At the beginning of the 20th century, many anthropologists who studied non-Western cultures could not avoid doing so with a deep ethnocentric bias nor avoid seeing them as less advanced and more savage simply because they were not like European-based cultures.

To make matters worse, Darwin’s findings were interpreted and applied to societies in a quite racist way by Galton and his followers, believing that the development of cultures followed a pattern similar to the biological one, and that all human groups followed a series of steps to get from barbarism to civilization.

However this changed with the appearance of Franz Boas and historical particularism , anthropological school that takes special consideration to the history of each culture and understands that they are not comparable. Let’s look a little more in depth at what supported this school of thought.

What is historical particularism?

Historical particularism is a current of anthropology that mainly criticizes linear evolutionary theories extended throughout the 19th century These theories were based on evolutionism applied to the anthropological field, specifically social Darwinism, which was based on evolution by adaptation and survival-improvement; and Marxism, which defended social evolution explained by class struggle.

Historical particularism maintains that it is necessary to analyze the characteristics of each social group from the group itself, not with external visions that induce all types of investigative biases. Besides, emphasizes the cultural-historical reconstruction of such a group in order to better understand it and understand how and why it has arrived at the cultural complexity it expresses.

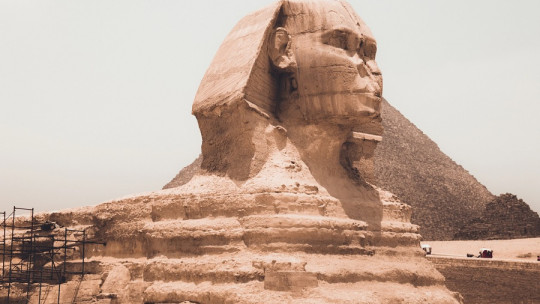

It is considered that this current was founded by Franz Boas, an American anthropologist of German Jewish origin who rejected several of the ideas coming from evolutionary theses on culture. He argued that each society was a collective representation of its historical past and that each human group and culture were the product of unique historical processes not replicable or comparable to those that would have occurred in other groups.

origins

At the beginning of the 20th century, several anthropologists began to review the evolutionary schemes and doctrines defended by both social Darwinists and Marxist communists. Both schools of thought had tried to explain how cultures are produced, but they had done so in a way that was too linear, ignoring that human diversity is too extensive to expect two human groups to experience the same thing and behave identically.

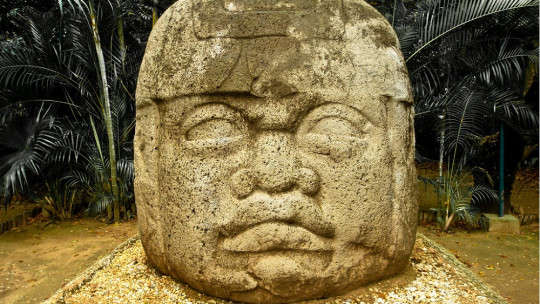

Franz Boas rejected unilinear evolutionism, that is, the idea that all societies have to follow the same path out of necessity and that reaches a specific level of development in the same way that the others have been able to do. Historical particularism was contrary to this idea, showing that different societies can reach the same degree of development through different paths.

According to Boas, the attempts that had been carried out during the 19th century to discover laws of cultural evolution and to schematize the stages of cultural progress were based on rather scant empirical evidence.

Ideas and main achievements of this current

Boas’s historical particularism maintained that aspects such as diffusion, similar environments, trade, and experiences of the same historical events can create similar cultural traits, but this does not mean that the same result has to occur in terms of complexity. According to Boas, there would be three features that can be used to explain cultural traditions : environmental conditions, psychological factors and historical connections, this last feature being the most important and the one that gives its name to this school of thought.

