. Determined to amass a great fortune to be able to indulge his passion , left for Venezuela in search of a new life. However, bad luck followed him. His ship was wrecked off the coast of the Netherlands; Schliemann and some companions were miraculously saved by getting into lifeboats, which left them safe and sound on the coast.

But nothing represented a serious obstacle for the incombustible Heinrich Schliemann. A little later we find him in Hamburg, where he works in a commercial office stamping bills of exchange and carrying the mail. His work situation does not seem to have changed much, since the hours are still hellish, but Schliemann manages to find time to study. At 22 years old, the young man already speaks seven languages which would increase to the astonishing figure of fifteen just ten years later.

The businessman Schliemann

His success with languages opens the doors for him to dedicate himself to various businesses, which begin to bring him a great fortune. Shady business, we could say; because Schliemann has no qualms about trading in weapons and black market products, taking advantage of the commercial blockade caused by the Crimean War (1853-1856).

Be that as it may, Already possessor of an immense fortune, in 1866 he settled in Paris with Ekaterina Petrovna Lishin , whom he had married four years before, and began his studies in Antiquity Sciences and Oriental Languages at the Sorbonne. Having solved the economic issue, which for so many years was his main goal, Schliemann’s lively curiosity can now focus on his eternal passion: ancient Greece.

The “Schliemann method”

How was Heinrich Schliemann able to learn so many languages in such a short time? We have already said that, at the age of 33, he mastered no less than fifteen languages, including Russian, Greek and Arabic. It is clear that he started from a privileged mind like few others, but it is also true that Schliemann developed his own learning method that, surprisingly, is still valid today

We find the first testimony of this method in the prologue of Ithacathe book he wrote in 1869. Later, he recovered it in his Autobiography. According to Schliemann, his method was simply based on “reading aloud a lot, not doing translations, spending an hour each day, always writing down elaborations on topics that interest us, improving them under the supervision of the teacher, and memorizing and reciting the next day. that you improved and recited the day before.” In short, Schliemann was truly self-taught.

The “Schliemann method” became tremendously popular In 1891 it appears Schliemann method for self-learning of the English languagewhich was followed by two more editions, one in 1893 and another in 1910. Stefanie Samida collects, in her text The Schliemann method for self-learning languages, the article that the book’s editor, Paul Spindler, published on January 3, 1891, where he says that “Schliemann learned Greek by reading Homer. What an individual can do can be applied to mass instruction; This can be applied to school instruction.” In other words, Spindler called for the “Schliemann method” to be introduced in German schools.

Greece, always Greece

Sing, oh goddess, the anger of pale Achilles; fatal anger that caused infinite harm to the Achaeans and precipitated many brave souls of heroes into Hades, whom it made prey to dogs and food for birds…

This is how one of the most famous epic stories of all time begins: The Iliad, supposedly written by the Greek poet Homer in the 8th century BC We say “supposedly” because the truth is that we have no record of this author beyond the vague references that some authors provide us with. Thus, Herodotus, in his storiesplaces the poet in the year IX BC, which would make him more or less contemporary with the Trojan War.

Today the existence of the poet is questioned, and some historians maintain that, in reality, Homer never existed, and that it is the name under which a very ancient oral tradition is recorded in writing. Be that as it may, there is no doubt that the Iliad and the Odyssey They are the two great epic stories of Western civilization, which have fascinated artists and writers since time immemorial.

Heinrich Schliemann was convinced that the Troy of Homer had existed , and that only the Homeric texts were enough to find it. Of course, the obstinacy of the already archaeologist (he had received his doctorate in 1869) was harshly discredited by his colleagues. How could an epic poem of dubious historical rigor be established as a basis for serious archaeological studies? But, at this point, it is clear to us that Schliemann’s stubbornness in pursuing his dreams was as harsh as the criticism he received. Indeed, in 1868 we found him already in Greece, exploring the territory.

