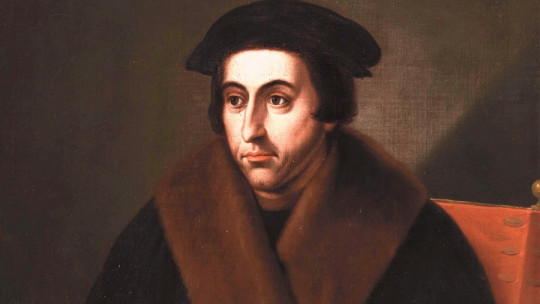

Thomas More was an English humanist thinker who witnessed the founding of the Church of England, an institution that by simply opposing it would mark the beginning of its end.

Considered a martyr and saint by the Catholic Church, the figure of this theologian has greatly influenced the humanism of the 16th century, deeply affecting the Catholic world. His criticism of tyranny and his defense of the Catholic faith caused the Vatican to even grant her a holiday in his honor.

Below we will go into more depth about the life and work of this intellectual through a biography of Thomas More in which we will see, among other things, how he thought, what his relationship was with King Henry VIII of England and what great figures of his time he rubbed shoulders with.

Brief biography of Thomas More

Thomas More, in Spanish Thomas More and in Latin Thomas Morus, venerated by Catholics as Saint Thomas More, He was an English thinker, theologian, politician, humanist and writer In addition to having published works in which he addressed religious and legal aspects, he is also credited with having written several poems, since he was a man of artistic concerns. He served as Lord Chancellor to Henry VIII and also taught law and worked as a judge of civil affairs.

Among his most notable works we have “Utopia”, a text so important that it has been considered the precursor of the utopian genre in the modern novel. It is a text that describes what a perfect country, an ideal society, would be like. In addition to this text, several books are also famous in which he was harshly critical of the new ideas about Christianity promoted by Martin Luther and William Tyndale.

Although he was initially a close friend of Henry VIII, His position against the nullity of the royal marriage and aversion to the Anglican reform would end up causing him to be prosecuted, accused of other treason against the king and for not having taken the anti-popish oath when the Church of England emerged.

He wanted the marriage with Catherine of Aragon to continue, and did not sign the Act of Supremacy in which full religious powers were given to the king. This would be what would take Thomas More to the grave, becoming a Catholic martyr.

Early years

Thomas More was born in the heart of London, England, on February 7, 1478 He was the eldest son of Sir John More, steward of Lincoln’s Inn, one of the four bar associations of the City of London, a jurist and later knighted and judge of the royal curia. His mother was Agnes More, née Graunger.

In 1486, after having completed five years of primary school at the ancient and prominent Saint Anthony’s School, he was taken to Lambeth Palace, following the custom carried out by good London families. There he served as page to Cardinal John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England, defender of the humanist ideas of the Renaissance.

John Morton ended up having a lot of esteem for the young Moro, trusting that he could develop his intellectual potential and that is why he decided in 1492 to suggest the admission of Thomas More to Canterbury College of the University of Oxford, when the young man was barely fourteen years old. There he would spend two years studying scholastic doctrine and perfecting his rhetoric, being a student of English humanists such as Thomas Linacre and William Grocyn.

early adulthood

Despite the above, Thomas More ended up leaving without graduating and, at the insistence of his father, he dedicated himself to studying law in 1494 at the New Inn in London. He would later do so at Lincoln’s Inn, where his father had worked. Shortly after, he would begin to practice law before the courts and it would be at this time that he would learn French since it was necessary to work in the English courts of justice and practice diplomacy.

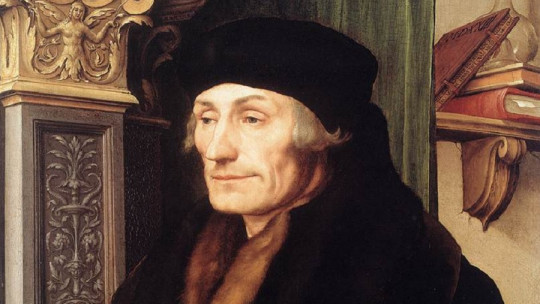

In 1497 he began to write some poems, which were done with intense irony, something that earned him some fame and recognition. In fact, thanks to this, he would have his first encounters with the precursors of the Renaissance, meeting Erasmus of Rotterdam himself and John Skeleton. Thomas More and Erasmus would end up establishing a very strong friendship.

