All, absolutely all cultures have developed a specific image of the afterlife. The idea of nothingness after death is a very modern concept; During the history of humanity, each community has generated a particular vision of life postmortemsome of them very elaborate and often presenting various points in common.

Today’s article is intended to be a brief analysis of the vision of the afterlife of six civilizations with religions : Greek culture, Egyptian culture, Christian culture, Buddhism, Viking culture and the ancient Aztec religion. We have dedicated a section to each of them, although we will also establish a certain comparison that allows us to glimpse what aspects they have in common. Keep reading if you are interested in the topic.

How do the various religions conceive the afterlife?

Although we have commented in the introduction that each and every culture considers a specific reality after death, it is obvious that this vision varies depending on the society that projects these ideas. There are religions that affirm the existence of a trial after death which will determine if the deceased is worthy of entering the kingdom of perpetual happiness or if, on the contrary, he deserves punishment for all eternity.

On the other hand, we find other cultures, such as the Aztec, that “classify” the deceased according to the type of death and do not pay special attention to the way in which they have lived their earthly existence. Finally, other belief systems, such as those that make up Buddhism, focus on a state of spirit rather than a specific place, as we will see.

Greece and the abode of shadows

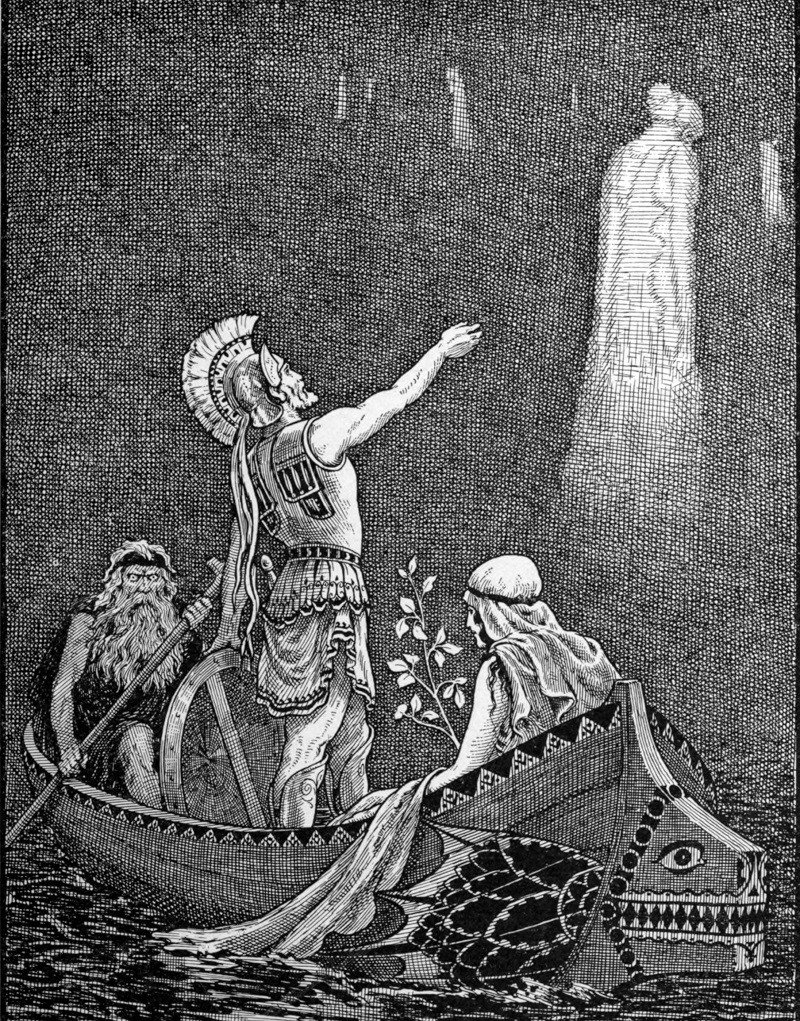

The ancient Greeks, at least until classical times, imagined the realm of the dead as a shadowy place where the souls of the deceased lived as shadows According to Homer, these shadows had no capacity for discernment, and wandered through Hades (the name of his abode) bewildered and aimless.

The outlook was, as we can see, very unflattering. Little by little, an authentic geography of Hades was formed, an authentic underground world that was accessed through the Acheron, a real river that was hidden behind some rocks and that, according to the Greeks, was the entrance to Hades. Waiting on that river was Charon, the boatman, who had the mission of transporting the deceased to the kingdom of the dead in his boat. This boatman had to be paid with an obol (a coin), so the relatives of the deceased had the custom of depositing them in the eyes or mouth of the deceased.

We can’t entertain ourselves here the description of the geography of Greek Hades Yes, we will mention the origin of the name; Hades was the god of the underworld, the lord of the dead, who had received his kingdom, according to tradition, from a game of chance he played with his brothers Zeus and Poseidon. The latter were given the sky and the seas, respectively, while Hades had to settle for the shadowy world beyond the grave, which, according to the oldest texts, was not found underground, but beyond the Ocean.

