After the death of Siddharta Gautama, the Buddha, in 483 BC, Buddhism began to spread throughout India and the rest of Asia. Soon, and despite the fact that the first manifestations of Buddhist art were aniconic (that is, they did not depict Buddha as a man, but rather expressed him through symbols), the figure of the master deeply inspired Asian art, and his influence reached until the distant islands of Japan.

Buddhist art is by no means a homogeneous art Although there are certain guidelines, generally respected by all expressions of this type of art, we also find significant differences between the various schools, the result of a specific context and specific cultural influences.

In today’s article, we briefly review what Buddhist art is, its characteristics and origins, as well as the evolution it underwent from its beginnings, shortly after the death of Buddha, until its consolidation.

What is Buddhist art and what are its origins?

After the death of Buddha, his teaching or dharma spread with dizzying speed Let us remember that the founder of Buddhism had been a rich aristocrat from what is now Nepal and that, deeply impressed by the miseries of life (illness, hunger, death) he decided to renounce his previous life and follow the path of meditation.

After his enlightenment (hence his nickname, the Buddha, “the Awakened One”) dedicated himself to disseminating his teachings, which were based on choosing an intermediate path between wealth and the harshest asceticism, in order to eliminate suffering. Not long after his death, we already found the first manifestations of art inspired by his figure. But let’s look more closely at what these first testimonies of Buddhist art are.

The aniconic period

Before the 1st century BC, Buddhist art was eminently aniconic, that is, it refused to represent Buddha in human form. The artists therefore developed a very original art, based on the symbology that tradition had granted to the master : the wheel, which referred to the dharmachakra or the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism; the Bodhi tree, under which, according to tradition, enlightenment came (and which has clear parallels with the Tree of Life represented in many cultures); or the lotus flower, symbol of Buddha’s immaculate purity, because, like the lotus, it rises above the mud.

Other symbols related to Buddha that abound in this first aniconic period are the empty throne with the footprints at its feet, representing emptiness, since the master, after his Enlightenment, stops conventionally “existing.” In these cases, we would be facing the representation of the Not-Buddha.

The first great Buddhist art: the Mauryan empire

Ashoka is the first great ruler of India, a descendant of Chandragupta, the leader who managed to confront the Greeks of Alexander the Great who, in their wanderings through Asia, had managed to reach the Indian subcontinent. Ashoka was known as Ashoka the big one for the great splendor that his kingdom achieved during his mandate, a kingdom that he managed to unify culturally and politically under the impulse of Buddhism, of which he was a great follower.

It is in Ashoka’s Mauryan empire that we find notable artistic manifestations of the Buddhist religion ; among them, the well-known stupas, originally from India but later, with the spread of Buddhism, spread throughout the rest of Asia under other names.

These are monuments of a sacred nature, apparently coming from ancient burial mounds and which, according to tradition, would have housed the ashes of the Buddha himself and other sacred figures of Buddhism.

Its morphology became more complicated over time in order to accommodate the huge number of pilgrims who came, and they became authentic architectural monuments. In general, they have a square base and a hemispherical body, on which a palisade was built that would symbolize the altar. Access to the interior is through four doors, located in the wall that surrounds the monument, which usually present notable reliefs.

On the other hand, characteristic of this first Buddhist art promulgated by Ashoka are the monolithic pillars, such as the famous Sarnath Capital, called the Ashoka Capital, although, in reality, there are many capitals on pillars that this monarch ordered to be erected in the north of India. Sarnath is especially important in Buddhism because it was there that Buddha first preached to the faithful

Towards the human representation of Buddha

It is only from the 1st century AD that we begin to find anthropomorphic representations of Buddha. This is a curious phenomenon of which scholars have tried to find the origin: why does an art that resisted capturing the master in human form finally end up doing so? What are the factors involved?