When 1501 arrived, Moro entered the Third Order of Saint Francis, living as a layman in a Carthusian convent until 1504, although he took advantage of those years to dedicate himself to religious study. At this time he translated various Greek epigrams into brass and commented on “De civitate Dei” by Saint Augustine of Hippo.

Thanks to several English humanists he was able to have contact with Italian Renaissance ideas and arts knowing the figure of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, whose biography he translated in 1510. Although he would end up leaving his ascetic lifestyle, it is worth saying that from this time he would retain some acts of penance, wearing a hair shirt on his leg all his life and practicing occasionally flagellation.

Upon leaving the Carthusian convent in 1505, he married Jane Colt, and his daughter Margaret was born that same year. In 1506 his second daughter, Elizabeth, would be born, in 1507 his third, Cicely, would be born, and in 1509 his son John would be born. By leaving the Carthusian order behind he was able to practice law successfully, thanks to his concern for justice and equity and his extensive knowledge of law. He later became a civil litigation judge and law professor.

In 1506 he translated Lucian of Samosata into Latin with the help of Erasmus. At that time he was a boarder and butler at Lincoln’s Inn, where he lectured between 1511 and 1516. He also participated in negotiations between large companies in London and Antwerp, Flanders and I would learn firsthand many of the views widespread on the continent about the nature of man and what a sovereign should be like respectful of the people.

In 1510 Thomas More was appointed Member of Parliament and Deputy Sheriff of London, although this joy would be overshadowed by the death of his wife Jane a year later. Even so, found the strength to marry Alice Middleton a widow seven years older than him and with a daughter, little Alice.

Political life

Being a member of parliament since 1504, Thomas More was elected judge and sub-prefect in the city of London and began to express his opposition to some measures imposed by Henry VII. With the arrival of Henry VIII, son of the previous king, seen as a “protector of humanism and the sciences”, Thomas More joined the first Parliament convened by the king in 1510.

Moro traveled through Europe and received influences from different universities. In fact, It would be on his travels around the continent that he would write his poems for the newly crowned king , poetry that would reach the hands of the new monarch who called him. Thus a strong friendship would be born between the two, although not unbreakable.

Between 1513 and 1518 he wrote his “History of King Richard III” written in Latin and English, although he could not finish the version in his native language and it ended up being printed in English imperfectly in Richard Grafton’s “Chronicle” (1543). This text would be used by other chroniclers of the time, such as John Stow, Edward Hall and Raphael Holinshed, thus transmitting material that would later be used by the famous William Shakespeare in his dramaturgical work “Richard III”.

In 1515, Thomas More was sent with a commercial embassy to Flanders, and that same year he wrote “Utopia.” , the full version of which was first published in Leuven. In 1517 he went to work for King Henry VIII and was appointed “Master of requests”, becoming a member of the Royal Council. The king used his diplomacy and tact, trusting the figure of Thomas More in some of the most important diplomatic missions to all types of European countries.

In 1520 he helped Henry VIII write “Assertio Septem Sacramentorum” (“Defense of the Seven Sacraments”). This was followed by the appointment of him to different positions and the decoration of him with different honorary titles. In 1521 he was knighted and appointed vice-chancellor of the Exchequer. That same year his eldest daughter, Margaret, would marry William Roper who would be the first biographer of Thomas More.

In 1524 he was appointed “High Steward”, the title of censor and administrator of the University of Oxford, an institution of which he had been a student. In 1925 he would also receive such an honor from the University of Cambridge and chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. In 1526 He became the judge of the Star Chamber and moved his residence to Chelsea where he would write a letter to Iohannis Bugenhagen in which he explicitly defended papal supremacy.

