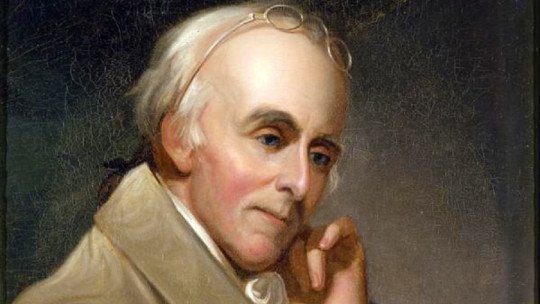

This is how he is known, “the father of American psychiatry”, for his innovative interest in the relationship that the mind had on the body. But Benjamin Rush not only stood out in this sense; He was the first chemistry professor in the United States, as well as an enthusiastic doctor, abolitionist, humanist and one of the signers of the Act of Independence of the United States of America. Almost nothing.

Walk us through this Benjamin Rush biography one of the most outstanding of the American 18th century.

Brief biography of Benjamin Rush, doctor and revolutionary

Benjamin Rush was born in a time too brilliant to remain on the sidelines. In the 18th century, the Enlightenment lit the fuses of all nations and forever changed the face of the world. The English colonies in America, that is, what would later become the United States, were not far behind in this regard.

In 1740, the Philadelphia Charitable Church and College had seen the light, which would later become Philadelphia University and which at that time was dedicated to the education of the children of the city’s working-class families. In the 1750s it ran out of funds and Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) himself would take charge of its maintenance. On the other hand, the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), founded in 1746, became one of the most famous and respectable institutions of the time.

Childhood and youth of Benjamin Rush

In this context of cultural ferment, Benjamin Rush was born on January 4, 1746, the fourth child of a family of Quaker descent. His father, John Rush, a farmer and weapons manufacturer, renounces the family’s Quaker roots and baptizes his daughter in the local Episcopal Church. The parent dies when Benjamin is a six-year-old child, so The education of the boy and his six siblings, as well as their maintenance and support, falls on the mother, Susanna Hall, a liberal-minded Quaker

Little Rush’s intellectual talent soon becomes evident, because at only fifteen years old he obtained the Bachelor’s degree, which he obtained thanks to his studies at the Nottingham Academy in Maryland. The institution is chaired by his uncle, the Reverend Samuel Finley, who will play a very important role in the adolescent’s education.

Medicine as a goal

In Maryland, Rush acquired a humanist education, based on Latin and Greek, philosophy and mathematics, as befitted an enlightened man of his time.

But, despite being brilliant in these fields, young Rush’s sights are set on other areas. Always very interested in medicine, he began to study medical science with John Redman , a famous physicist from Philadelphia who teaches him the first rudiments. After studying with him for five years, Rush left in 1766 for Edinburgh, whose university is known throughout Europe for the prestige of its medical studies. A brilliant student, Rush obtained his degree in 1768. He was twenty-two years old and had an extensive career ahead of him.

Social concerns

After finishing his studies in Edinburgh, Rush did a medical internship at the St. Thomas Hospital in London, where he studied anatomy with the prestigious William Hunter (1718-1783). It is there where he meets Benjamin Franklin, one of the “founding fathers”, who in those years was established in the English capital fighting with Parliament to repeal the hated “Stamp Act”. Despite being four decades apart, the older Benjamin is genuinely impressed by the younger Benjamin, to the point that he finances part of his trip to France, with the goal of improving his medical skills.

The stay in France is not very beneficial for Rush, who does not see anything in the French country that catches his attention. The year is 1769, and what the young graduate ignores is that, just twenty years later, one of the most important revolutions in history will begin.

That same year, in the summer, Rush settled permanently in Philadelphia. Absolutely impregnated by the humanist ideas that he received during his education, as well as the liberal ideas of his mother, he began to practice professional medicine as a “doctor of the poor”, which gives us a clue about his social ideals. . During that same year, Rush is appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, making him the first professor of this subject in the United States

The humanistic and enlightened education that Rush had received is not only evident in his efforts to provide the most disadvantaged with the necessary medical help, but also in his fight against slavery and alcoholism, although on this issue there are certain contradictions.

