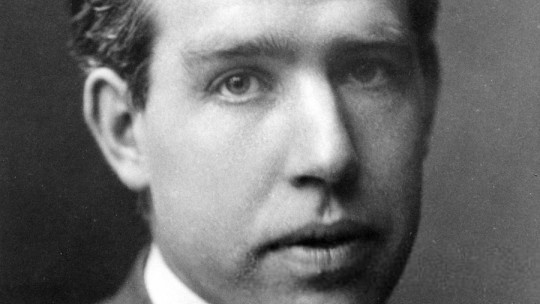

Werner Heisenberg is one of the most important figures in 20th century physics. His Uncertainty Principle along with his discoveries in quantum and nuclear theory have shaped this science throughout the last century and the present.

Born at the beginning of the 20th century, his life was marked by a notable rise thanks to his theoretical assumptions but, also, to the misfortune of having lived in a Germany that would soon be taken over by the Nazis who would have dark plans for their experiments.

Heisenberg’s life could have been that of someone who had built one of the deadliest weapons in history but, fortunately, this scientist had morals that prevented him from materializing it. Let’s see his story through this biography of Werner Heisenberg

Brief biography of Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg was born on December 5, 1901 in Würzburg, Germany Son of Annie and August Heisenberg, a humanities professor specializing in the history of Byzantium.

From a young age, Heisenberg was inclined towards mathematics, and to a lesser extent towards physics.

Academic career

In 1920 he tried to start his doctorate in pure mathematics with Ferdinand von Lindemann as a tutor, but he rejected him as a student because the professor was about to retire. Lindemann himself recommended that he do his doctoral studies with the physicist Arnold Sommerfeld as his supervisor, who accepted it willingly.

While doing his doctoral thesis, Heisenberg’s partner was Wolfgang Pauli, with whom he would collaborate closely in the development of quantum mechanics

During his first year he took mainly mathematics courses with the intention of working on number theory as soon as he had the opportunity, but as time went by, he began to become interested in theoretical physics. Werner Heisenberg tries to work on Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and his colleague Pauli advises him to dedicate himself to Atomic Theory in which there were still many discrepancies between theory and experimental evidence.

During his studies at the University of Munich he opted for physics, without giving up his interest in pure mathematics At that time physics was essentially an experimental science. Arnold Sommerfeld recognized his extraordinary abilities in mathematical physics, but also showed some opposition to Heisenberg’s doctoral degree due to his great lack of skill and inexperience in experimental physics. However, in the end Werner Heisenberg ended up earning a doctorate in 1923, presenting a work on fluid turbulence.

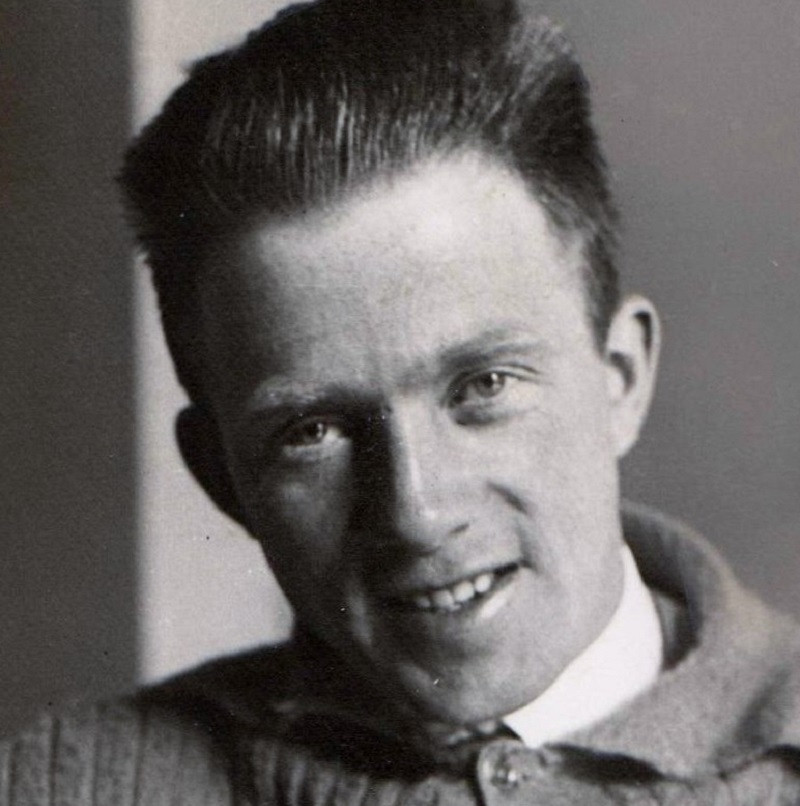

From Munich, Heisenberg went to the University of Göttingen, where Max Born taught and, In 1924, he moved to the Institute of Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen directed by Niels Bohr There Heisenberg would meet other important physicists such as Albert Einstein, and thus begin his most productive period, resulting in the creation of matrix mechanics. This achievement would be recognized by winning the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1932.

In 1927 he became a professor at the University of Leipzig, teaching theoretical physics.

