The life of medieval monasteries became world famous in 1980, when The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco’s magnificent best-seller, was published (1932-2016). In the novel, which masterfully mixed thriller with history and medieval philosophy, we witnessed the daily life of a 14th century Benedictine abbey, cruelly plagued by murders that seem meaningless.

In The Name of the Rose the rhythm of the days is interrupted by events, but the reality is that life in medieval monasteries followed a fairly strict scheme, around which the daily lives of the monks revolved. From the first mass in the middle of the night (Matins) to the last religious service (which took place around 6 in the afternoon), passing through work hours and meals; Everything was structured and scrupulously organized.

In today’s article we review how people lived in medieval monasteries, in addition to briefly reviewing the history of monasticism and its most important manifestations.

Life in a medieval monastery: from matins to compline

In the Middle Ages, especially before the rise of cities and, therefore, of the mechanical clock (13th century), the hours followed the rhythm of the liturgy of the monasteries The so-called canonical hours were those that guided not only the monks, but also the inhabitants of the small rural villages that were founded around the monasteries.

Towards the 9th century, and thanks to the impetus given to the order by the Carolingians, the Benedictine rule became the sole ruler of the monasteries of medieval Europe. This rule, created by Saint Benedict of Nursia (4th century), established a strict succession of daily moments that focused on the maxim of the order: ora et labora (pray and work).

But before stopping to take a closer look at daily life in a medieval monastery, let’s briefly review the history and origins of Western monasticism. The origin of the monastic current in the West must be sought, although it may seem paradoxical, in the eastern part of the Roman Empire By the 3rd century AD Christianity is widespread throughout the Roman world; It is then that ascetics and hermits begin to emerge in Egypt and Syria who retire to the desert or to remote places to dedicate themselves to meditation, prayer and fasting.

Asceticism became a true phenomenon at the European level, since there were many men and women who chose this type of existence, for them, much closer to Christ and the essence of Christian spirituality.

However, the places to which they retreated posed numerous dangers: from dangerous vermin to bandits, through illnesses and physical problems that required certain care and dedication, impossible to find in solitude. Thus, these first hermits began to meet in small groups; first, only for moments of prayer and religious celebration Later, however, these men and women ended up living together in monasteries, most of them practically uninhabitable (some were nothing more than caves), without respecting, of course, any type of separation between the sexes, something that happened much later.

In reality, the strict separation between monks and nuns did not come until the 11th century, with the Gregorian reform. Until then, it was very common to find dual monasteries, in which men and women lived together in common spaces without major problems. The mixed reality was reinforced by the religious needs of the nuns, who needed the spiritual assistance of their male colleagues, as well as the need for protection, since we remember that many of the monasteries were located in remote and inhospitable places.

Thus, little by little, a network of monasteries was formed throughout the medieval West, which It ended up emerging in the 10th century with the founding, in Burgundy, of the monastery of Cluny, the epicenter of a considerable monastic network that spread throughout Europe

The daily life of monks: ora et labora

We have already commented how, in the 8th century, the Benedictine rule was solidly established in Europe, to the point that the Germanic Council of 742 (and, more firmly, the abbey council of Aachen of 817), established the rule of Saint Benedict as the only one valid for Western monasticism. The Benedictine code is based on concepts such as obedience and humility, as well as the avoidance of leisure as a generator of all vice. Thus, the Benedictine maxim will be the famous ora et labora, the “pray and work” that would dictate the daily existence of medieval monks and nuns.