In reference to the latter, and despite the fact that, apparently, Rush was only in favor of limiting the consumption of the drink (and not of eradicating it), he has been called “Father of the Temperance movement”, the anti-alcohol current that began to travel through the religious communities of the time. On the other hand, His position on slavery is even more controversial Although he was a fervent abolitionist all his life and even collaborated in the creation of the first anti-slavery society in the United States, it is known that he purchased a slave, William Gruber, and kept him throughout his life.

Revolution and independence

Another thing that Benjamin Rush is famous for is being part of the group that signed the United States Independence Act (1776). Indeed, his political position always revolved around a vehement republicanism and the idea that all nations should achieve self-government, which made him openly oppose the monarchy and any other manifestation that, in his opinion, undermined this freedom, both individual as well as social.

In 1775, Benjamin meets Julia Stockton, the very young daughter of Richard Stockton, the lawyer who would also be, along with Franklin and others, one of the “founding fathers.” The couple married in 1776; Julia is sixteen years old and Rush just turned thirty. The following year, Benjamin accompanied his newly minted father-in-law and the Reverend John Witherspoon (who, by the way, had officiated at his wedding), both representatives of the state of New Jersey, to the Continental Congress of 1776, the second of the congresses that took place. carried out during the American War of Independence. In it, attendees endorsed the declaration of independence; Among the signatories was, as already mentioned, Benjamin Rush.

The father of American psychiatry

Benjamin Rush published his Medical Inquiries And Observations Upon The Diseases Of The Mind a year before his death, a work that for many experts represents the first publication on psychiatry in US history For Samuel Bernard Wortis, the author of the preface to the 1962 edition of the work (see bibliography), it was the country’s first comprehensible text on mental illness, and as such it exerted a very important influence on subsequent works.

During his work as a physician at the Pennsylvania Hospital (a position he held from 1783 until his death thirty years later) Rush carefully observed the behavior of the patients under his care, and carefully noted the psychological consequences of brain damage. and the consumption of drugs and alcohol (which, by the way, reaffirmed him in his fight against alcoholism). With his research, Rush was a pioneer in the study of the origin of mental illnesses and their treatment. The fame of his revolutionary discoveries meant that, in 1787 (and as he stated in a letter to a friend), he was assigned exclusively to the hospital’s “manic” patients.

One of the things that became clear to Benjamin after his work as a doctor in the hospital was that The mind was much more related to the body than the medicine of that time believed To this end, he promoted an appropriate diet for the sick, physical exercise and hydrotherapy treatment to relieve symptoms. Famous is the tranquilizing chair (something like a “calming chair”), a curious artifact designed by Rush in the 1810s that consisted of a robust chair that chained patients and had a wooden box on top to insert the head into. The idea was that mental illness was caused by an alteration in blood flow, and the chair position, sustained for long enough, was supposed to cause the necessary changes in arterial pressure for the symptoms of the illness to occur. they will be relieved.

Although today it may seem like a questionable practice to say the least, the truth is that Rush’s theories were very revolutionary in their time. Especially important for all later psychiatry was his conviction that the mentally ill should be treated appropriately, without forgetting their dignity And although this idea had been present for centuries (in medieval hospitals an active and healthy life was promoted for the mentally ill), it had fallen into certain disuse.

Innovative or obsolete?

Given this, it is difficult to imagine why some quarters considered Benjamin Rush’s practices somewhat obsolete. And, although he did a lot to advance the study of psychiatry, the truth is that his other medical methods are rather in question.

Rush was especially known in his time as a passionate advocate of bloodletting as an adequate solution to virtually all ills. In 1793, a violent episode of yellow fever broke out in Philadelphia, claiming many lives. With his characteristic vigor, Rush dedicated himself body and soul to helping the sick, to whom he applied purges with very high doses of mercury and the root of an American plant called jalapa, widely used by the ancient Aztecs. The idea was that the patient would have constant diarrhea, supposedly to “eradicate” the disease. Obviously, the only thing this strange method did was dehydrate the patient.

But what Rush earned the most detractors was for his almost obsessive practice of bleeding patients. Bleeding, that is, the removal of blood through an incision in the body, was a common practice in European medicine since ancient times. However, it seems that Rush took the practice to the extreme, to the point that they say he indoctrinated his students to stick almost exclusively to this method. In 1799, Rush was put on trial for the death of a patient whom he had bled. The doctor was acquitted, but his fame as the “prince of bloodletting” had already gone down in history, almost with the same magnitude as that of the “father of American psychiatry.”