Currently, we have a very specific idea of what nationalism is. We could define it as the feeling of belonging to a community, identified as a nation, in which the individual is immersed and with which they share essential characteristics for their identity such as language, tradition, religion, ethnicity and culture, among many. others.

But was it always like this? What are the origins of nationalism? Next, we will briefly review nationalism and its history, and tell how it has developed over the centuries.

Since when has nationalism existed?

Even if it looks like a lie, nationalism is not as old as we may initially think In fact, he has a clear date of birth: the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century; more specifically, 1814, the year in which the Congress of Vienna was held after the defeat of Napoleon. We explain ourselves better below.

The birth of liberalism

Until the end of the 18th century, what has been called the Old Regime had prevailed in Europe, a model of government based on a strict hierarchy of society and led by absolutist monarchies in which the monarch was the head of the state and was legitimized by God. . This Old Regime, which has its origins in the strengthening of the European monarchies of the Modern Age (and not, as is often believed, in the Middle Ages) did not grant, logically, any power to the people.

It was not until the American War of Independence (with the writing of the first constitution) and, above all, with the arrival of the French Revolution, that the political and social landscape began to change. From then on (although not without difficulty and resistance) power will rest in the citizen, giving way to the so-called popular sovereignty. Citizens therefore acquire a new power and meaning, they will be aware of their importance in the future of history and will create new political, social and ideological models.

It is then, and only then, that the concept of nation arises. Not before. As we can see, the idea is very recent; It is barely two hundred years old. Until then, we could find communities that identified with a specific region or city; but it was a vague idea, much more linked to family roots, birth or marriage. The concept of nation, as we will see in the next section, has very specific characteristics that begin with the birth of liberalism and constitutional monarchies at the end of the 18th century.

The Congress of Vienna and the new European reality

We have established the year 1814 as a key date to understand the birth of nationalism, when the Congress of Vienna began in Europe. It is the year of Napoleon’s defeat which, during the immediately preceding years, has spread panic on the continent. The Napoleonic invasions have a lot to do with the nationalist sentiment that begins to overwhelm the inhabitants of the invaded countries: The Spanish people take up arms against the French invader and categorically reject Joseph Bonaparte, a “foreign” king

Likewise, during this period the Spanish colonies in America began to be aware that they had a different identity from the metropolis. Something similar happens in Russia, which sees its national identification strengthened through the war with the French.

We have, therefore, a Europe contrary to French expansion that, in its titanic resistance, creates one of the first centers of nationalism (incidentally, romanticized and idealized by later historiography). On the other hand, the aforementioned Congress of Vienna, which aims to reestablish the European borders prior to the Napoleonic invasions, further shakes the spirits of the troubled countries that, after the war and after the expansion of the ideals of the French Revolution, They have begun to acquire national identities.

What role did the Congress of Vienna have in reinforcing nationalism? In the Old Regime, borders were designed through wars and pacts between the reigning dynasties ; That is, they were not based on any national reality. During the Congress of Vienna, the different European monarchies attempted to reestablish these borders inherited by their ancestors, which had been temporarily suppressed by Napoleon’s attempt to establish a French empire.

However, the French Revolution has brought new ideas of “citizen”, “popular sovereignty” and “nation”. The people no longer constitute the group of subjects of a monarch; Now they are citizens with full rights and with participation in the future of the state. Likewise, the Napoleonic invasions have awakened a clear national consciousness. The people warn that the only possible state model is the one based on “organic” borders, that is, on the very nature of the people. Since then, The border criterion will no longer rest (at least, in theory) on the capricious will of the rulers , but on cultural, ethnic and identity bases. Some bases that, by the way, do not always correspond to reality, as we will see.

The concept of nation

The concept of nation is so recent and has such specific characteristics that, in fact, we know which authors “invented” it or, at least, put it on paper. These are the German philosophers Johann Gottfried Herder and Johann Gottlieb Fichte, who, at the beginning of the 19th century, clearly outlined what these characteristics were.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814) wrote in 1808 his famous Speeches to the German nation, in which the roots of the German nation were laid. These roots were based on two fundamental pillars: on the one hand, language and, on the other, the existence of a glorious past.