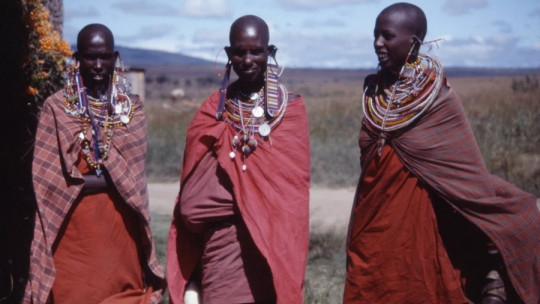

Another of the ideas defended by historical particularism, being one of the main ones, is that of cultural relativism. They are against the idea that there are higher or lower forms of culture, and that terms like “barbarism” and “civilization” demonstrate ethnocentrism, even of those anthropologists who claimed to be objective. People cannot help but think that our culture is the most normal, sophisticated and superior, while other cultural expressions are seen as deficient, primitive and inferior the more different they are from our human reference group.

Boas shows a relativistic vision in his work “Mind of Primitive Man” (1909) in which he explicitly says that there are no higher or lower forms of culture, since each culture has a value in itself and it is not possible to make a minimum comparison between them. Boas affirms that we should not compare different cultures from an ethnographic point of view, since in this way other cultures are being qualified based on our own culture and he believed that this was the methodology used by many social evolutionists.

To counteract the ethnocentric theories of many social evolutionists, Boas and his followers stressed the importance of carrying out field work when wanting to learn about non-Western cultures, getting to know these people firsthand. Thanks to this vision, many ethnographic reports and monographs began to emerge at the beginning of the 20th century, produced by the followers of this school and which came to demonstrate that Social evolutionists had ignored many of the complexities of the peoples they themselves had labeled “primitive.”

Another of the most important achievements of Boas and his school was to demonstrate that race, language and culture are independent aspects. It was observed that there were people of the same race who presented similar cultures and languages, but there were also those who did not speak the same language or have the same cultural traits, only sharing racial aspects. This weakened the social Darwinist notion that biological and cultural evolution went hand in hand and formed a simple process.

Franz Boas had interests in geography, specifically in the relationship between the geographical and the psychophysical, which is why he decided to travel and carry out his field work with Eskimos on Baffin Island, in the Canadian Arctic. While there he acquired the conviction contrary to ecological determinism, so shared by German geographers. He believed that history, language and civilization were independent of the natural environment , and that are very partially influenced by it. That is, the relationship between societies and their environment is not direct, and is mediated by their history, language and culture.

Criticisms of historical particularism

Boas’s historical particularism has had an important influence on other anthropologists and great thinkers of the 20th century. Among them we can find Edward Sapir, Dell Hymes and William Labov, who would found sociolinguistics and ethnolinguistics based on Boas’s field work and his visions on the relationship between language and territory, showing their own points of view. he. He also influenced other great figures of anthropology, such as Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead and Ralph Linton. But despite all this he was not immune to some criticism.

Among the most critical of historical particularism we have Marvin Harris, an American anthropologist who had great influence on cultural materialism. Harris considered that this current and, especially, the method that Boas himself used, focused too much on the point of view of the native this is its unconscious structure that the inhabitant himself would not know how to describe in empirical or objective terms (Emic) and did not give due importance to the scientific point of view and avoided comparisons in his research (Etic).

That is to say, for Harris, historical particularism had acquired a point of view that was too subjective, ethnocentric but with the culture itself being studied. Thus, he considered that this resulted in Boas’s works showing a profound absence of analysis. He also accused Boas of being obsessed with fieldwork, since, as we have mentioned, he believed that it was the basis of all ethnographic work, to the point where it was the only tool used to collect data.

Marvin Harris also believed that Boas made excessive use of the inductive method , obtaining general conclusions about cultures from particular premises. Harris himself believed that in science the use of the deductive method was fundamental and essential and that this would avoid the analysis of premises or individual factors, which in many cases were not so important as to be included in the anthropological work once the research had been completed. exploration.