One of the scientific demarcation criteria is verificationism the idea that for something to be considered significant it must be empirically demonstrated or, rather, be able to be captured through the senses.

Over the years there have been several currents that could be considered in favor of this criterion of scientific demarcation, although it is true that they use their particular vision of what is understood as significant knowledge.

Next we are going to see what verificationism is, what historical currents could be considered followers of this idea and what differentiates it from falsificationism.

Verificationism: what it is, historical currents and falsificationism

Verificationism, also called the criterion of significance, is a term used to describe the current followed by those who are in favor of using the principle of verification in science , that is, maintaining that only statements (hypotheses, theories…) that are empirically verifiable (e.g., through the senses) are cognitively significant. That is, if something cannot be demonstrated through the senses, physical experience or perception, then it is a rather rejectable idea.

The criterion of significance has been a topic of debate among even those who say they feel verificationists, basically because many philosophical debates are made about the veracity of statements that are not empirically verifiable. verificationism has come to be used as a rule to demonstrate that metaphysical, ethical and religious statements are meaningless although not all verificationists consider that this type of statements are not verifiable, as would be the case of classical pragmatists.

1. Empiricism

Taking a historical perspective on the idea of verificationism, we can trace its earliest origins to empiricism, with figures such as the English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704). The main premise in empiricism is that the only source of knowledge is experience through the senses something that verificationism really defends and that, in fact, it could be said that the verification criterion is the consequence of this first empiricist idea.

Within empiricist philosophy, it was held that the ideas that circulate in our minds have to be the result of perception-sensation, that is, sensations that we have converted into ideas or it is also the combination of those same ideas obtained through experience. converted into new concepts. In turn, this movement is associated with the idea that There is no possible way to make an idea reach our mind without being connected to perceptions and which, therefore, must be able to be empirically verifiable. Otherwise it would be a fantasy.

This conception of where ideas came from led empiricists such as David Hume to reject philosophical positions about more metaphysical ideas, such as the existence of God, the soul or the self. This was motivated by the fact that these concepts and any other spiritual idea do not actually have a physical object from which they emanate, that is, there is no empirically experiential element from which the idea of God, the soul or the self is derived. .

2. Logical positivism

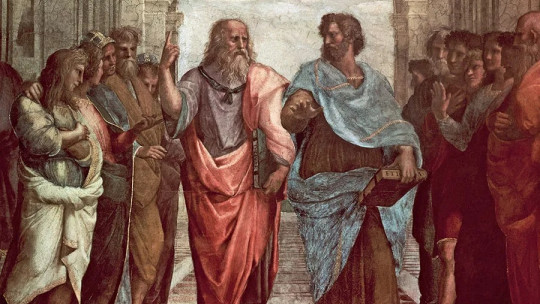

The philosophical current that has been most related to verificationism is, without a doubt, logical positivism Until the 1920s, the reflections made about science were characterized by being the result of isolated thinkers, philosophers who had little interaction with each other and who chose to debate other issues of philosophical interest, although this does not mean that There were no precedents in debate about how the scientific should be delimited.

In 1922, what was called the Vienna Circle was formed in Austria , a group of thinkers who met for the first time to discuss at length what science was, including both philosophers and scientists. The members of this circle cannot be considered “pure” philosophers, since they had worked in some particular scientific field and had gained an idea of what science was from their first-hand experience.

As a result of this group, the epistemological current of logical positivism emerged, having among its great references figures such as Rudolf Carnal (1891-1970) and Otto Neurath (1882-1945). This movement made verificationism its central thesis with the purpose of unify philosophy and science under a common naturalistic theory of knowledge His objective was that, if achieved, what was scientific could be clearly delimited from what was not, focusing research efforts on ideas that would really contribute to the development of humanity.

3. Pragmatism

Although pragmatism appeared before logical positivism, its influence on this second movement was rather scarce, although they did have in common their interest in verifying knowledge to consider it significant. Likewise, there are quite a few differences between both movements, the main one being the fact that pragmatism was not in favor of completely rejecting disciplines such as metaphysics, morals, religion and ethics for the simple fact that many of its postulates were not empirically demonstrable, something that the positivists were in favor of.

The pragmatists considered that, rather than rejecting metaphysics, ethics or religion for the simple fact of not surpassing the principle of verification, It was appropriate to propose a new norm to be able to carry out good metaphysics, religion and ethics without forgetting the fact that they are not empirically demonstrable disciplines but that does not make them less useful depending on the context.

4. Forgery

The opposite idea or, rather, antagonistic to verificationism is falsificationism This concept refers to the fact that an observational fact must be sought that can nullify an initial statement, hypothesis or theory and that, if not found, the original idea is reinforced. Verificationism would be the opposite in the sense that empirical evidence is sought to demonstrate the proposed theory, so that it is corroborated and, if not, it is considered that it has not passed the verification criterion. Both concepts are part of the problem of inductivism.

It is commonly believed that it was Karl Popper (1902-1994) who rejected the requirement that for a postulate to be significant it must be verifiable, asking that they be falsifiable instead. Anyway, Popper later indicated that his demand for falsifiability was not intended to be a theory of meaning, but rather a methodological proposal for the sciences But despite this fact, there are many who group Popper in the group of verificationists, despite him being a fair critic of verificationism.

This problem refers to the fact that something universal cannot be stated from the particular data that experience offers us. For example, no matter how many millions of white swans we see, we cannot affirm that “all swans are white.” On the other hand, if we find a black swan, even just one, we can affirm without a doubt that “Not all swans are white.” It is for this same idea that Popper chooses to introduce falsificationism as a criterion for scientific demarcation.