In the case of the German nation, the language was, of course, German, which at that time was spoken in several European states (Germany was not yet unified). That is to say, According to Fichte’s criterion, any community that spoke German was part of the same nation , regardless of the fact that these communities were not united by a state legal framework. In this way, the basis is laid that the nation is absolutely independent of the state, and that state borders do not always correspond to national borders.

On the other hand, the ancient deeds of the Germanic peoples, those who invaded the Roman Empire, become a kind of lost arcadia, a glorious past in which the German people see a model to follow. It is then that a feverish search for the origins of the “German homeland” begins, spurred by the newborn Romanticism. The Brothers Grimm were notable figures in this sense, since, through their compilation of German stories, on the one hand, and their German grammaron the other hand, contributed to laying the foundations for a supposed origin and a common folklore.

Thus, we have two fundamental pillars on which the concept of nation is built since the 19th century. One, the language; two, the common past, usually idealized or even directly invented.

Romanticism and nationalism

Nationalism cannot be understood without the romantic movement, since it was within the framework of Romanticism that the first developed and reached its highest levels of exaltation and idealization.

We have already seen how much German Romanticism had to do with the birth of German nationalism. Philosophers like Fichte and Herder, but also writers like Goethe and composers like Wagner (the latter through his operas based on German mythology), built the foundations of what would later become the German nation. As a consequence of all this, The idea arises that Germany, as a nation, should be united under the same political framework This is important, since, for nationalism, a nation has the right to govern itself and establish a state.

Thus, in the middle of the 19th century, German unification took place, which placed the German-speaking countries under the same state, with the significant exception of Austria, predominantly Catholic compared to German Protestantism. Around the same time, the Risorgimento Italian lays the foundations for the unification of the Italian Peninsula and the birth of the kingdom of Italy.

And while some nations that were scattered united, others that were annexed to states with which they did not identify fought for their independence. This is the case of Greece, which in 1830 became independent from the Ottoman Empire, and Belgium, which, the following year, managed to establish itself as an independent state. At the base of all this there coexists a more or less realistic national consciousness, based on language, history and traditions, with a strong idealization that often invents connections and common characteristics to justify its ideas

Nationalism and historical distortion

Romanticism is the era par excellence of national idealization, and also (it must be said) of national invention. Romantic historians tend to distort history and convert episodes that have nothing to do with nationalism (basically, because they predate the emergence of the concept) into moments of national struggle. These historical myths have persisted to this day, partly because many political regimes have been interested in maintaining them, partly because, sometimes, by repeating a speech, invention and reality become confused

This is the case of Rafael Casanova, elevated by nineteenth-century intellectuals as a myth in the Catalan nationalist struggle, and who, however, was nothing more than a standard bearer of the Austrian cause within the framework of the War of Succession. Likewise, we find in Spain in the 19th century a strong idealization of the “Reconquista”, with a clear tendency to demonstrate in a “historical” way the existence of Spain as a nation before the arrival of the Muslims, when this concept did not exist.

The term Hispania It was a geographical term that the Romans already used. In the Middle Ages we find documents, such as The book of feyts by Jaume I (The book of the acts of Jaume I), where the word Spain is collected. However, we should not interpret it from a current meaning of the word, since although its use was common in the medieval centuries, It served to designate the Christian kingdoms in front of the Muslim territory, and in no case did it have a nationalist connotation

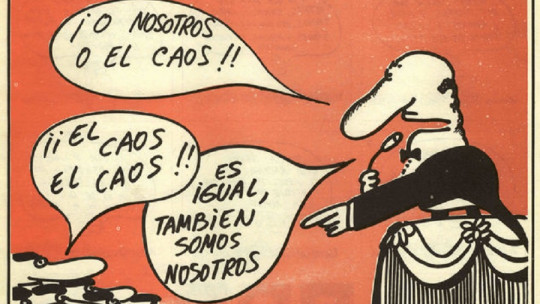

Historical distortion is the basis of totalitarian movements, which gives us an idea of the danger entailed by ignorance of the past. Nazi Germany relied on the ideas of the German nation that emerged in the 19th century and took them to their ultimate consequences; On the other hand, Mussolini’s Italy was based on Rome’s glorious past and the importance of its recovery to create a powerful Italy superior to the rest of Europe. Likewise, the Franco regime adopted episodes from Spanish history and turned them into founding myths that reinforced its ideology.