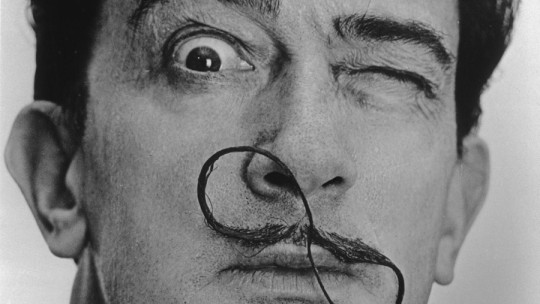

Few people are unaware of the fact that the father of psychoanalysis was Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), who, as early as 1899, published his revolutionary work The Interpretation of Dreams, considered the starting point of psychoanalytic technique. After the discovery of the subconscious, nothing would be the same again

Neither did the world of art, which began to be nourished by the precepts of Freud and his disciples and resulted in currents inspired indisputably by Freudian theories, such as surrealism or Dadaism. It is indisputable, then, that André Breton’s surrealists, through their automatic system (which encouraged the unconscious to be left free during artistic creation) followed Freud’s ideas regarding the need for disinhibition of the mind, flooded with traumas and of complexes.

And, although the famous Austrian psychiatrist became interested very early in the relationship that existed between psychoanalysis and art, the curious thing about the case is that he never understood the surrealist movement nor did he make any effort to attend to Breton’s efforts to capture it for his group.

What relationship exists between psychoanalysis and art? Are Freud’s theories correct, according to which all works can be interpreted psychoanalytically? What did the psychiatrist’s work mean for art in general (and not just for the surrealists)? In the following lines we try to tell you.

The relationship between psychoanalysis and art. Freud and his psychic vision of art

At the beginning of the 20th century, around 1914, Sigmund Freud published a series of studies in which he examined the relationship between the psyche and the work of art One of these writings is his study of Michelangelo’s Moses, as well as his analysis of Leonardo’s production and personality.

In a letter to his wife Marta, dated 1912, Freud, who was on one of his frequent stays in Rome, comments that he longs to unravel the mysteries of Moses, a sculpture that exerts a strange spell on him. Through an exhaustive contemplation of the work, Freud concludes that Michelangelo represented the prophet just after, upon coming down from Sinai and seeing his people in full pagan worship, he was overcome with anger and, in an act of supreme control, restrained himself from destroying the Tables of the Law.

That is to say, the Florentine genius renounces representing it at the moment of his greatest anger, when he throws the Tablets at the rebellious people, to offer it to the viewer in an attitude very different from that customary in the history of art.

The work of art as a reflection of the artist’s psyche

Although on this occasion the Viennese does not strictly delve into psychoanalytic fields, he is expressing a vision of the work of art from a psychic point of view, that is, based on what the artist intended to communicate. Many authors have seen in these studies by Freud the embryo from which it will develop. a current that interprets artistic creations with respect to the psyche and the most intimate personality of the artist

In the magnificent interview that the Spanish Society of Psychoanalysis conducted with the psychoanalyst Anna Romagosa (see bibliography) she picks up this idea when she comments that, indeed, for Freud there was a relationship between the unconscious and art, in the same way that there is a connection between that and the dreams.

Romagosa also insists that, after the work of the Viennese psychoanalyst, others picked up the baton: the so-called Kleinian school (after its initiator, Melanie Klein) maintained that art facilitated the release of internal conflicts and traumas carried over from childhood.

In other words, it represented a reparation. On the other hand, after the Klein school, the psychoanalyst Donald Meltzer (1922-2004) added to all this the concept of aesthetics, through the idea of aesthetic conflict, based on the impact that the complex beauty of what surrounds it produces on the newborn

The work of art as a dream experience

Wilfred R. Bion (1897-1979), who had drawn on the theories of Freud and Melanie Klein about the connection between art and the unconscious, proposed a relationship between the experience of human emotions and creation. This idea connected directly with the work of some surrealists, who expressed an entire dream world through images

Regarding this, the work of René Magritte (1898-1967) is usually indicated as an example, whose paintings of everyday objects linked together without any apparent logic seem to refer to the world of dreams. However, the Belgian painter never wanted to know anything about psychoanalysis; In fact, he categorically rejected the idea that there was a “hidden” or “symbolic” meaning in his paintings.

As he himself says, and as Anna Romagosa and Antònia Grimalt record in their article Magritte and psychoanalysis (see bibliography), the artist did not know why he painted a painting, and “he didn’t want to know either.” It is evident that Psychoanalysis tends to interpret reality as a mask of a hidden meaning, as it is a reflection of traumas and conflicts of the psyche But can this idea be transferred to art?

Is it logical to reduce art to a manifestation of the artist’s subconscious?

This is the big question, the one that should be suggested in every line of this article. After the appearance of Freudian theories of the relationship between art and psychoanalysis, an important current of art historians was generated who sought to see in the works manifestations of the psyche of their author.

There are very curious cases, such as Correggio’s Noli me tangere, where the garden hoe was interpreted as a phallic symbol On the other hand, Oskar Pfister (1873-1956), a disciple of Freud and interested in his psychoanalytic study of Da Vinci, “clearly” saw a vulture in the shape drawn by the Virgin’s cloak in Leonardo’s work The Virgin with the Child and Saint Anne, which was quickly connected with the anecdote expressed by the painter that, in his childhood, a vulture suddenly approached him, a memory that Freud interpreted as a desire for “passive fellatio.”

Aside from the fact that the theory already seems, per se, quite far-fetched, we must not forget that both Correggio’s and Da Vinci’s paintings also involved their respective workshops, so it does not seem very plausible that there is any such an evident trace of the “unconscious drives” of the artists.

Currently, the psychoanalytic interpretation of works of art is taken from a certain perspective Without the intention of rejecting it completely, the new currents prefer to see artistic creations as a mixture of factors, not all linked to the hidden desires and fears of their author.