The motto of Stanford prison experiment devised by psychologist Philip Zimbardo It could be the following: Do you consider yourself a good person? It’s a simple question, but answering it requires a little thought. If you think you are a human being like many other people, you probably also think that you are not known for breaking rules twenty-four hours a day.

With our virtues and with our defects, most of us seem to maintain a certain ethical balance when coming into contact with the rest of humanity. Partly thanks to this compliance with the rules of coexistence, we have managed to create relatively stable environments in which we can all coexist relatively well.

Philip Zimbardo, the psychologist who challenged human kindness

Perhaps because our civilization offers a framework of stability, it is also easy to read the ethical behavior of others as if it were something very predictable: when we refer to people’s morality, it is difficult not to be very categorical. We believe in the existence of good people and bad people, and those that are neither very good nor very bad (here probably between the image we have of ourselves) are defined by automatically tending towards moderation, the point at which neither one is very harmed nor the rest are seriously harmed. Labeling ourselves and others is comfortable, easy to understand, and also allows us to differentiate ourselves from the rest.

However, today we know that context plays an important role when it comes to morally orienting our behavior towards others: to prove it we only have to break the shell of “normality” on which we have built our practices and customs. One of the clearest examples of this principle is found in this famous investigation, conducted by Philip Zimbardo in 1971 in the basement of his faculty. What happened there is known as the Stanford prison experiment, a controversial study whose fame is partially based on the disastrous results it had for all its participants.

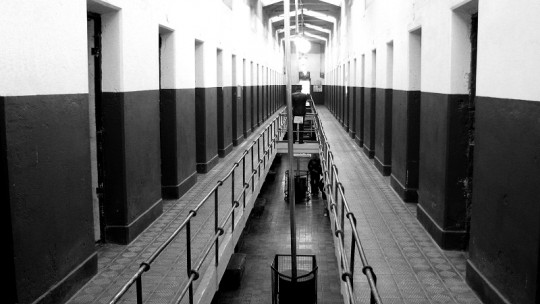

Stanford prison

Philip Zimbardo designed an experiment to see how people who had no contact with the prison environment adapted to a vulnerable situation in front of others. To do this, 24 healthy, middle-class young men were recruited as participants in exchange for payment.

The experience would take place in one of the basements of Stanford University, which had been converted to resemble a prison. The volunteers were assigned to two groups by lottery: the guards, who would hold power, and the prisoners, who would have to remain confined in the basement for the duration of the experimentation period, that is, for several days. As we wanted to simulate a prison in the most realistic way possible, the inmates went through something similar to a process of arrest, identification and imprisonment, and the clothing of all the volunteers included elements of anonymity: uniforms and dark glasses in the case of the guards. , and prisoner suits with embroidered numbers for the rest of the participants.

In this way an element of depersonalization in the experiment: the volunteers were not specific people with a unique identity, but formally became simple jailers or prisoners.

The subjective

From a rational point of view, of course, all these aesthetic measures did not matter. It remained strictly true that there were no relevant differences in height and build between guards and inmates, and they were all equally subject to the legal framework. Besides, the guards were forbidden to do harm to the inmates and their role was reduced to controlling their behavior, making them feel uncomfortable, deprived of their privacy and subject to the erratic behavior of their guards. In short, everything was based on the subjective, that which is difficult to describe in words but that equally affects our behavior and our decision-making.

Would these changes be enough to significantly modify the moral behavior of the participants?

First day in jail: apparent calm

At the end of the first day, there was nothing to suggest that anything remarkable was going to happen. Both inmates and guards felt displaced from the role they were supposed to fulfill, in some way. they rejected the roles that had been assigned to them. However, soon complications began. By the second day, the guards had already begun to see the lines blurring. separated his own identity and role that they had to comply with.

The prisoners, as disadvantaged people, took a little longer to accept their role, and on the second day a rebellion broke out: they placed their beds against the door to prevent the guards from entering to remove their mattresses. These, as forces of repression, used the gas from the fire extinguishers to end this small revolution. From that moment on, all volunteers in the experiment They stopped being simple students to become something else

Second day: the guards become violent

What happened during the second day triggered all kinds of sadistic behavior on the part of the guards. The outbreak of the rebellion was the first sign that The relationship between guards and inmates had become totally asymmetrical: the guards knew they had the power to dominate the rest and acted accordingly, and the inmates responded to their captors, implicitly recognizing their situation of inferiority, just as a prisoner would do who knows he is locked within four walls. A dynamic of dominance and submission was thus generated based solely on the fiction of “Stanford prison.”