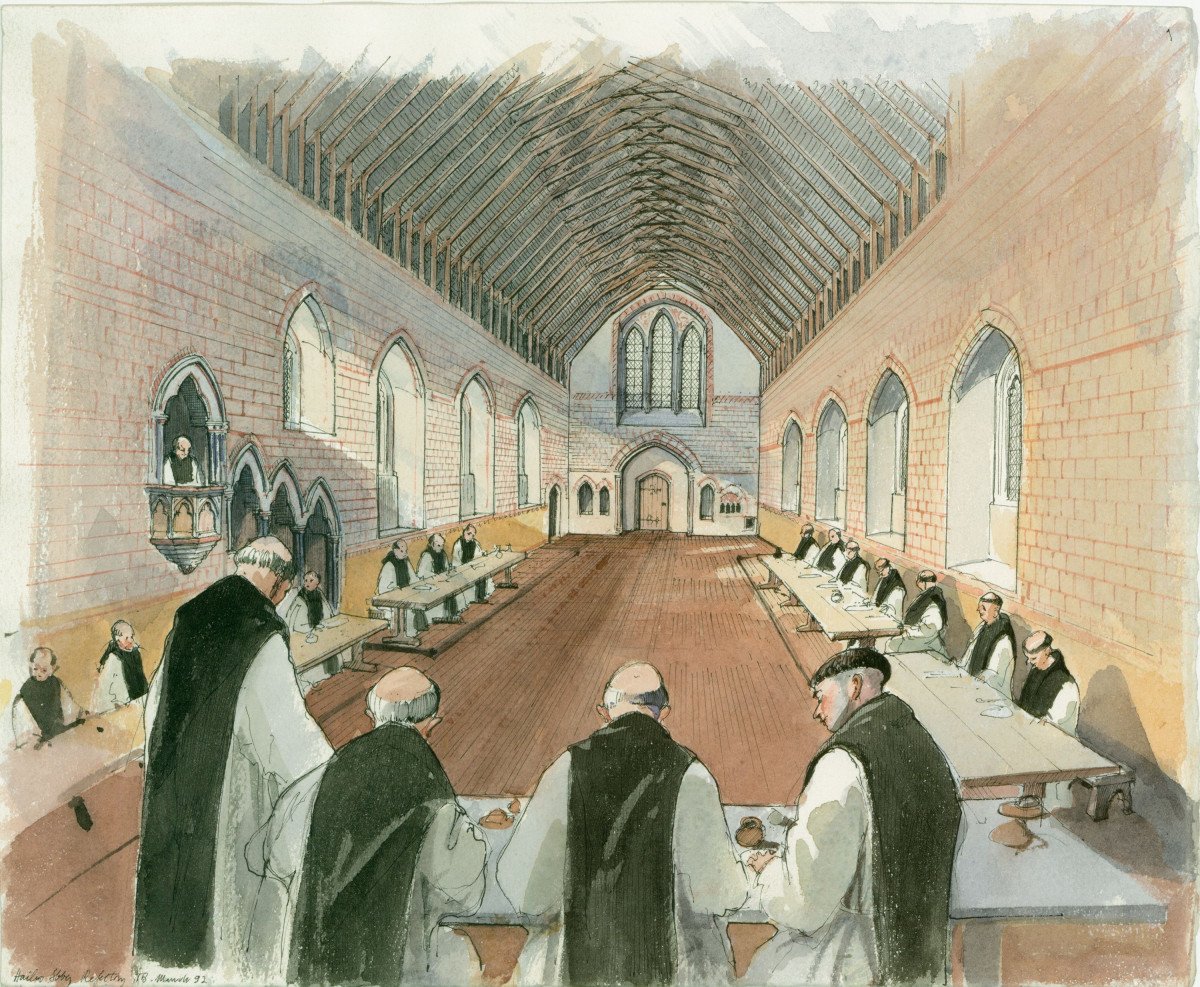

As we already briefly noted in another section, the monastic day was divided between work and prayer. The first liturgy took place before sunrise (matins), which was usually between 2 and 3 at night. Later, around 4:30 in the morning (or 6 in the summer), the monks went to the lauds, just at sunrise

A period of work followed, which the monks dedicated to their respective tasks. The morning mass interrupted the work again, as did the subsequent meeting, which took place in the chapter house, where the monks discussed various matters that concerned the monastery. Then, they returned to work until the midday liturgy, which was followed by lunch, which, in winter, was usually the only one of the day.

After lunch, work resumed, until 4:30 in the afternoon in winter and 6 in summer, when the second meal was eaten. After that, more work, until the lack of light made its execution difficult. Bedtime used to vary between 6 and 8 p.m., depending on the time of year

What do medieval monks do?

