Psychology experienced important development throughout the 20th century due to the proliferation of great researchers.

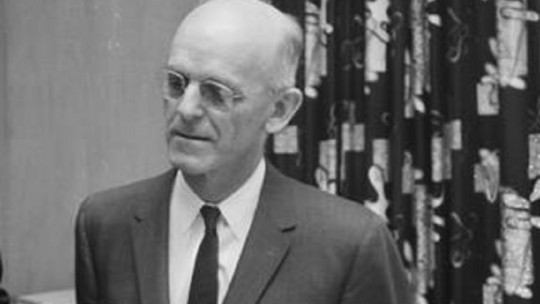

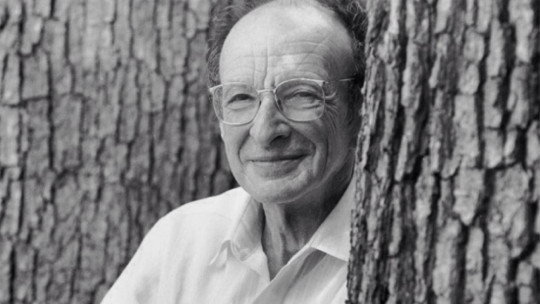

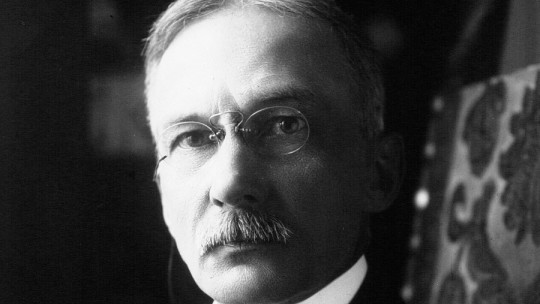

One of these authors was Orval Hobart Mowrer, whose life we will be able to know thanks to this article We will go through the most notable episodes of his life while discovering the most interesting contributions that this psychologist made during his career.

Brief biography of Orval Hobart Mowrer

Orval Hobart Mowrer was born in the city of Unionville, Missouri, United States, in 1907 He was raised on the family farm, although they later moved to a more urban area so Orval could attend school and receive the education he needed.

His father died when he was only 13 years old, which marked his development and practically his life in general. This event was the trigger for Orval Hobart Mowrer to develop a deep depression, a pathology that, in a more or less intense way, was going to accompany him until the end of his days.

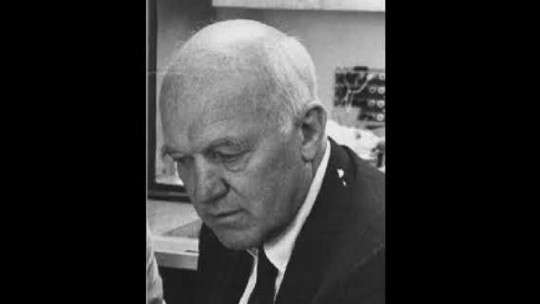

Despite how difficult his school years were, he managed to overcome his studies and enter the University of Missouri, where he enrolled in 1925 to train as a psychologist , since the understanding of the human mind was what really interested him. While studying this degree, he began to practice at that same institution, collaborating in the laboratory of Max Friedrich Meyer.

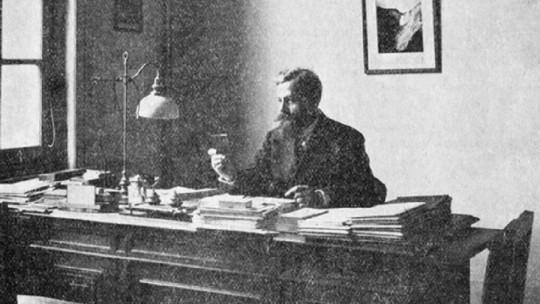

Meyer was a German, with a doctorate in physics, who had trained as a behavioral psychologist, and had emigrated to America at the end of the 19th century. This author was a great influence on Orval Hobart Mowrer, who adopted the framework of behaviorism for his research

Throughout these years, Mowrer carried out a study, as work for a sociology course. This study involved distributing a questionnaire to students in which they had to answer questions about sexual behaviors and possible causes for the deterioration of the institution of marriage in the United States. At a time when these questions could not be discussed so openly, the study turned out to be too daring.

Due, The university expelled two professors who were involved (including Meyer himself), and prevented Orval Hobart Mowrer from finishing his studies at that institution This fact caused the American Association of University Professors to harshly criticize the decision made by the University of Missouri.