In 1528 the bishop of London allowed him to read heretical books with the intention of refuting them, in order to prevent new and dangerous Lutheran ideas from undermining the power of the Holy See in Anglican lands. Finally, in 1529 he was appointed Lord Chancellor, the first lay chancellor for several centuries.

However, despite being a layman and faithful to the king, he was even more faithful to the pope and the Catholic faith, starting the controversy in 1530. That year a letter of names and prelates was published in which the pope was requested to annul the marriage. royal between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, a letter which More refused to sign. This naturally caused the relationship between the king and the thinker to change and earned the enmity of Henry VIII.

In 1532 he resigned his position as chancellor and two years later he refused to sign the Act of Supremacy, which declared the king as the highest head of the new Church of England. This Act established the sentence for those who did not accept it, and on April 17 of the same year Moro ended up being imprisoned

Campaign against the Reform

Thomas More saw the Protestant Reformation as a full-fledged heresy that threatened the unity of church and society. His early actions against the Reformation included helping Cardinal Wolsey dispose of Lutheran books that had been smuggled to England. He also dedicated himself to spying on and investigating suspected Protestants, especially publishers, and arresting anyone who was in possession, transporting or selling books that advocated the Protestant Reformation.

Given his actions, it is not surprising that rumors circulated, both during his life and after his death, that spoke of all types of mistreatment of heretics when he served as Minister of Justice. Criticism came from many anti-Catholics, including John Foxe alleging that More frequently used torture and violence when interrogating alleged heretics.

During his period as chancellor, six people were burned at the stake for heresy: Thomas Hitton, Thomas Bilney, Richard Bayfield, John Tewkesbery, Thomas Dusgate and James Bainham. Burning heretics at the stake was almost a tradition at the time. In fact, around thirty bonfires had burned in the century before More served as chancellor, and they continued to be used by both Catholics and Protestants during the turbulent times of Europe in the midst of religious reform.

Nevertheless, Historians are very divided regarding the religious actions that More carried out as chancellor Some biographers, such as Peter Ackroy, attribute to him a moderate and even tolerant position in the fight against Protestantism. Others, like Richard Marius, are more critical, maintaining that More himself promoted the extermination of Protestants, ideas clearly contrary to his supposed humanist convictions.

Another case is that of Peter Berglar. Berglar indicated that during the twelve years of Thomas More’s influence as vice-chancellor of the Exchequer (1521), speaker of the House of Commons (1523), chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (1525), judge of the Star Chamber (1526 ), advisor to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey on numerous matters until his appointment as Lord Chancellor on 26 October 1529, not a single death sentence was pronounced for heresy in the diocese of London.

Instead, It was during the fall from grace of Thomas More shortly before his resignation as Lord Chancellor that the executions of heretics began attributed to the influence of John Stokesley, new bishop of London and leader of the newly founded Church of England.

Condemnation and death

As we mentioned, King Henry VIII fell out with Thomas More due to disagreements about the validity of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Tomás, as Chancellor, supported the union going ahead and was not in favor of nullity. Henry VIII had asked the pope not to consider his marriage to Catherine, and the refusal marked the beginning of England’s break with the Church of Rome proclaiming the king as head of the Church of England.

The reason behind all this was Henry VIII’s desire to have a male child, something that the already elderly Catherine of Aragon could not conceive. The annulment of the marriage would have erased Henry’s infidelity with Anne Boleyn, and would have legitimized the children he could have had with her. Had the royal marriage been annulled, the matter would have remained simply an anecdote, perhaps with some diplomatic disagreement between England and Spain but little more.

However, between the papacy not granting the annulment and Thomas More being against accepting some of the king’s wishes, tempers ended up becoming very heated. Henry VIII strongly alienated Thomas More and, after breaking with Rome and seeing that More refused to pronounce the oath that recognized Henry as supreme head of the Church of England, the monarch ordered the theologian to be imprisoned.