Hades’ wife is Persephone, the Kore of the mysterious rites, the Roman Proserpina. Hades is her uncle, while the girl is the daughter of Demeter, sister of the gods and patron of the crops and fertility of the earth. Infatuated with her niece, Hades kidnaps her and takes her to her infernal kingdom, from where the young woman can only leave each spring, when the fields bloom again. However, with the arrival of autumn, she is forced to return to her husband again.

This ancient myth establishes an obvious relationship between death and life, a relationship that, on the other hand, was quite common among ancient people. Persephone would therefore be the seed that, buried in the earth (the homeland of the dead), makes life rise again and thus nourishes the world. Living and dead would therefore be indissolubly and eternally connected.

In the time of Plato (5th century BC) the concept of the afterlife changed significantly In his work Gorgias, the philosopher exposes the theory of postmortem reward, according to which the virtuous and the heroes (that is, those who participate in the idea of the Good) will find eternal happiness in the Elysian Fields, surrounded by pleasure and beauty.. On the other hand, the wicked who reject the Good and the Beautiful will be condemned to Tartarus, the gloomy region of Hades that waters the Phlegethon, the river of fire. A clear parallel is thus established between the Platonic concept of fire as a purifying entity and the idea that would later prevail in Christianity.

Egypt and eternal identity

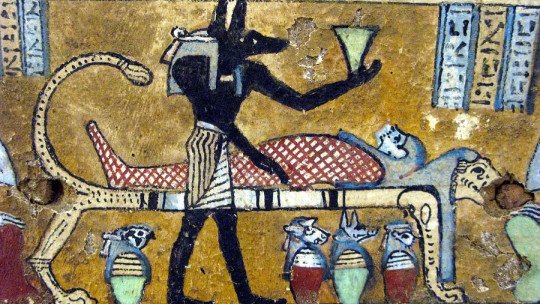

This concept of “classification” of souls is also found in mythology. postmortem of the ancient Egyptians, well, After death, the deceased witnesses the weighing of his heart, the only organ that has not been removed with mummification Thus, the viscera is deposited in the scales of Maat, Justice, by the jackal-god Anubis. Osiris, the dead and resurrected and lord of the underworld, presides over the event.

In the saucer opposite to the heart, Anubis places the feather of Maat, light and accurate, which will determine the weight of the deceased’s actions. If the heart weighs more than the feather, it will mean that the evil of the dead person is excessive, so he will not be allowed access to eternal life. In that case, Ammyt, the Great Devourer, swallows the deceased and everything ends here.

There are obvious parallels between the monster Ammyt and the Leviathan of the Judeo-Christian tradition , in turn charged with devouring impious souls. We find numerous representations of this being in medieval church frescoes, often represented as a monster with a huge mouth and ferocious teeth, ready to devour the soul of the deceased.

In the Egyptian case, this ending was especially tragic. In Egyptian culture, unlike Greek culture (in which, remember, the deceased was nothing more than a nameless shadow), the soul of the deceased continues to maintain its identity In fact, the main purpose of the mummification rite is to keep the form of the dead “intact”, so that, in this way, its Ba and his ka (two of the spiritual parts of which the human being is made up) are able to recognize it and thus reunite what had been scattered with death. That is to say, for the Egyptians, death is a moment of “small” chaos, in which the components disintegrate; To guarantee eternal life, it is necessary, therefore, to reunite what has been separated and to reshape the identity of the deceased, full and complete.

This is inevitably reminiscent of Osiris’s death at the hands of his jealous brother Seth and his subsequent dismemberment. The different parts of the god’s body were distributed throughout the earth, and Isis, her sister and wife, was in charge of recovering them to put back together the body of her husband. Thus, Osiris, the dead and resurrected (after three days, by the way, in a clear parallel with Jesus) becomes the lord of the dead and guarantor of eternal life.

Punishment and reward in the Judeo-Christian tradition

Another common feature that the Egyptian concept of death has with Christianity is the idea of preserving the body after death Well, even though Christians do not mummify their dead, they are prohibited from cremating them. The idea is that you cannot intervene in the destruction of the flesh, since it will be resurrected on the Day of Last Judgment, at the second coming of Christ.

Initially, the Last Judgment was spoken of as the moment when the world would end and souls would be judged collectively based on their actions. However, this end, prophesied in the thousandth year of the Savior’s coming into the world, did not come. Nor was there any end of the world in the year 1033, the year that marked the thousandth anniversary of the death and resurrection of Jesus. Consequently, the concept of salvation began to change: not only was there a collective judgment at the end of time, but, after individual death, the deceased would be judged personally. In this case, instead of Anubis, the iconography presents the archangel Michael holding the scales and fighting against the demon, who tries to unbalance it to take the soul.

In the Christian case we also find, therefore, a “classification” of souls based on their acts in life To the traditional places of Paradise and Hell, in the 13th century, the concept of Purgatory was added, an indefinite place where “intermediate” souls (that is, those who were neither evil nor virtuous) “purged” their pending sins. of definitive access to heaven.

