Psychology has given birth to a large number of theories and theoretical models through which it seeks to explain human behavior.

They are concrete proposals that in most cases They only seek to explain a small part of the set of topics that psychology can explain, since they are based on the work that many researchers have been carrying out months, years and decades ago. However, this whole network of proposals had to start at some point when practically nothing was known about how we behave and perceive things.

What was it like to face the study of Psychology in those years? What did it mean to have to lay the foundations of modern Psychology?

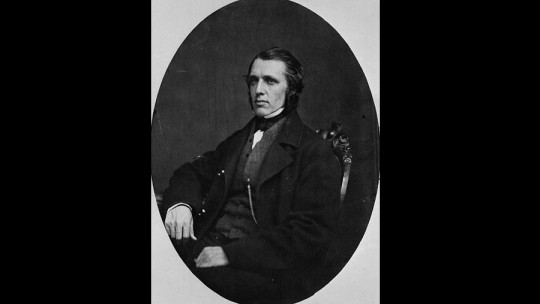

To answer these questions it is convenient to look back and review the life and work of William James a philosopher and psychologist who set out to investigate one of the most basic and universal concepts when it comes to the study of the mind: the consciousness.

Who was William James?

William James’s life began like that of any representative of the American upper classes. He was born in 1842 in New York, into a wealthy family, and the fact of having access to his parents’ considerable financial resources allowed him to study in good schools, both in the United States and in Europe, and soak up the different philosophical and artistic trends and currents that characterized each place he visited. His father was also a famous and well-connected theologian, and the bourgeois culture that surrounded the entire family probably helped William James to be ambitious when it came to setting life goals.

In short, William James had everything to become a well-positioned person: the material resources and also the influences of the New York elites related to his relatives accompanied him in this. However, although in 1864 he began studying medicine at Harvard, a series of academic hiatuses and health complications meant that he did not finish his studies until 1869 and, in any case, He never practiced as a doctor

There was another area of study that caught his attention: the binomial formed between Philosophy and Psychology, two disciplines that in the 19th century had not yet completely separated and that at that time studied matters related to the soul and thought.

Psychologist William James is born

In 1873, William James returned to Harvard to teach Psychology and Philosophy Certain things had changed since he graduated in medicine. He had subjected his life experience to a philosophical examination, and he had put so much effort into it that he saw himself strong enough to become a professor despite having received no formal education on the subject.

However, despite not having attended philosophy classes, the topics in which he became interested were of the type that had marked the beginnings of the history of the great thinkers. Since he could not base his studies on previous research in Psychology because this had not yet been consolidated, focused on studying consciousness and emotional states That is, two universal themes closely linked to philosophy and epistemology as they are present in all our ways of interacting with the environment.

Consciousness, according to James

When approaching the study of consciousness, William James encountered many difficulties. It couldn’t be any other way, since, as he himself recognized, It is very difficult to even define what consciousness is or to be aware of something And, if one does not know how to define the object of study, it is practically impossible to direct research on it and make it come to fruition. That is why James’s first great challenge was to explain what consciousness is in philosophical terms and then be able to test its operating mechanisms and verifiable foundations.

He managed to get closer to an intuitive (although not entirely exhaustive) idea of what consciousness is by drawing an analogy between it and a river. It is a metaphor to describe consciousness as if it were an incessant flow of thoughts, ideas, and mental images Once again, at this point the intimate connection between William James’ approach to Psychology and philosophical themes can be seen, since the figure of the river had already been used many millennia before by Heraclitus, one of the first great thinkers of the West. .

The precedent of Heraclitus

Heraclitus faced the task of defining the relationship between “being” and change that apparently form part of reality. All things seem to remain and show qualities that make them stable over time, but at the same time all things change Heraclitus maintained that “being” is an illusion and that the only thing that defines reality is constant change, just like a river that, although apparently it is a single thing that remains, is still a succession of parts of water that is never repeated again.

William James believed it was useful to define consciousness as if it were a river because in this way he established a dialectic between a stable element (consciousness itself, what one wants to define) and another that is constantly changing (the content of this consciousness). He thus emphasized the fact that Consciousness is composed of unique and unrepeatable units of experience, linked to the here and now and that led from one “section” of the flow of thoughts to another part of it.

