In the last century (and, especially, in the last decades) medical studies have allowed more advanced knowledge about diseases and how to treat them. In many cases, these experiments have concluded satisfactorily and have resulted in surprising solutions for the cure or, at least, for the mitigation of the symptoms of some diseases.

However, it is no less true that some of these experiments raise serious doubts about their ethical validity, such as the study in question, known as the “Tuskegee experiment.” This is the eternal question: Does the end justify the means used? Can we, then, reason the conduct of a controversial study with the maxim that the result is “well worth the sacrifice”?

In the case at hand, the human rights violations were especially serious. When the truth of the experiment was uncovered, the world raised its hands, and this allowed the green light to be given to a series of codes and institutions that guaranteed the observance of human rights in scientific experimentation. In today’s article, we talk about the Tuskegee experiment and its ethical and social consequences.

The Tuskegee experiment: when science plays with human beings

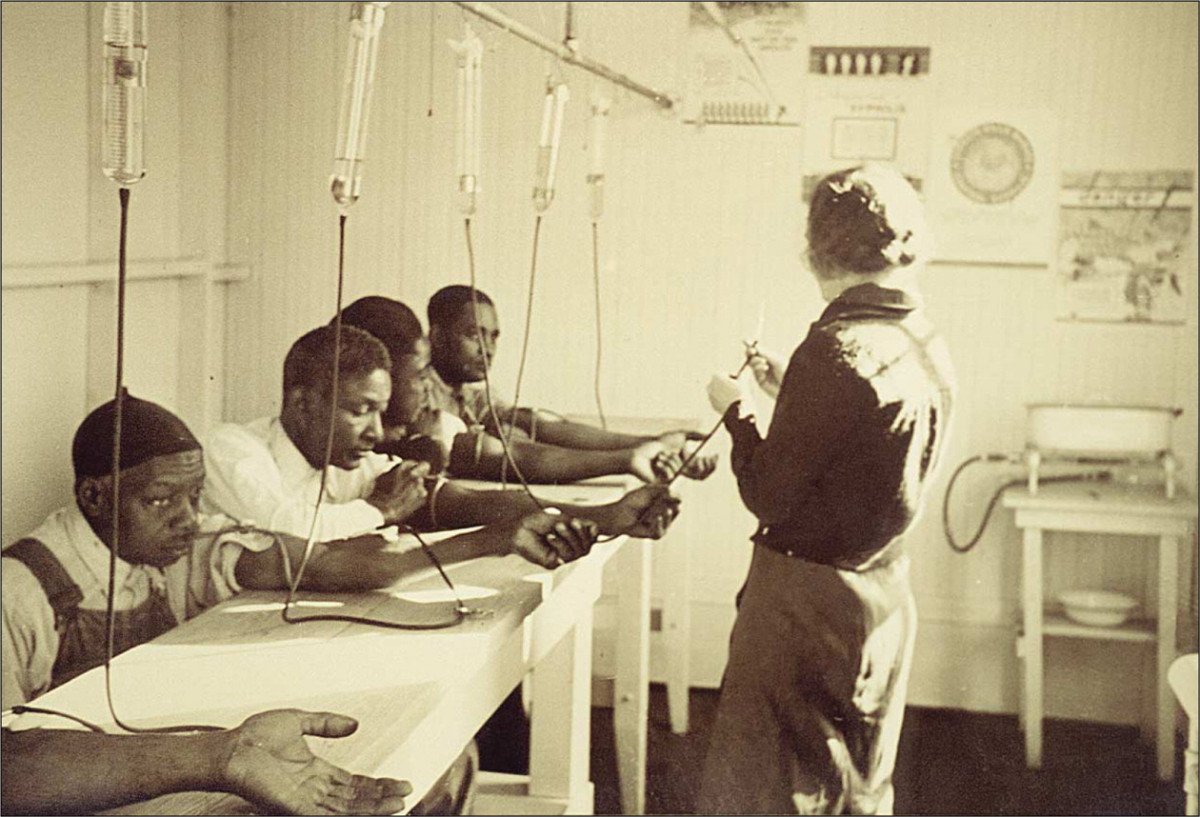

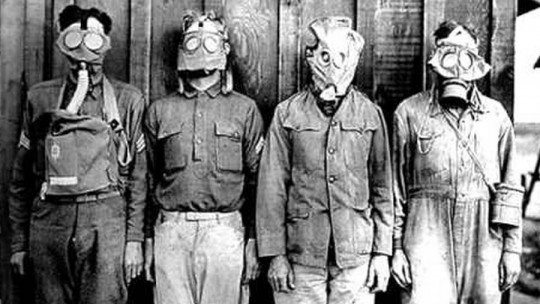

Before getting into the matter, let’s briefly situate the reader. We are in Tuskegee, Alabama (United States), in 1932. In those years, syphilis, one of the most feared venereal diseases, continued to ravage the population That year, the United States Public Health Service, together with the Tuskegee Institute, decided to undertake a study that would last no less than four decades and whose objective would be to monitor the progress of the health of 600 men, all African-American and practically illiterate. Only 201 individuals are healthy; the rest are infected by the bacteria Treponema Pallidum, which causes syphilis.

Currently, it is a little-heard of disease (although, unfortunately, it is still active in the world), but throughout the history of humanity it has been one of its worst nightmares. Syphilis is a bacterial infection that is contracted through contact with the genitals of the sick person, although it can also be spread through the lips and anus. It is logical to think that sexual activity is the most favorable means by which syphilis enters the body, which is why for millennia it has decimated the population, especially individuals who frequent brothels or have multiple partners.

Like all diseases, syphilis can be more or less severe. In extreme cases, it can lead to death, especially if not treated properly. In this sense, Traditional medicine prescribed doses of mercury, usually in the form of an ointment applied to the skin ulcers that the disease left on the body As can be deduced, mercury, a highly toxic substance, did not help much in curing the patient.

In the 1940s, penicillin, a powerful antibiotic, began to be used, so syphilis began to subside. However, as we will see below, the people who were used without any scruples in the Tuskegee experiment did not receive any guarantee of cure.

