Broadly speaking, anthropology is the science that studies human beings within a community. It emerged at the end of the 19th century and, as happens with most disciplines that cover a very broad area of knowledge, it soon split into various branches that sought to perfect the object of their study.

Today we are going to talk about psychological anthropology, the most recent branch of anthropological studies

What is psychological anthropology?

Psychological anthropology is the branch of anthropology that studies the relationship between human psychology and individual behavior within sociocultural structures

Its main objective is to discover the common behaviors in all human beings, beyond the cultural realities that surround them. To do this, psychological anthropology combines elements of anthropology itself with elements from psychology studies, such as, for example, psychoanalysis.

It is necessary to establish what the main differences are between anthropology and psychology. Broadly speaking, we can say that, while the first is dedicated to study of the human being as an element inserted in a community psychology usually focuses on the study of the human being as an individual.

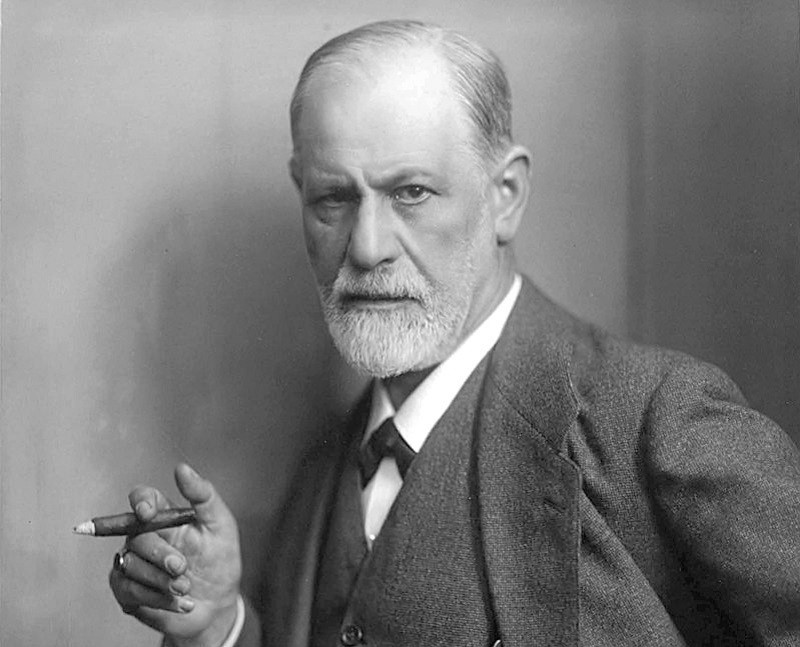

However, at the beginning of the 20th century some anthropologists realized the possibilities offered by combining anthropology studies with the new theories of psychoanalysis, developed by a certain Sigmund Freud. Let’s see it below.

The origin of psychological anthropology: criticism of Sigmund Freud

In 1913 it appears Totem and tabooone of Sigmund Freud’s first works, whose striking subtitle Some concordances in the mental life of savages and neurotics revolutionized the panorama of anthropology, by including psychoanalysis in the study of cultures. The central idea of this essay (now widely surpassed) is that a kind of analogy between the development of primitive communities and the psychic development of the individual

The main thesis of the work revolves around the emergence of the totem and the taboo, whose origin Freud places in the tyranny of an “alpha male” whom the rest of the men in the community would hate and whom, finally, they would murder, with the feeling of guilt that the act would entail afterwards.

Such a theory was highly revolutionary for the time (we are talking about 1913), and it did not take long for criticisms of Freudian postulates In these criticisms we must locate the origin of psychological anthropology.

For example, Franz Boas (1858-1942), a distinguished American anthropologist of German-Jewish origin, was extraordinarily critical of Freudian psychoanalysis, despite the fact that he himself was interested in psychology. No less critical was Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) who, in his work The sexual life of the savages of northwestern Melanesia (1929), criticized the universality of the Oedipus complex, which Freud had claimed so much.

@image(id)

Through data extracted through field studies, Malinowski demonstrated that this complex, according to which the child desires the “death” of the father in order to have access to the mother, It did not occur in all cultures The basis of this British anthropologist’s criticism is that the Oedipus complex, as proposed by Freud, needed a patrilineal monogamous family structure to develop, something that obviously does not occur in all cultures in the world.