The following year, the same year in which he received his doctorate, he divorced Ekaterina and married Sophia Engastromenos, a young Greek woman 30 years younger than him. This woman’s face has been immortalized for posterity in the famous photograph of 1873, in which she shows off the jewels from Priam’s treasure, as if she were a new Helen. In 1871, the couple’s first daughter, Andromache, was born, and in 1878, Agamemnon was born names that demonstrate Schliemann’s obsession with the Greek epic.

But did this indomitable adventurer discover the city of the Homeric song? Did he finally manage to silence all those who mocked his naivety?

The “treasure of King Priam”

His colleague Frank Calvert, British consul for the Dardanelles, had told him about the possibility that the mythical city was located in Hisarlik, where he had previously been excavating. Schliemann never mentioned Calvert in his memoirs, even though it was Calvert who suggested he excavate in this territory. Perhaps Schliemann thought that the find was too important to share the spotlight… Because it was in Hisarlik that Schliemann’s team found (following methods that some experts call dubious, to say the least) a treasure of incalculable historical value: cups, rings, bracelets and tiaras, the same ones Sophia wore in the famous photograph, taken the same year of the discovery.

Heinrich Schliemann was overjoyed: he declared that had found none other than the treasure of Priam, the legendary king of Troy

It seems that the archaeologist had not abandoned his unscrupulous methods, since he immediately secretly took the magnificent pieces to Greece. This smuggling earned him a severe reprimand from the Ottoman government, which forced him to pay a fine for theft of national property… genius and figure, you know.

Face to face with Agamemnon

The excitement of the discovery of the supposed Troy had encouraged Schliemann to continue investigating. In 1876 he was again in Greece and excavating in Mycenae, where the Achaeans of the Iliad were supposed to have come from, led by their king Agamemnon. Luck was once again on the archaeologist’s side: soon, his team discovered half a dozen royal tombs In one of them (which they called tomb V), a gold death mask appeared. Schliemann was overjoyed. He had found King Agamemnon’s funerary mask!

But no, it was not Agamemnon’s face that Schliemann had before his eyes. Later it was discovered that the mask belonged to a time much earlier than that of the supposed king of Mycenae, so the Prussian theory inevitably fell to the ground. In any case, the mask constitutes one of the most important pieces of the Greek archaic period, both for its technical quality and for its dazzling beauty. It is currently kept in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens and is, without a doubt, one of the main attractions of the museum.

Criticized by some, praised by others

Schliemann’s archaeological work did not stop with the discovery of the “mask of Agamemnon.” During the last years of his life he continued excavating in various parts of Greece, where he made notable finds. His death surprised him when he returned to his beloved Athens from Paris. A severe ear infection, which had spread to the brain, ended his life on December 26, 1890, at the age of 62 His remains rest in a splendid mausoleum in the Greek capital, just as he would have wanted.

His work as an archaeologist was harshly criticized during Schliemann’s own lifetime. And these criticisms were not without reason, since it cannot be denied that his methods were, at the very least, unorthodox. In fact, Some of the interventions by Schliemann’s team (reportedly carried out with dynamite) seriously and irreversibly damaged some of the strata of the excavations. On the other hand, there are voices that consider Heinrich Schliemann the first modern archaeologist. And, in fact, subsequent research has ended up proving him right, at least in part. The work that has continued to be carried out in Hisarlik has brought to light the various strata of a city (no less than nine in total) among which, according to archaeologists such as Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940), the mythical city of the poem could be found. Homeric.

This archaeologist was part of Schliemann’s team and continued his work after his death. Between 1893 and 1894 he discovered that the stratum called “Troy VI” appeared to have been destroyed by a great fire. Could this “Troy VI” be Homer’s Ilium?

Like almost all the characters in the story, Heinrich Schliemann’s life is dotted with lights and shadows. It is true that his methods were more than debatable, and it is even more true that the fortune he used to carry out his excavations was not the result of very “clean” businesses. But, on the other hand, his undeniable passion and extraordinary perseverance deserve, at the very least, applause. Heinrich Schliemann will always be linked to Troy and Homer’s Iliad. As he himself said in his memoirs: “I thank God because he has never abandoned my firm belief in the existence of Troy.”