Completion of studies and beginning of professional career

Orval Hobart Mowrer was forced to move elsewhere in order to complete his training. Therefore, he enrolled at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore, Maryland. At this institution he would complete his studies as a psychologist, learning, among others, from authors such as Knight Dunlap. Furthermore, his stay in this institution allowed him to meet Molly, a classmate who would eventually become his wife and mother of his three children.

The next step was to obtain a doctorate, a distinction he achieved thanks to research on spatial orientation in pigeons Throughout these years he once again suffered from episodes of depression, which reappeared in his life. To try to alleviate this illness, she underwent therapeutic treatment based on psychoanalysis.

Already in 1932, Orval Hobart Mowrer became a doctor of psychology. From then on, he began a pilgrimage to different American universities to carry out postdoctoral work. He started at Northwestern and Princeton, until he got a scholarship to Yale University.

There he investigated learning processes, conducting conditioning experiments with electric shocks and anticipatory lights. He discovered, among other things, that the response to the conditioned stimulus of light was more powerful than to the discharge itself Also, after the electric shock, the physiological conditions of the subjects experienced great relaxation.

This is how Orval Hobart Mowrer discovered the anticipatory function of anxiety , since it acted as a form of preparation for an aversive stimulus that was imminently arriving. He continued studying these phenomena at Yale, until in 1940 he was offered a position to practice at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

At this prestigious institution he met Henry Alexander Murray and another series of important researchers, with whom he founded Harvard’s department of social relations. At this time he suffered another of his depressive episodes, which he again tried to alleviate through psychoanalysis, directed by Hans Sachs, although he had less and less confidence in this methodology.

After the outbreak of World War II, Orval Hobart Mowrer collaborated with his country, joining the Office of Strategic Services. His job was to design tests that would serve to train intelligence agents. Therefore, the objective of these tools had to be to generate stress high enough so that only those who were trained for this type of work could overcome it.

Throughout his stay in this office, He was also able to learn from psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Harry Stack Sullivan which pointed out the importance of certain dysfunctions in relationships between people, such as lack of honesty, in generating certain psychopathologies, an idea that Mowrer would not forget.

Stage at the University of Illinois

After the end of the war, Orval Hobart Mowrer returned to his work at Harvard, but a few years later, in 1948, he moved with his family to Illinois, as the university in this city offered him a position as a researcher. Here He continued to develop the model for which he was already recognized, which was the two-factor theory

These two factors or dimensions would refer to the two forms of conditioning that would be involved in the processes that give rise to a fear or a phobia. Classical conditioning, on the one hand, would convert a neutral stimulus (a spider, a plane, a dog or any other element) into a conditioned and henceforth aversive stimulus.

On the other hand, instrumental conditioning would cause any element that resembles that of the original situation in which that fear was established to cause the same conditioned response, in this case anxiety. This is one of the models used by behaviorism, which is still valid today, despite the fact that Orval Hobart Mowrer worked on it for the first time in 1939.

But it was not the only topic this author focused on during his work as a researcher for the University of Illinois. Likewise, he worked in clinical psychology. Definitively leaving psychoanalysis behind, he returned to the ideas he had learned from Harry Stack Sullivan and studied the effect of interpersonal relationships based on honesty and integrity as a means to overcome psychopathologies

So much so, that he proved it firsthand, coming clean to his own wife about some dishonest behaviors that he himself had committed. After this catharsis, he lived almost a decade free of depressive symptoms, but unfortunately they had not disappeared forever.

In fact, in 1953, when he was already an eminence in his field and was about to accept the position of president of the APA (American Psychological Association), He experienced the biggest relapse he had ever had in his entire life , to the point that he had to be admitted to the hospital, where he would remain for more than three months. His depression was compounded by psychotic episodes.

Integrity groups and later years

In the years to come, Orval Hobart Mowrer He continued to perfect his system of integrity therapy, working with his own students and later with groups of people who had abused alcohol or drugs In these integrity groups, cathartic work was carried out in which any behavior was allowed, except physical aggression.

Some of the principles used in this type of work are maintained today for certain rehabilitation therapies against substance abuse, so Mowrer was a pioneer in that sense. In any case, the work with the groups ended in the 70s.

Another of Orval Hobart Mowrer’s statements is that there was an important genetic basis for psychopathology which was paradoxical, since he had dedicated many years of his career to studying dishonest behavior as a catalyst for psychological illnesses.

Although he suffered from the effects of depression throughout his life, he had the perspective that experiencing this illness had helped him carry out much of his research throughout his career.

His last years of life were marked by a delicate state of health Added to this was the death of his wife in 1979. Only three years later, in 1982, he decided to take his own life. He was 75 years old.