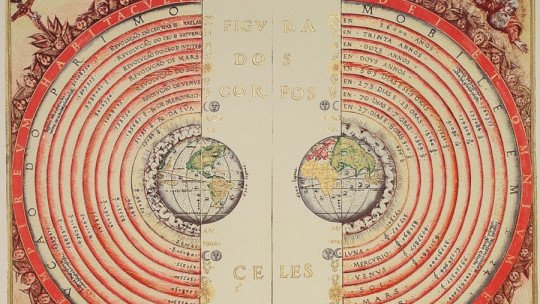

It is more than likely that you have heard of it. The geocentric theory comes from the Greek words geo (“earth”) and kentron (“sting”, reference to the reference point around which the circle is formed), and was, during antiquity and the Middle Ages, the universal hypothesis about of the movement of the cosmos, in which the earth was at the center.

The most famous of the geocentrists is Claudius Ptolemy, whose ideas were a reference book for medieval astronomers, both Christian and Muslim. However, before him there were many other supporters of geocentrism, the great Aristotle among them.

In today’s article we will see what geocentrism consists of and what has been its trajectory in history.

What is geocentric theory?

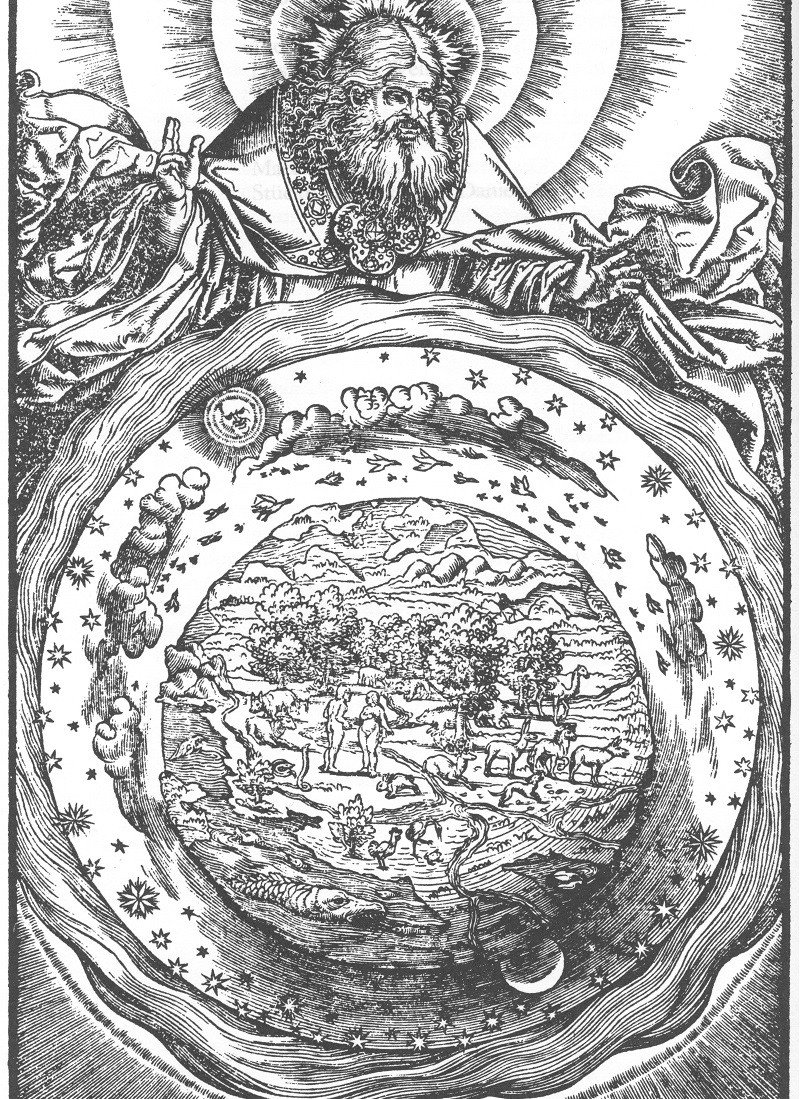

Since ancient times, human beings have believed themselves to be privileged and favored by the gods, which led to the postulation of the geocentric idea as the basis of the movement of the cosmos since Mesopotamia. This theory places the earth at the center of the universe, as the most important entity, since it contains divine creation

Over the centuries, and despite the fact that observable evidence cast doubt on this hypothesis, all peoples recognized it as a basic truth in their cosmogony. Let’s see below what this story has been.