The case of Purgatory is curious, since its invention is due, in a certain way, to the evolution of society in the Late Middle Ages. The 12th and 13th centuries are the centuries of the rise of cities and commerce and the rise of the bourgeoisie. Monetary lending is no longer a “Jewish thing,” and Christian bankers are beginning to do business with interest. In other words, they make a profit from time, since the more time passes, the more interest the client to whom the money has been lent will have to pay. Therefore, the change in mentality is evident: time is no longer the exclusive property of God, but also belongs to man. It is the time when Christians pay the Church to shorten years of Purgatory for their loved ones. God no longer has the last word, therefore, in eternal punishment.

The Viking sagas and the final resting place of warriors

The Viking society, as eminently warrior-oriented, gave special importance to death in heroic combat Those who had fallen honorably on the battlefield were raised by the Valkyries, beautiful women who rode winged steeds and who took them to Asgard, the home of the gods. There, in the “Hall of the Fallen” (the famous Valhalla), these warriors enjoyed a life of pleasure for all eternity, in the company of Odin, the lord of the gods.

In Viking mythology about the afterlife we find a concept similar to that of Aztec mythology: that of “classifying” the dead by their type of death rather than by their actions, although, in the Viking case, these were also taken into consideration.. So, Those who died due to natural death accessed another place, the Bilskimir, run in this case by Thor , the lord of thunder. Of course, it could only be accessed if the deceased had nobility of heart.

Finally, there was a third place, Helheim, the territory of Hela, the chilling goddess of death, daughter of the wicked Loki. It was an inhospitable and desolate place, like the Greek Tartarus, where the souls of those who had been truly evil rotted. Helheim (most likely root for the English word hell), was located in the depths of Yggdrasil, the cosmic tree, and, similar to what happened with Cerberus (the three-headed dog that guarded Hades) , was protected by Garm, a monstrous dog. Helheim was a truly terrifying place, but, unlike Greek Tartarus (which we remember was bathed by a river of fire) and Christian hell, Viking punishment was made up of masses and masses of ice and icy storms, which proves, a once again, that the concept of the afterlife adapts to the environment of the society that creates it.

The different Aztec “types of death”

Mictlán was the land of the dead in the ancient Aztec culture It was run by Mictlantecuhtli, the terrible lord of death, and his wife Mictecacíhuatl. Mictlán was a place located underground that was made up of no less than nine stories deep, full of spiders, scorpions, centipedes and nocturnal birds. And if the kingdom was terrible, its lord was no less so; Mictlantecuhtli was represented as a skeleton whose skull was overflowing with teeth, in a sinister eternal smile. His hair was matted and his eyes shone in the middle of the darkness of Mictlán.

Curiously similar to the Greek Hades, the kingdom of the dead was watered by several rivers that ran underground; The first of them represented the first test that the deceased had to pass, for which it was essential to be accompanied by a guide dog. For this reason, it was common for the deceased to be buried with the corpses of this animal, as well as with numerous amulets that were supposed to help the deceased overcome all the trials that awaited him, which were not few. It is curious to note that The rate of putrefaction of the corpse was indicative of the speed with which the soul was passing the tests : The faster the body was consumed, the luckier the deceased was having in the afterlife.

The Aztec underworld is, therefore, a kind of personal improvement, which culminates in an individual judgment of which the deceased is his own judge, since he must appeal to his conscience. However, ultimately, the geography of Mictlán was more dictated by the type of death the person had suffered. Thus, the heroes were destined to Tonatiuhichan, a place next to the sun to which women who had died from childbirth were also sent, also considered heroines. On the other hand, there was one last place: Tlalocan, reserved for those who died due to drowning or lightning strikes (since it was the home of the god Tláloc, lord of the elements).

Buddhism and personal salvation

Throughout this exposition, the case of Buddhism stands out clearly. Unlike other religions, this Eastern philosophy denies individuality ; The soul does not have its own identity and, in reality, authentic salvation will come from the liberation of the samsara or eternal cycle of reincarnations.

Buddhism considers death to be a mere transition from one existence to another, for whose preparation meditation is essential. Through it, the self dissolves and becomes fully aware of the non-permanence and insubstantiality of all things. The liberation (the famous nirvana) is, therefore, the annulment of existence as such and, therefore, of the self, of individual identity. He nirvana (literally, from the Sanskrit “to cool by blowing”, that is, to cool desire) is nothing other than a state of enlightenment, not a place, unlike other religions.

The fact that Buddhism does not recognize a physical and concrete postmortem place makes sense if we consider that, for this philosophy, the soul is an indefinite element, not a full identity as it was in the case of Ancient Egypt. Thus, it is subjected to a cycle of reincarnations, the endless wheel of samsara, depending on the vital energy that we accumulate, the karmaand its definitive liberation will only be possible when we enter the state of nirvana: the understanding that, in reality, nothing remains and nothing is.