In any case, it cannot be concluded that Malinowski, as well as other anthropologists who were critical of psychoanalysis, were completely against its use in the anthropological field; rather what they intended is that the social and cultural realities of different human communities be taken into account They were clear that psychoanalysis could be very useful for anthropology; Freud’s mistake had been, mainly, to start from a strict and essentially European vision and make it extendable to the rest of the world.

In short, we can conclude that, although there were already certain pre-Freudian currents that claimed the union between psychology and anthropology, it was not until the appearance and dissemination of Freud’s ideas that this current became generalized, precisely through the criticism of his works.

Universal principles… do they exist?

We have already commented at the beginning that one of the objectives of psychological anthropology is to discover common behaviors in human beings, regardless of the culture in which they are immersed. Throughout the 20th century, many anthropologists investigated and carried out numerous field studies to unravel whether, indeed, certain common behaviors could be extracted that were a product of the human psyche rather than the culture in which the individual moved.

Margaret Mead (1901-1978), in her studio Coming of age in Samoatried to clarify If the famous adolescent rebellion was common in all cultures or if, on the contrary, it was a particularly Western phenomenon. The result was surprising: Samoan adolescents did not experience this period in such a traumatic way, among other things, because from a young age they were talked openly about death or sex. Apparently, this more “natural” relationship with the world prevented inhibitions and doubts from being created in the child or, at least, from forming in the same quantity as a Western adolescent. Mead’s study, which asked about the universality of adolescence, is a very clear example of where psychological anthropology intends to go.

In general, the first psychological anthropologists agreed with Freudian proposals that maintained that the bases of psychic development occur in childhood. To this they added the capital importance that culture has in the entire process Thus, throughout the 20th century, studies were carried out that conscientiously analyzed all the stages of this human period (breastfeeding, weaning, rivalry between siblings…) and, above all, how they developed in the various cultural manifestations.

Anthropology and psychology finally shake hands

The apparent rivalry between anthropology and psychology and the disagreements that had taken place in the first decades of the 20th century had a “happy ending” in 1937, when, at Columbia University (USA), they began to teach interdisciplinary seminars that tried to unite both sciences for effective collaboration Abraham Kardiner (1891-1981), who combined notions of psychiatry and anthropology, played a great role in this meeting.

Kardiner had personally met Sigmund Freud in Vienna in the 1920s, so his contact with psychoanalysis had been intense. He became keenly interested in how human personality was constructed and, above all, in how culture and personality were related. Aware of the need to unite both disciplines, in 1937 he created the aforementioned seminar, with the aim of reaching conclusions jointly. Some anthropologists who worked together with Kardiner were Ruth Bunzel (1898-1990), who carried out, among others, a comparative study of alcoholism in Guatemala and Mexico, Cora du Bois (1903-1991) and Ralph Linton (1893-1953).

The essential thing in Abraham Kardiner’s work is that he applies the technique of psychoanalysis to the results obtained through anthropological field work. Kardiner distinguished between “primary institutions” and “secondary” ones; The first would be, for example, subsistence techniques and family organization, while the second would be made up of elements such as religion or art. Both one and the other would profoundly influence the child and mark the development of his personality and the changes made in the primary institutions would mean a change in the secondary ones.

The new era of psychological anthropology

In the 1950s something was changing. The methodology used by followers of Abraham Kardiner was subjected to a number of criticisms, and authors such as John Whiting and Irvin Child expanded Kardiner’s theory of institutions.

In this period the idea that culture “manufactures” homogeneous personalities is discussed ; For example, according to the anthropologist Anthony Wallace (1923-2015), the cultural system only organizes the different personalities that make it up. Thus, the men and women who make up a cultural reality would not have to share ideas, beliefs and emotional structures, and the only thing that is shared, then, is what he calls “institutional contract.”

Currently, and despite being the most recent branch of anthropology, psychological anthropology is booming and offers great possibilities for study. Today’s anthropologists are very far from thinking that the cultural phenomenon can be separated from individual aspects such as the human psyche, and this, which at the time may have seemed complex, dark and even contradictory, is now a fascinating future full of odds.