The long history of geocentrism

One of the best-known authors on geocentrism is Claudius Ptolemy, an astrologer and mathematician from Alexandria in the 2nd century AD. In his best-known work, the Almagest (Arabic name that means “mathematical composition”), the scholar makes a compilation of Greek knowledge regarding the cosmos and its movements. Ptolemy also introduces a novelty: the curious theory of the movement of the stars on epicycles, which we will explain later.

But if Claudius Ptolemy collected previous knowledge about the movement of celestial bodies in his Almagest, this means that the geocentric theory had been accepted for centuries. In fact, The astrologers of ancient Babylon already considered the earth as the main axis of the universe Already in the Greek world, pre-Socratics such as Anaximander (6th century BC) affirmed that the earth was a cylinder suspended in the universe, around which other bodies “floated”. But while Anaximander and his colleagues believed that this “cylinder” represented the center, the Pythagoreans affirmed that the earth was not on the axis of the universe, but that it revolved around an invisible fire.

Can we consider that earth revolving around the “invisible fire” a glimpse of heliocentrism? Hardly. However, it is true that the heliocentric theory (that is, the one that places the sun, and not the earth, in the center) was already known in Greek times. Authors such as Aristarchus of Samos (4th century BC) and Heraclides of Pontus (4th century BC) maintained that it was the sun, and not the earth, the element around which bodies rotated.

These incipient heliocentric postulates had no force, in part, due to the great prestige that Aristotle, an eminent geocentrist, had in antiquity and the Middle Ages. In fact, thanks to him, Plato and Ptolemy, the geocentric theory spread beyond the ancient world and passed into the medieval centuries as the only accepted hypothesis, both in the European and Muslim worlds.

Reasonable doubts in the field of astronomy

The consolidation of geocentrism occurred despite the serious contradictions it entailed. And if the geocentric postulates are true, There were certain celestial movements that could not be clearly explained This, however, did not seem to pose any problem for the scholars, who “adapted” the observable movements to the theories, instead of the other way around.

For example, Ptolemy justified the movement of the so-called wandering stars (that is, the planets), through the already mentioned system of epicycles. According to this theory, widely accepted during late antiquity and during the Middle Ages, the Earth would remain fixed at the center of the universe, and the planets would move around it through deferential orbit. But not only that; At the same time, these bodies would rotate about points, the epicycles. The result would be a double movement with a spiral effect that would be, according to Ptolemy, the “natural movement” of the cosmos. By the way, in the film Ágora (2009), by Alejandro Amenábar, there is a scene in which one of Hypatia’s students illustrates this Ptolemaic idea very well.

The era of the scientific revolution

The “universal” acceptance of geocentric theories was motivated, in part, because It fit perfectly with the religious ideas of an earth created by God , around which the rest of the universe revolves. If the human being was the most excellent creature of this divine creation, the place where he lived must necessarily be in the center. There didn’t seem to be any discussion about it.

But in the 14th century, a revolution began that had a special impact on the British Isles, in the so-called “Oxford circle.” It is headed by illustrious thinkers such as Roger Bacon (1220-1292), Duns Scotus (d. 1308) and, above all, William of Ockham (1287-1347), the creator of the theory of “Ockham’s razor”, which It definitively separated the paths of faith and science and inaugurated a new era of scientific thought.

In line with this revolution, In the 15th century, a character appears who will be crucial for the change of mentality: Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543), a Polish Catholic clergyman who relaunched the heliocentric theory postulated in ancient times by Aristarchus of Samos and Heraclides of Pontus. Copernicus will establish the sun as the center around which the planets rotate, in what has been called heliocentric theory (from helios, “sun”).

Soon, encouraged by scientific discoveries (among which is the telescope, which will allow us to observe the stars up close), other illustrious figures such as Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) and, later, Isaac Newton (1643-1727), They will effusively join Copernican theories. The time of the geocentric theory was over; at least, officially. Today, it is still valid in some communities, despite its obvious expiration.