Objectively, in the experiment there was only one room, a series of volunteers and a team of observers and none of the people involved were in a more disadvantaged situation than the others before the real judiciary and before the police trained and equipped to be so. However, the imaginary prison made its way little by little until it sprang into the world of reality.

Indignities become daily bread

At a certain point, the humiliations suffered by the inmates became totally real, as was also real the feeling of superiority of the false guards and the role of jailer adopted by Philip Zimbardo, who had to get rid of the disguise of investigator and make the office assigned to him his bedroom. , to be close to the source of problems that he had to manage. Certain inmates were denied food, forced to remain naked or make fools of themselves, and not allowed to sleep well. In the same way, Pushing, tripping and shaking were frequent

Stanford Prison Fiction It gained so much power that, for many days, neither the volunteers nor the researchers were able to recognize that the experiment should stop. Everyone assumed that what was happening was, in some way, natural. By the sixth day, the situation was so out of control that a noticeably shaken investigation team had to bring it to an abrupt end.

Consequences of role playing

The psychological mark left by this experience is very important. It was a traumatic experience for a large part of the volunteers, and many of them still find it difficult to explain their behavior during those days: it is difficult to make compatible the image of the guard or the inmate who left during the Stanford prison experiment and a positive self-image.

For Philip Zimbardo it was also an emotional challenge. He bystander effect For many days, it made external observers accept what was happening around them and, in some way, consent to it. The transformation into torturers and criminals by a group of “normal” young people had occurred so naturally that no one had noticed the moral aspect of the situation, despite the fact that the problems presented themselves practically suddenly.

The information regarding this case was also a shock to American society. First, because this kind of simulacrum alluded directly to the architecture of the penal system, one of the foundations of life in society in that country. But even more important is what this experiment tells us about human nature. While it lasted, Stanford prison was a place where any representative of the Western middle class could enter and become corrupt. Some superficial changes in the framework of relationships and certain doses of depersonalization and anonymity were capable of overthrowing the model of coexistence that permeates all areas of our lives as civilized beings.

From the rubble of what had previously been etiquette and custom, there arose not human beings capable of generating by themselves an equally valid and healthy framework of relationships, but rather people who interpreted strange and ambiguous norms in a sadistic way.

He reasonable automaton seen by Philip Zimbardo

It is comforting to think that lying, cruelty and theft exist only in “bad people”, people we label in this way to create a moral distinction between them and the rest of humanity. However, this belief has its weaknesses. No one is unfamiliar with stories about honest people who end up becoming corrupt shortly after reaching a position of power. There are also many characterizations of “antiheroes” in series, books and movies, people with ambiguous morality who, precisely because of their complexity, are realistic and, why not say it, more interesting and closer to us: compare Walter White with Gandalf the White.

Furthermore, when faced with examples of bad practice or corruption, it is common to hear opinions like “you would have done the same thing if you were in their place.” The latter is an unsubstantiated statement, but it reflects an interesting aspect of moral norms: Its application depends on the context Evil is not something attributable exclusively to a series of mean-spirited people, but is largely explained by the context we perceive. Every person has the potential to be an angel or a demon.

“The dream of the reason produces monsters”

The painter Francisco de Goya said that the dream of reason produces monsters. However, during the Stanford experiment, monsters emerged through the application of reasonable measures: the execution of an experiment using a series of volunteers.

Furthermore, the volunteers adhered so well to the instructions given that Many of them still regret their participation in the study today The great defect of Philip Zimbardo’s investigation was not due to technical errors, since all the measures of depersonalization and staging of a prison proved effective and everyone seemed to follow the rules at first. His fault was that It started from the overvaluation of human reason when deciding autonomously what is correct and what is not in any context.

From this simple exploratory test, Zimbardo inadvertently showed that our relationship with morality includes certain uncertainty quotas, and this is not something that we are always able to manage well. It is our most subjective and emotional side that falls into the traps of depersonalization and sadism, but it is also the only way to detect these traps and connect emotionally with others. As social and empathetic beings, we must go beyond reason when deciding what rules are applicable to each situation and how they should be interpreted.

Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford prison experiment teaches us that it is when we give up the possibility of questioning commands that we become dictators or willing slaves.