In one of his magnificent articles on Buddhist art, the art historian Ramon Muñoz López (see bibliography) specifies a series of circumstances that could have facilitated the appearance of the anthropomorphic sculptures of Buddha. First, the split of Buddhism into several schools, among which is the Mahayana o Large Vehicle , a current that appeared in the middle of the 2nd century AD that is much more in favor of approaching the faithful, that is, the humble ordinary people. The Mahayana school affirms that everyone is capable of achieving enlightenment, so the figure of Buddha is humanized to bring him closer to the common people.

On the other hand, let us remember that the Greeks of Alexander the Great had been in northern India. It may seem like a somewhat faded factor, but that is not the case. After the death of the conqueror and the division of his empire, A small Hellenic state called Bactria was founded, which powerfully influenced the culture of the area This Greco-Bactrian empire was located right in the center of Asia and had a border, precisely, with the Mauryan empire of northern India. And it is in one of those regions, Gandhara (in present-day Pakistan) where a completely new art begins to develop.

In Gandhara the presence of Hellenic art causes a strong anthropomorphization that reaches the figure of Buddha.

So, sculptures that represent the master begin to appear, with a marked Greek influence Some scholars have even gone so far as to compare the graceful and beautiful figures with the Greek Apollos and, even with a certain reservation, they are right. Many of these Greco-Buddhist sculptures express a subtle contrapposto and curly hair that is very reminiscent of the Olympic gods. It is an amazing cultural fusion and enormous beauty.

Less naturalistic is the representation of Buddha in the Mathura area, also in northern India, which, although equally influenced by Greco-Buddhist art, soon acquires its own characteristics.

In Mathura, the effigies of Buddha are much more idealized and present a profound hieraticism and a marked frontality that remind us of Egyptian sculptures. At the basis of this geometric idealization of forms and the majesty of figures is the concept that Buddha, as the Enlightened One, has transcended humanity and is, in reality, more than a man.

The consolidation of the representation of Buddha

During the Kusana period in India (2nd and 3rd centuries AD) there was a standardization of the characteristics that any anthropomorphic representation of Buddha should have. Thus, and despite the stylistic varieties of each region, the 114 laksanas or characteristics that any representation must have, of which 32 are basic and the rest are optional. Here we offer some of these laksanas mandatory, collected from the article by Muñoz López:

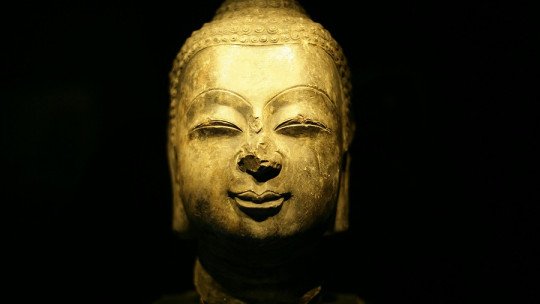

One of the schools where anthropomorphic sculpture of Buddha proliferated is the so-called Gupta School (4th-6th centuries), which in many aspects is the heir of that of Mathura. However, one of its innovations is that it goes beyond the “archaic” and hieratic style and promulgates a very refined art that elevates geometric volume to artistic expression. A clear and beautiful example is the Buddha Head preserved in the Sarnath Museum, of astonishing purity of form, and which shows the master concentrated, with his gaze lowered (one of the laksanas basics). To highlight the profuse network of spirals that represents her hair and the delicate elongation of her ears.

Conclusions

We cannot summarize the entire evolution of Buddhist art in such a short article. We have limited ourselves to offering some basic characteristics and a few glimpses of the historical and cultural context that saw its birth.

From India, the cradle of Buddhism, his art spread, mainly through the Silk Road, to other regions of Asia, some as far away as China or Japan. This Buddhist art, let’s say, from the north, would show some differences with respect to the Buddhist art of the south, that is, the one we find in Southeast Asia.

On the other hand, there is an essential period to understand Buddhist art: the moment in which we move from an aniconic creation, based on symbols and concepts, to the embodiment of Buddha as a human being. In this sense, Buddhist art owes a lot to factors such as the “popularization” of Buddha’s philosophy, which brought the teaching closer to the faithful through the Mahayana; and, on the other hand, to the enormous influence of Greek art from the Bactria region.