Matrix mechanics and uncertainty principle

In 1925, Werner Heisenberg developed matrix quantum mechanics. This theory stands out for its great pragmatism because, instead of concentrating on the evolution of physical systems from beginning to end, it concentrates its efforts on obtaining information knowing the initial and final state of the system, without worrying about knowing precisely what happened in it. the middle.

Heisenberg proposes the idea of grouping information in the form of double entry tables , something that Max Born drew attention to, since it had already been studied by mathematicians, which was not different from matrix theory. Likewise, one of the most striking results is that matrix multiplication was not commutative, so the associations of physical quantities with matrices would have to reflect that mathematical fact. As a consequence of this, Heisenberg states the Indeterminacy Principle.

The so-called uncertainty or indeterminacy principle, also called Heisenberg’s Principle, states that it is not possible to know, with arbitrary precision and when the mass is constant, the position and momentum of a particle. From this it follows that the product of the uncertainties of both magnitudes must always be greater than that of Planck’s constant.

The statement of the Uncertainty Principle caused a lot of stir among physicists of the time since it meant the definitive disappearance of classical certainty in physics and the introduction of an indeterminism that affected the foundations of matter and the material universe. This principle supposes the practical impossibility of carrying out perfect measurements since, the simple presence of The observer disturbs the values of the other particles being considered and influences the measurement being carried out.

Werner Heisenberg also predicted, thanks to the principles of quantum mechanics, the dual spectrum of the hydrogen atom and also managed to explain that of the helium atom. His work on nuclear theory also allowed him to predict that the hydrogen molecule could exist in two states one as orthohydrogen, in which the nuclei of its two atoms rotate in the same direction, and another as parahydrogen, in which its nuclei rotate in opposite directions.

Second World War

In 1935 he attempted to replace Sommerfeld upon his retirement as a professor in Munich. However, with the rise of the Nazis, Heisenberg’s wishes were cut short.

The Nazi Party wanted to eliminate all “Judaizing” physical theories , and quantum mechanics and relativity fell into that curious category, both theories taught by Heisenberg in his classes and whose references were the Jews Max Born and Albert Einsen. As a consequence, the Nazis prevent Heisenberg’s appointment.

However, his destiny would change when, in 1938, the Nazis “kindly” invited him to direct their attempt to manufacture an atomic weapon. For this reason, between 1942 and 1945, Werner Heisenberg managed to direct the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin. During World War II he worked with Otto Hahn, one of the discoverers of nuclear fission, collaborating in the manufacture of a nuclear reactor.

For many years there was doubt about whether this project failed because its members simply did not succeed or because Heisenberg and his collaborators expressly sabotaged it by suspecting what Adolf Hitler could have done with an atomic bomb.

In September 1941 Heisenberg went to Denmark to visit Niels Bohr. In an act that according to the Nazis could only have been classified as treason and that put him seriously in danger, Heisenberg spoke to Bohr about the German atomic bomb project and even made him a drawing of a reactor

Heisenberg knew that Bohr had contacts outside unoccupied Europe and proposed a joint effort to have both Axis and Allied scientists delay nuclear research until the war was over. In June 1942, another German scientist, J. Hans D. Jensen, told Bohr that German scientists were not working on a nuclear bomb, but only on a reactor.

Heisenberg and other German scientists always claimed that, for moral reasons, they did not attempt to build the Nazi atomic bomb , in addition to the fact that the circumstances were not right to do so. These statements were denounced by scientists who participated in the Manhattan Project, stating that Heisenberg had not really manufactured the German atomic bomb because he erred in his calculations of the necessary amount of Uranium-235 and the critical mass to sustain the reaction.

Heisenberg on new nuclear technology

At the end of the war in Europe and as part of Operation Epsilon, Heisenberg along with other scientists, including Otto Hahn, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Max von Laue, was arrested and interned in a country house called Farm Hall in England. This prison house had hidden microphones that recorded all the prisoners’ conversations.

While in that house, on August 6, at six in the afternoon, Heisenberg and his fellow inmates listened to a BBC report on the Hiroshima atomic bomb The following evening, Werner Heisenberg gave a talk to his colleagues as a report, which included a roughly correct estimate of the critical mass and Uranium-235 needed, as well as the design features of the bomb.

This speech is considered proof that Heisenberg really could have made these calculations when he worked for Nazi Germany, but did not want to, which gives strength to the argument that he did not really build the bomb due to moral objections.

Perhaps his phrase that best summarizes his position on the final use that ended up being given to atomic theory is the following:

“Ideas are not responsible for what men make of them.”

Last years

After the final end of the war, Heisenberg was eventually released and allowed to continue working in physics in his native Germany. In 1946 he was appointed director of the Max Planck Institute, and later organized and directed the Göttingen Institute of Physics and Astrophysics which was moved to Munich in 1958.

In that city Heisenberg concentrated on research on the theory of elementary particles, the structure of the atomic nucleus, the hydrodynamics of turbulence, cosmic rays and ferromagnetism.

In 1970 he was awarded the Sigmund Freud Prize for Academic Prose. He would die a few years later, on February 1, 1976 in Munich, at the age of 74.