Finally The king, very angry, ordered More to be tried, who ended up being accused of high treason and sentenced to death Other European leaders, admirers of the great thinker who was More, among them the Pope and the Emperor Charles I of Spain and V of the Holy Empire asked that his life be spared, but they had no luck. Thomas More would be executed by beheading on Tower Hill a week after being condemned, on July 6, 1535 at the age of 57.

Despite its unjust and sad ending, it must be said that the death of Thomas More is somewhat curious. Even knowing that he was going to lose his mind, this did not make him lose his particular sense of humor , above all fully trusting in the merciful God who would receive him when he crossed the threshold of death. While he was climbing the scaffold he addressed the executioner and said:

“I beg you, I beg you, Mr. Lieutenant, to help me go up, because when I go down I will already know how to take care of myself.” After kneeling he said: “Notice that my beard has grown in prison; That is, she has not been disobedient to the king, therefore there is no reason to cut her off. Let me take you away.” Finally, he left his irony aside and addressed those present: “I die being a good servant of the king, but of God first.”

Outstanding works

Thomas More’s masterpiece is, without a doubt, “Utopia” (1516), a book that many have considered the precursor of the utopian novel genre, receiving its name from it. In this play addresses the social problems of humanity and exposes them in a perfect and idealized world, a nation that is located on an island with the name of Utopia Thanks to this text, More earned the recognition of all the scholars of Europe, having written it during one of his missions assigned by the king in Antwerp. Among his great inspirations was his close friend Erasmus of Rotterdam.

The other works are diverse, but always deal with common themes such as idealism and the condemnation of tyranny. Among them we have his “Life of Pico della Mirandola”, which as we have mentioned is a translation of the biography of this Italian humanist, who claimed the primacy of Plato over Aristotle. The figure of della Mirandola may not be very popular outside Italy, but thanks to Moro’s translation it has been able to have a certain impact in the rest of Europe.

There is also his “History of Richard III”, in which he ruthlessly criticized the tyrant king , who murdered his older brother and Edward IV’s young children to assume maximum power. He wrote this work in English and Latin, although the Latin version is much longer than the English one and has been erroneously attributed to Cardinal John Morton. More represents the character as a sad antihero, representative of political degeneration and tyranny.

He also composed some poems in English , highlighting tributes to the deaths of English queens and various epigrams from their youth, poems that emanate anti-absolutist thought. For More, the root of tyranny was found in greed, the desire for wealth and power, which feed and excite each other. Nor can one omit his dialogues and treatises in defense of the traditional faith, harshly attacking the reformists. We can find “Responsio ad Lutherum”, “A Dialogue Concerning Heresies”, “The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer” and “The Answer to a Poisoned Book”

In other books he delves into various spiritual aspects, having “Treatise on the Passion”, “Treatise on the Blessed Body” and “De Tristitia Christi”, the latter being a text written in his own handwriting in the Tower of London when he was imprisoned there. until his decapitation. It was later saved from the confiscation decreed by Henry VIII, a text which was passed at the will of his daughter Margaret to Spanish authorities and through Brother Pedro de Soto, confessor of Emperor Charles V, it ended up reaching Valencia in the hands of Luis Vives, a close friend. of More.

Canonization

For his fight for the Catholic faith, Thomas More was beatified along with 52 other martyrs, including John Fisher, by Pope Leo XIII in 1886 and was finally proclaimed a saint by the Catholic Church on May 19, 1935 by Pius XI. , originally establishing its festival on July 9. However, after a series of reforms in the mid-20th century, his festival was changed in 1970 to be celebrated on June 22. On October 31, 2000, Pope John Paul II proclaimed him patron saint of politicians and rulers

As surprising as it may seem, he is also considered a saint and a hero within the Christian Church of England, despite the fact that it was the founder of this institution, Henry VIII, who ordered his execution for precisely criticizing this new vision of Christianity. He is together with John Fisher among the group of martyrs of the reform and More is commemorated on July 6.