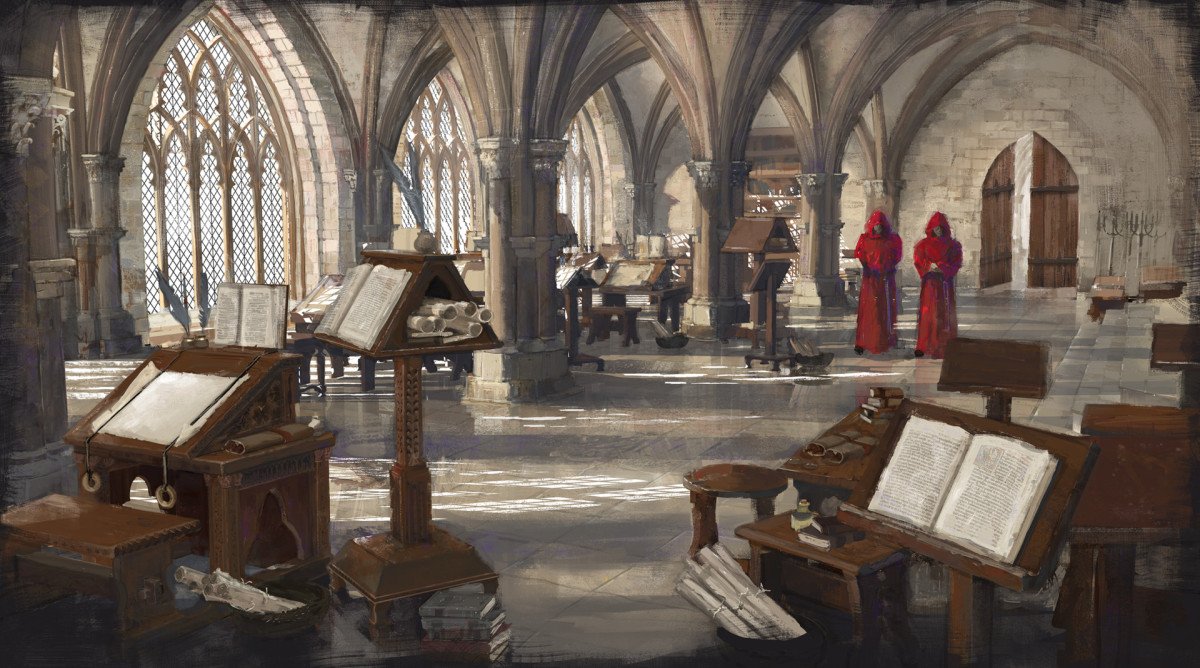

At this point, we could ask ourselves: what did the monks dedicate their working hours to? Well, the chores to which a member of the community could dedicate themselves were varied. From the most manual jobs (mainly dedicated to cleaning and caring for animals), common in small or poor monasteries that did not have lay people to carry out this type of tasks, to the most “noble” jobs, such as librarian, apothecary or, above all, that of copyist and illuminator of manuscripts

In the Middle Ages, the codex or book became an extremely expensive and difficult element to make. The support is no longer papyrus, but parchment, obtained from the skin of sheep. The preparation of the supports was long and meticulous, as well as the pigments that had to be used in the miniatures. By the way: the word miniature, with which we refer to the illuminations of medieval codices, does not refer to the size of the illustration, since many of them were full page. The word comes from minium, one of the materials used for this work.

Thus, the task of copyist and illuminator is one of the most widespread and respected among monks. Despite being manual work, this activity was not considered “vulgar”, since it belonged to the religious and, therefore, intellectual sphere. Thanks to medieval copyists, many works of antiquity were recovered and spread throughout Europe, which also remained safe in the libraries of monasteries

On the other hand, in the monasteries there were so-called monastic schools, intended for the education of future monks, but which usually also received the sons and daughters of the aristocracy. It was quite common for these children, especially if they were not the firstborn, to stay in the monastery and profess their vows, which was frankly not a bad prospect, considering that they had guaranteed access to knowledge and a good diet, because Although the consumption of meat was not common and was restricted to the sick and festivities, legumes, vegetables and fish were abundant, as well as abundant wine and beer. Another advantage was the isolation from pests and other diseases that decimated the population, since we must remember that the monasteries were self-sufficient units, and that they were often walled

From this we cannot deduce, however, that the monks and nuns never left the monastic grounds. Although the outings were not abundant and, furthermore, they needed the permission of the abbot or abbess, it was not unusual to find monks wandering the roads, from monastery to monastery, with some diplomatic mission in hand or, simply, specially sent. to acquire a special codex for copying and preservation in the monastery from which they came.

This is also true in the case of female communities. The myth of the medieval nun locked within four walls is just that, a myth. In fact, we have already commented how, before the 11th century, men and women lived together in the monasteries and shared common places. In addition to that, many nuns left their monasteries to visit relatives or carry out some diplomatic activity (like their male counterparts), sent, in this case, by the abbess

Abbots, priors and abbesses

The monastic community was responsible for choosing the abbot or abbess in a chapter session. The position was usually for life, so it was not unusual to find abbots or abbesses chosen at a very young age who held office until their death in old age. On the other hand, the prior usually helped the abbot and, in the cases of monasteries dependent on an abbey, he was the one who held the highest position (in this case, they were called priories).

The abbot or abbess acted de facto as a true feudal lord. The rest of the monks owed him obedience and respect, and were responsible for receiving the income from the lands with which the community was maintained In the case of the abbesses, their power did not diminish at all because they were women, and there were quite a few daughters of kings and high noble titles who ended up ruling over a community.

Lay people, novices and oblates

We cannot forget that in the monasteries there were not only monks and nuns, but also lay people, who carried out some of the daily tasks of the community. These lay people lived in their own houses, located on the monastery grounds, and could have their own family, since they were not bound by the vow of chastity.

The presence of lay people was also normal, of course, in the inn, the building where travelers and visitors were welcomed. On the other hand, in the case of female monasteries, it was not at all unusual for dominae or ladies to live or stay temporarily within the walls of the monastery high-ranking lay ladies who had acted as clients of the foundation and construction of the building.

Finally, we must mention the novices, young people over fifteen years of age who were not yet monks, and the oblates, children under ten years of age who lived with the community, studied in the monastic school and who, generally, ended up professing the vows once adults.