The nature of consciousness

This implied recognizing that in consciousness there is little or nothing that is substantive, that is, that can be isolated and stored for study, since everything that passes through it is linked to the context The only thing that remains in this “current” is the labels that we want to put on it to define it, that is, our considerations about it, but not the thing itself. From this reflection William James reaches a clear conclusion: Consciousness is not an object, but a process, in the same way that the operation of an engine is not in itself something that exists separately from the machine

Why does consciousness exist, then, if it cannot even be located in a certain time and space? For our body to function, he said. To allow us to use images and thoughts to survive.

Defining the stream of thoughts

William James believed that in the flow of images and ideas that constitute consciousness there are transitive parts and noun parts. The former constantly refer to other elements of the stream of thoughts, while the latter are those in which we can stop for a while and notice a sensation of permanence. Of course all these parts of consciousness are transitory to a greater or lesser extent. And, more importantly, they are all private, in the sense that The rest of the people can only know them indirectly, through our own awareness of what we experience

The practical consequences of this for research in Psychology were clear. This idea meant admitting that experimental psychology was incapable of fully understanding, through its methods alone, how human thought works, although it can help. To examine the flow of thoughts, says William James, We must begin by studying the “I”, which appears from the stream of consciousness itself

This means that, from this point of view, studying the human psyche is equivalent to studying a construct as abstract as the “self.” This idea did not please experimental psychologists, who preferred to focus their efforts on studying verifiable facts in a laboratory.

The James-Lange Theory: Do we cry because we are sad or are we sad because we cry?

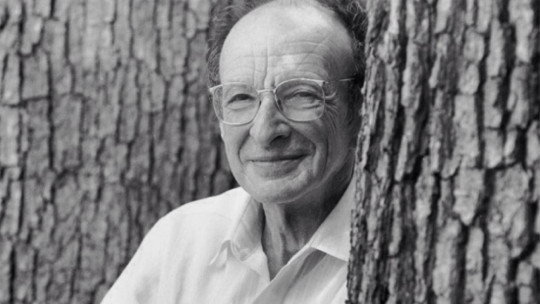

Once these basic considerations were made about what consciousness is and what it is not, William James was able to begin to propose concrete mechanisms by which our thought flows guide our behavior. One of these contributions is the James-Lange Theory, devised by him and Carl Lange almost at the same time, according to which emotions appear from the awareness of one’s own physiological states.

For example, We do not smile because we are happy, but we are happy because our consciousness has been informed that we are smiling In the same way, we do not run because something has scared us, but we feel scared because we realize that we are fleeing.

This is a theory that goes against the conventional way in which we conceive the functioning of our nervous system and our thoughts, and the same thing happened at the end of the 19th century. Today, however, We know that William James and Carl Lange are most likely only partially right , since we consider that the cycle between perception (seeing something that scares us) and action (running) is so fast and with so many neural interactions in both directions that we cannot speak of a causal chain in only one direction. We run because we are scared, and we are also scared because we run.

What do we owe William James?

William James’ beliefs may seem bizarre today, but the truth is that a large part of his ideas have been the principles on which interesting proposals have been built that are still valid today. in his book The Principles of Psychology (Principles of Psychology), for example There are many ideas and notions that are useful to understand how it works of the human brain, despite having been written at a time when the existence of the synaptic spaces that separate neurons from others was just being discovered.

Furthermore, the pragmatist approach he gave to Psychology is the philosophical foundation of many psychological theories and therapies that place more emphasis on the usefulness of thoughts and affective states than on their correspondence with an objective reality.

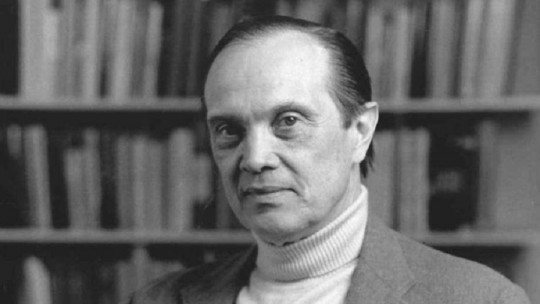

Perhaps because of this union between Psychology and the philosophical current of American pragmatism (which would later also define the behaviorist BF Skinner) and due to the fact that he was one of the pioneers in American lands, William James is considered the father of Psychology in the United States and, much to his regret, the person in charge of introduce to his continent the Experimental Psychology that was being developed in Europe by Wilhelm Wundt.

In short, although William James had to face the costly mission of helping to establish the beginnings of Psychology as an academic and practical field, it cannot be said that this task was ungrateful to him. He showed true interest in what he was researching and was able to use this discipline to deploy exceptionally sharp proposals about the human mind. So much so that, for those who came after him, there was no choice but to accept them as good or strive to refute them.