Rather, The objective was for the disease to occur naturally, in order to observe, in this way, the body’s natural resistance A real attack on ethics, of course, especially considering that none of the 600 volunteers had knowledge of the truth.

An experiment lacking all ethics

Initially, the mission of the experiment was to monitor the natural progression of the disease to develop effective treatments. However, three things stand out: one, that the signed consent of any of the volunteers was not required; two, that they were not even informed that they were being the protagonists of a study, nor that they were positive; three, that they were “recruited” with promises of free general medical treatment and food; and four, that all, without exception, were poor and practically illiterate African Americans, which makes evident the racism and elitism hidden behind the experiment.

More than ten years after starting the experiment, when penicillin emerged as an effective tool to combat syphilis, no one informed these people of the news The volunteers continued without being treated, and the disease continued to occur naturally, with the consequences that this entailed on their health and life. The scientists’ intention was to study syphilis and its effect on the body to its ultimate consequences; Apparently, the death of 600 people was not inconvenient for their objectives.

These consequences were truly frightening. More than 120 people died as a result of the disease or related causes. On the other hand, the lack of effective treatment had caused the infection in forty of the patients’ wives, which also led to several children born later coming into the world carrying the disease.

Finally, in the 1970s, the chilling experiment was leaked to the press and those responsible had to stop the process But it was too late; many families had been destroyed for the “benefit” of science.

The Tuskegee case and the beginnings of bioethics

The person who leaked the experiment to the press in 1972 was Peter Buxtun (1937), an employee of the United States Public Health Service, who had been trying to stop the macabre study for eight years. Although the successive results had been published (up to thirteen times) in medical journals, the majority of the population was unaware of the existence of the experiment.

Thus, the revelation of the truth about the Tuskegee case was a real scandal. The experiment was immediately stopped, and the survivors and families of those affected were compensated. In 1978, the Belmont Report came to light, a document on which the main bioethical codes are based and the first official guarantee of scientific ethics regarding experiments with humans

Those responsible for the study argued that they were due to scientific interest, that is, to observe how syphilis develops. However, although this could be excused to a certain extent when there were no effective treatments, after the appearance of penicillin the exclusion of volunteers from treatment had no justification. Neither did the fact that he had deceived all these people for the “benefit” of science. At least, if something “positive” can be drawn from this chilling event, it is that it laid the foundations for global bioethics.